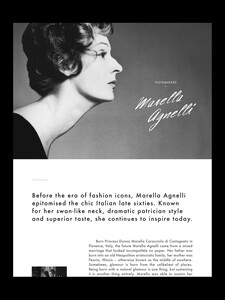

Can you introduce yourself?

My name is Benjamin Grillon. I am an artistic director. I founded my studio 6 years ago. I lived in London for 17 years and returned to Paris a few months ago.

I am introducing myself as an artistic director because I find the term “creative director” a bit pompous and abstract. “Artistic director” is already an abstract term for many people; the meaning differs greatly depending on the context of the job. To put it in perspective, I often say that I work mainly in the fields of fashion, art, and culture.

What is your current state of mind on January 4, 2023?

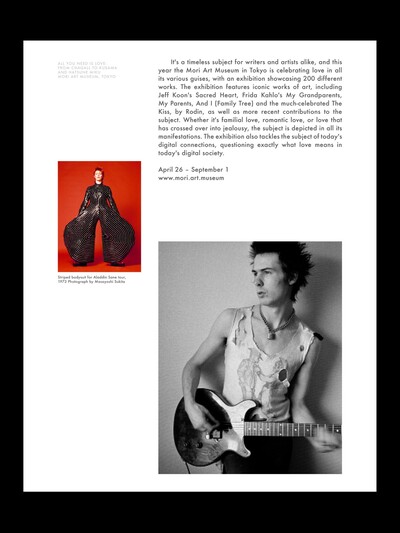

I am a pretty positive person in general, and I find that, at the beginning of the year, there is always this blank slate effect, which is quite exciting. You can dream of new projects and give yourself a new impetus. I have a lot of projects in the works at the moment, namely, the launch of a magazine/book collection called Colour Journal. I have been working on it for several years; it will go hand in hand with the launch of a publishing house. Right now, there’s a discussion happening with a potential client about taking over a magazine. So the start of the year is rather promising.

Icicle - FW24

How did you get into graphic design and artistic direction?

I didn’t go to London for graphic design but actually for music: I played in a band (Lust, a post-rock band, then Scanners, an English band I joined later on). I was playing bass and singing (laughing). I ended up in London a bit by chance. I wanted to go abroad to learn English and also for music. It was either New York or London. I sent my portfolio to agencies abroad, but New York was too complicated because I didn’t have a green card… an agency in London accepted me, and that was it!

I knew I wanted to do design since junior high school, but more product design, maybe. I think it’s because of the ’90s and the rise of designers like Starck, who got a lot of media coverage. I must have been fourteen, and I already wanted to do design, but I saw design as something quite broad. I asked my parents if I could go to the open houses of the applied arts schools in Paris. I did my high school internship in a product/spatial design agency. After that, it was music and album covers that got me a bit more interested in graphic design. I had an appetite for images; I read my mother’s issues of Vogue and Elle when I was a teenager. I think that’s what opened me up to image, fashion, and artistic direction in general.

I am purely self-taught. I got kicked out of three high schools, and my parents didn’t want me to study for an applied arts baccalaureate. They thought it was strange that from such a young age I knew exactly what I wanted to do and they wondered if it was just a phase. They must have been afraid that I wouldn’t be able to turn back if I ever changed my mind. It so happened that I did not change my mind. Since I was kicked out of three high schools, I was never able to get into the foundation programme for applied arts, so I opted for Beaux-Arts because acceptance was based on the results of an entrance exam. I passed the exam: I went to Beaux-Arts and stayed there for six months. I did not like it at all. I went off to record an album with my band and never went back to class. I was fortunate to have understanding parents. I explained to them that there was no point in paying for five years of studies at Beaux-Arts, that it would be more productive to buy me a Mac so I could learn everything on my own. They paid for my Mac and financed a year of “self-study” for me.

Tutorials didn’t exist back then. I had a super computer-savvy friend who taught me some technical things. Because I was making music, I started out by making album covers, flyers, and posters for my band. Then, it was for all the bands in the local scene, and after that, the national scene, then the international scene… I was quickly drawn to an English label from Sheffield called Warp and to The Designers Republic, the label’s official design agency that did everything for them: the album covers, the identity. The moment I arrived in London coincided with the departure of Michael Place, one of the studio’s leading designers, who had set up his studio, Build, in London. I had the fortune to meet him and to collaborate with him on two or three projects. When it came to graphic design, though, electronic music was not very closely linked with the music I was making.

Sketch by Benjamin Grillon

How did you continue to develop your creativity and refine your tastes?

I think that the emergence of the digital defined, in a way, the Designers Republic aesthetic. I pretty quickly moved away from that to try and create a style that was a bit more timeless. There are quite a few visuals from that era that have not aged too well. And I think that what I’m looking for is a certain sense of timelessness. That often requires a more minimal approach.

In concrete terms, how did your career in London start?

So it was in 2005 with the boom of the internet and e-commerce. I was working for an agency that specialised in branding, graphic identity, and websites. For example, we were creating the Agent Provocateur site, which had just been founded. It was Joseph Corré, the son of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, who had that anti-establishment approach, which he must have inherited from his parents. We thought about the site the way we would think about a campaign today: every season, we completely redesigned it – e-commerce sites weren’t built the same way then as they are now. Today, sites are just shells. What makes the identity of the site is the content: the artistic direction of the image or film on the homepage. But at the time, image was not as important; it was more the design of the site that conveyed an aesthetic.

And UX guidelines were less present at the time.

The buttons were not all the same, and each had its own design.

Each season, Agent Provocateur had a different theme. One season, the theme would be the circus and in another, it would be film noir, for example. The entire collection was based on the given theme, and we completely redesigned the site every six months. I started to discover the Swiss approach to graphic design: the grid system and branding. This let me hone a more minimal approach. That’s what I learned by doing graphic charters and graphic identity. This Swiss school of thought, the idea of developing a system and applying it in different ways.

And when did you make the switch to doing more artistic direction and photography?

My career path has been very unconventional. In my generation, artistic directors for fashion all followed the same trajectory: they were interns at a cool magazine like Dazed & Confused or i-D, then gradually became artistic directors and then creative directors. Personally, I have never worked at a fashion magazine. Instead, I multiplied my agency experiences in London to learn a bit of everything and discover a lot of different disciplines. Web design, graphic identity… I even had the chance to work for Samsung’s research and development laboratory in London. That was just before the iPad came out. Samsung had the same technology as Apple, but they didn’t bet on portability. They bet on something they called the Surface. The idea was to revolutionise the home computer and to have a touch-screen table instead of a screen, keyboard, and mouse. I ended up working for nine months on the graphic interface for the prototype. And that’s what indirectly led me to fashion. You would have thought that it would take me away from fashion because it was really tech, but a few months later, the iPad came out, and I was contacted by a studio that had just developed the first independent magazine for the iPad, which was called Post. It is a very small agency that was set up by a former artistic director from Dazed & Confused, who saw the opportunity to bring into being the digital magazine, the magazine 2.0. The first customer was Gucci, who asked them to make a digital magazine for the iPad. And since none of the artistic directors working in fashion at the time had any technical knowledge as far as how to create a magazine for an iPad (when iPads first came out, magazines were simple PDFs that could be viewed on an iPad), my experience became my added value. So I came in with an aesthetic that was minimal, timeless, and rather luxury-oriented, that was well-suited to the fashion world. Plus, I brought technical knowledge. And that’s how I came to be the artistic director for Gucci’s magazine.

Gucci - Digital Magazine

Gucci - Digital Magazine

Gucci - Digital Magazine

What have been the other turning points for you? When did you become independent? And when did you get your studio?

The switch was the next step when Hermès decided to breathe new life into their brand magazine, Le Monde d’Hermès, which they’ve been publishing for over 30 years. It had been the same duo of artistic director and editor for years. I think the artistic director had been doing it for over 20 years. He had just retired, and they were hiring a new editor-in-chief who was looking for an art director, so that person, I believe, was seeing all the artistic directors in Paris at the time. I imagine that to escape the pressure surrounding that choice, he wanted to go see what was happening abroad, and what made the difference was that Hermès had the desire to create editorial content beyond the magazine, a bridge between the magazine and their website. Our experience with Gucci’s digital magazine was undoubtedly an advantage compared to artistic directors who had a more traditional, print-only approach. That’s what allowed me to make the change; right at that moment, I had left the agency I worked for to set up my studio. For the first time, I was no longer in the background; my name was at the top of the poster. The redesign of the Hermès magazine was a project that brought me a lot of exposure, and it was under my own name, not through an agency.

Hermès - Brand Magazine

When you look back, is there anything you would have done differently

Yes and no, because we are always the product of our own experiences. Maybe if I had known more about the industry and how things work at a younger age, I would have gone straight for an internship at a fashion magazine and started doing fashion much earlier. Would I have gotten to where I am now? Maybe not, since I am the product of this convoluted path. When I look back on things now, I would say that this journey has made me a multidisciplinary artistic director: I can design an e-commerce site as much as I can design an app, a font, a logo, a book layout… That makes me different from artistic directors, who maybe have a more single-tasking approach.

Benjamin Grillon’s studio in Paris

How did you learn how this industry works?

If I had known how the industry worked, maybe I would have become a photographer rather than an artistic director [laughing]. Both were always attractive to me when I was making music. I would take photos of the record covers I was working on because I was 18 or 20 years old and I didn’t have access to photographers. Photography interested me as a medium. I bought myself a medium-format camera. But I never thought that photography could be my profession. Even if I had, I wouldn’t have known which path to take. I didn’t come from the city, and there was no one around me who worked in an artistic or creative field. When I got to London, I immediately started work in a design agency because, in the meantime, I had done album covers, and I had a small portfolio with the covers and some flyers. That’s what allowed me to land my first job, and then, one thing led to another. I didn’t have the time to think about what I was doing and why I was doing it.

It’s never too late for a career change.

Yes, but I hate artistic directors who act like they’re photographers. Even if I love photography and I have an eye for how to compose or how to build an image, I’m not going to pretend that I’m a photographer.

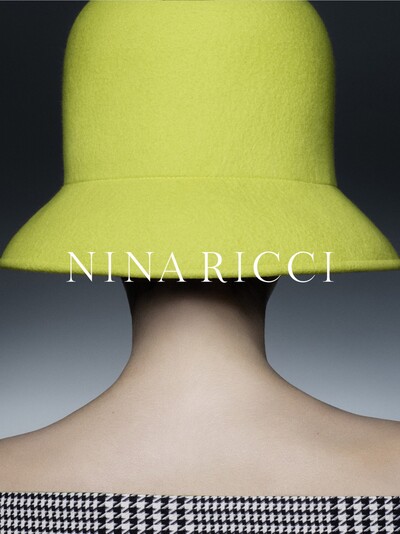

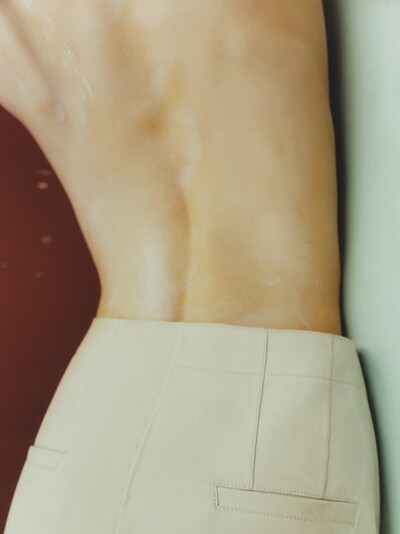

Nina Ricci Campaign

Do you not think that the career path of a photographer is more difficult than that of an artistic director? Artistic directors are more enduring in the long term while photographers have to worry about constant replacement.

Today, that is the case because Instagram has changed the way we consume images. But the previous generation—Steven Meisel, Inez & Vinoodh, David Sims, or Mert & Marcus—had careers spanning several decades. Today, it is certainly true that there has been a depreciation of the image. We are constantly consuming images on Instagram, so they have a much shorter lifespan, which leads to many more of them being produced. For that reason, there are far more photographers on the market and fashion is changing more quickly. In that sense, photographers indeed have a much shorter career.

As an artistic director, even if you can have a certain style or aesthetic, you work with different photographers and clients, so it’s easier for your style to evolve and move smoothly from one aesthetic to another, whereas what makes a photographer unique is their specific style. Even if this style can evolve, the photographer often remains its prisoner.

We find there is a strategic dimension in the approach you have with your clients and your work with them. How do you think you cultivated that? Was it during the time you spent at agencies?

I don’t know. It’s something that comes with experience and interest in the industry. I already had it even when I was making music. I didn’t limit myself to just being a musician playing bass in a band: I was in charge of managing the band, booking tours, promotion, press… and I would look for deals. When you start making music, when you’re looking for a label, you have to send demos all over the place. As a music fan, I was interested in the music industry, I was familiar with this or that label and I knew who I should send my demo to. One time I found a label in the United States; I had to find a distributor in France, so I looked for distributors. This got me interested in the inner workings of the music industry, to study management, and to end up at a record label. That’s how, at age 23, I found myself doing an internship at Universal in Paris. And that’s what made me want to go further and to go abroad. I already had that determination to understand the industry within me, so when I started working in graphic design and fashion, I just applied the same process of trying to understand where I was, how the industry worked, and who the key figures were.

Benjamin Grillon’s studio in Paris

Do you have any strategic references?

Not really… I’m going to quote M/M, not for their aesthetic approach because our styles are really different, but because they have succeeded within the big gap that exists between fashion and art… they have a foothold in music too. I think that few artistic directors have managed to remain niche doing things like album covers for Björk, visuals for theatres, national theatres, or the International Contemporary Art Fair, while also doing fashion campaigns for luxury brands. I find that interesting.

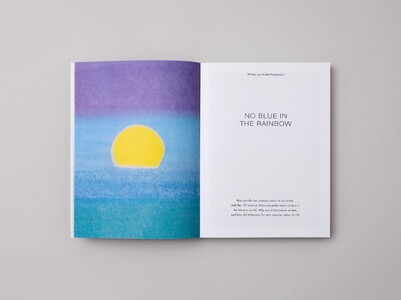

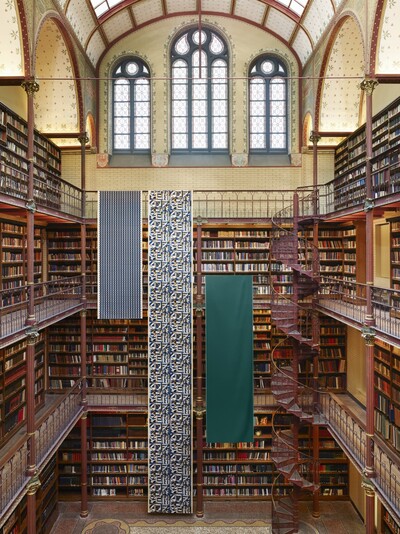

Let’s talk about The Colour Journal and Alep Editions. What role does this project play in your development? And how did you come up with the idea?

The Colour Journal was born out of a creative frustration I had when I was working for Hermès: Le Monde d’Hermès is, I think, one of the most beautiful brand magazines because Hermès has a rich history dating back more than a hundred years as well as a slightly more artistic approach that allows a lot to be told. That being said, it’s still a brand magazine, with a framework that is fairly defined and constrained by internal politics, which made it so that, even if I had a ton of fun working on this project, after two or three years, I started to become a bit frustrated. To take the next step as an artistic director, I needed to have my own platform for expression, like all those from the previous generation of artistic directors who developed their own magazines. Except that, I thought the world didn’t need yet another fashion magazine. I then started thinking about what this magazine could be and what it could be about. I wanted to talk about art, culture, travel, the world we live in, our society, but in a slightly different way. Most magazines published today are beautiful objects with a series of beautiful images, but you learn nothing from them; you leaf through them, and as soon as you close the magazine, you forget what it was about. I’m not even talking about the women’s magazines that simply regurgitate the press kits they receive. Since my job is already about creating beautiful images, I wanted to offer something else with this personal project. I had the desire to go back to the golden age of magazines such as Cahiers d’Art in the 1930s, Life Magazine in the 1950s, and certain Vanity Fair investigations in the 1970s, to combine real articles with beautiful images. Creating depth and telling stories was the starting point. I didn’t have clients on my back, so I didn’t have to make compromises. And by laying down this roadmap, I created a monster [laughs].

Helena Almeida — The Colour Journal - The Blue Issue

The Colour Journal - The Blue Issue

Why a monster?

Because three years of work, a final object that is 436 pages and that weighs 2 kilograms. That’s a fairly large cost… [laughs]

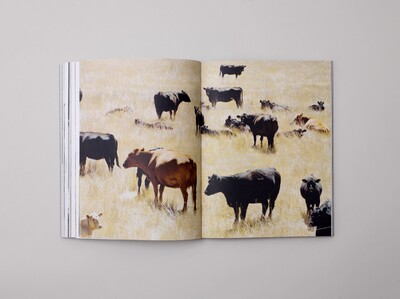

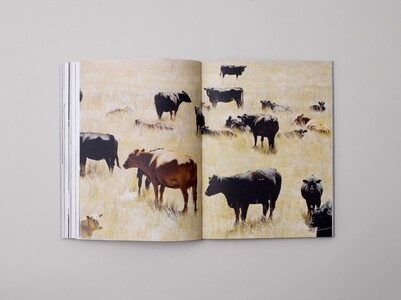

Robbie Lawrence - The Colour Journal - The Blue Issue

Sometimes it’s more complicated when you’re your own client.

Exactly.

How did you think about the financing of this project?

When the problem arose, I asked myself: will I, like all magazines, go looking for advertisers? I decided not to do a fashion magazine and not to have a fashion series so I could free myself from any constraints linked to advertisers and the fashion calendar. What I wanted was freedom. So why go looking for advertisers? Instead of investing my time in soliciting advertisers and convincing brands to follow me, I used it to do one more campaign and reinvested that money in this editorial project. Working this way let me keep the project “pure”: it is 426 pages of original content and there are no ads covering half the pages of the magazine like almost all fashion magazines today. So my professional activity finances the editorial project. I also imagine that, in the longer term, this project will serve as a showcase for me, give exposure to my work as an artistic director, and bring me clients and projects in an indirect way.

The Colour Journal - The Blue Issue

And what is the role of Alep?

In a rather natural way, while doing a lot of research for The Colour Journal, I came across subjects, photographers, and stories that did not necessarily have a place in the Colour Journal but that deserved to be given an existence. Some of the topics covered in The Colour Journal are also so rich that they would be worthy of their own book. So I thought this was the opportunity to create a publishing house for The Colour Journal and remain in charge as the publisher, and use it as a chance to develop other editorial projects in parallel.

The Colour Journal is a collection of six volumes; each volume is dedicated to a colour. The first issue, which I’m releasing in January, is dedicated to the colour blue. It brings together fifteen stories related to the colour blue. The second volume is dedicated to red. It is already underway, and I hope to release it within a year. If I did The Colour Journal full-time, I could no doubt publish one issue a year. But I have my work at the agency, and this project requires a lot in terms of research. Maybe for the subsequent colours, I could take a bit more time. I like the idea of pushing back against the sense of urgency that social media, my daily work, and fashion brands impose on me. I like the idea of taking my time with this project, of releasing it when it’s ready.

The Colour Journal - The Blue Issue

Could you go into more detail about this new relationship with time?

When I began to conceive of The Colour Journal, I also started from the observation that our generations have grown up with iconic images which belong to the collective imagination. I’m not sure, because of social media and the number of images we have to digest every day, that the new generations will have these references. I wanted to press the pause button. And instead of creating content for the sake of creating content, which is what I do every day for the brands I work for, I wanted to turn around and tell the story behind these iconic images that we all know but whose origin we aren’t necessarily aware of. I also wanted to unearth certain forgotten treasures from museum archives and bring them to light.

The idea behind The Colour Journal’s Instagram account was to start growing a fanbase. That’s exactly what we do in music: before releasing an album, we go on tour to build a fanbase so that the day we release an album, there’s already an audience waiting to buy it. I said to myself: if I start my magazine and spend two years working on it, I should already have some kind of fanbase of people who follow the project. But I didn’t want to reveal the magazine’s content on Instagram before it was released. I found it quite fun to play Instagram at its own game and do the opposite: a visual mood board based on the colour, even though the magazine is the opposite of that.

Going back to our discussion about the business model, I am trying to go beyond the magazine and turn The Colour Journal into a 360-degree editorial platform. When I was shooting in that village in China for the story about indigo or when I followed the denim hunter in the United States. I realised there was a real cinematographic dimension to a lot of the subjects. I had some incredible, unique, and singular experiences, and as I was having them, I asked myself, why don’t the photographer and I have a camera to film what is happening in front of us? This gave me the idea to develop The Colour Journal into a documentary series. So I’m trying to approach television channels or platforms like Netflix, Disney+, or Apple TV to develop a documentary series based on certain stories from The Colour Journal.

The Colour Journal - The Blue Issue

How do you think about all of your work topics? Are you surrounded by people? Do you consult people? Do you think about questions of representation and development?

Right now, Benjamin Grillon Studio is me and one full-time assistant. I always dreamed of one day having my own studio. I arrived in London 17 years ago with that idea in mind. I have been in a work frenzy ever since creating it, but after 6 years, I feel like I’m at a turning point in my development. I’ve been doing this job for 20 years, so I’m fast. I can get a lot of work done on my own and because it’s my passion, it has somewhat consumed my life. There is no real separation between private and professional life anymore. I’m getting to a point where I’m starting to lose patience with certain things, and I think that I should start changing some things. I am starting to develop my team around me so as to be more efficient. I am learning to delegate more… Of course, I can polish my thoughts by talking to certain close friends who work in the industry, but in general, all the strategic thinking—whether on the subject or on the content—remains a fairly solitary exercise.

Benjamin Grillon’s studio in Paris

Louis Vuitton - Atelier Asnières-sur-Seine

How do you manage the international dimension of your studio?

Because I lived in London for 17 years, there has always been an international dimension to what I do. That is to say, French versus English was never even a question for my magazine. The Colour Journal project is so niche that it needs to be in English so it can reach as many people as possible. Even though my mother was disappointed when I brought back one of the first copies from the printing house and she found out that there was no French translation: “Oh, it’s written in English; I won’t be able to understand it!” [laughs]. In a globalised world, digital technology has broken down borders; the creatives I collaborate with are scattered across various continents. Since my projects are also very much linked to specific places, I travel a lot all over the world. My profession is, therefore, international by definition.

And for communication, how are you managing the launch?

What I wanted to do, rather than do an official launch in London or Paris or maybe even in New York, the cities where all the magazine launches or book signings usually happen, was to do smaller events in cities that are a bit more unconventional, for example, Zurich, Antwerp, Copenhagen… to go out and meet the audience. Because it’s a bit niche, I thought if I had the opportunity to find a small gallery that agrees to invite me for an evening to put a few books on a table and a few prints on the walls, it would be an opportunity to meet people who follow The Colour Journal on Instagram and who don’t necessarily know what to expect from the print version. As for the Paris launch, I am meeting PR companies, etc. That’s what I’m setting up at the moment. I’m going to need help with the second part; I’m talking to distributors for distribution in several countries, etc. Whether it’s Antenne Books in London or Presses du réel in France…

I want to come back to the issue of representation. Have you had agents in the past?

My first agent represented exclusively artistic directors. My thought after this experience was that an AD agent—an agent who only works with artistic directors—doesn’t make sense. A photographer can potentially shoot every day or at least several times every week or month. Meanwhile, an artistic director can work on one project for several months or even a year. So the point of contact between agent and client and the frequency of discussions is completely different.

For a single artist they represent, a photographer’s agent will speak to several clients on a daily basis and gather an important mass of information: professional commercial intelligence. Conversely, an artistic director’s agent will have only one client, so only one source of information. The agent is thus cut off from a lot of opportunities by only working with artistic directors. Unless they are an artistic director agent in a traditional agency that represents other types of talent. On a daily basis, what is also complicated is that the relationship between the client and the artistic director is so strong and deep that the agent can have difficulty finding their place… and participating in the discussion every day for six months basis is not tenable.

Sketch by Benjamin Grillon

How did you learn to manage your collaborations with all the teams?

I think it has to do with each individual personality… even if it is something that can be learned and refined with experience. When you are pleasant, smiling, and well-mannered, that helps a lot in terms of human relationships. Then you need a dose of psychology to understand how to manage a client, a photographer, a team, etc. For the client management part, my experience in London helped me a lot. Anglo-Saxon culture is quite the opposite of Latin-French culture: don’t be a pessimist, never say “no,” say “yes, but”…How you craft an argument or a sentence in an email, how you reframe the problem so the client understands what you want but in a way that makes them think it was their idea. I feel like there is a very English way of doing business. This is very different from the French way of doing things, which is more direct and contentious.

What makes an artistic director unique is precisely that: you are the link between the client and the talent. We are the type of people who have both parts of the brain: creative sensibility coupled with a commercial or business read on things. You have to be able to translate what a client needs in a way that makes sense to a photographer who might not be in direct contact with the client and vice versa. We are a bit like the interpreter between the two, the go-between.

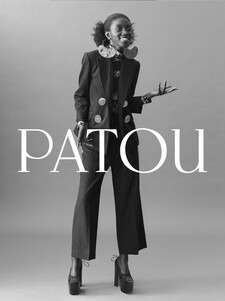

Patou - Brand Identity

Have you seen things changing with clients?

Not really; I am always surprised at how little knowledge and understanding there is of how things are done and also at the general lack of common sense. When you work with huge groups, you would think that the people you’re working with have solid experience and are seasoned in the fields of communication they operate in, but in the end, it amounts to very little. Few clients have true, 360-degree, long-term vision. I don’t know if it has to do with the fact that today, communication tools, platforms and media are evolving so quickly that people can’t keep up with the pace. Or if it is because we are outside of it, we are more nimble and flexible; because we work for several brands, we will have a more general vision, a view of the whole picture. It is becoming rarer and rarer to receive real briefs. A brief is like a problem that needs to be solved. The client asks you a question, and it’s on you to provide a solution. Instead of thinking about the true problem that the project poses, and the goal the project has to achieve, clients just end up benchmarking. Paradoxically, this means you end up copying what others do rather than distinguishing yourself from them.

Sketch by Benjamin Grillon

Hence the interest. It may even be good advice for younger people: multiply your experiences with different types of brands.

Exactly.

Broadly, how would you describe what’s happening right now with artistic direction for fashion brands? They have evolved enormously over the past 20 years and now have “mid-management,” which they did not have before.

The big difference is that it has become an industry. The golden age of the couturiers who created these houses, an almost artisanal era, is over, as is the artistic approach that came with it. Alessandro Michele has just left Gucci, which has an annual revenue of 10 billion, 40% of Kering’s total. And there is a single artistic director at the head of this brand who is responsible both for the vision, which he has to bring to life across the entire brand, as well as for the approval of all projects. The structure has remained very hierarchical and pyramidal, except that today they have become industries: is one person, one artistic director, capable of managing so much pressure on that scale? Maybe that’s also why turnover is becoming more and more important. Artistic directors stay for a maximum of two or three years, whereas before, they had a much longer lifespan. At my level, it impacts me because if I start working for a brand because an artistic director arrives and is setting up their new vision and team, and after two years, they get hired away or decides to leave, a new person comes in with a new vision and sets up a new team. I can no longer have long-term clients like the artistic directors of the previous generation were lucky enough to have, and thereby develop, a working relationship and output over ten or fifteen years with the same client.

I was listening to a podcast with Fabien Baron, and he was asked something to the effect of: “What has changed between when you started your career in the ’90s and now?” He replied: “It’s simple: back then when I was working for Calvin Klein, I was working with Calvin Klein. My contact person was the person who created the brand, who had the original vision, and who had brought the brand to where it was at the time. It was a dialogue between two people. I would present him with a campaign concept: either I could convince him, and the campaign would be carried out immediately because it had been approved, or he would not be satisfied with the result, and there would be a discussion between the two of us. Sometimes he was the one who was able to convince me. But it was simple because it was a discussion between two people.” Now, there is no more Calvin Klein because all these brands have become groups. There is no longer a single decision-making person; there is a layer of separation, I mean, various layers. Everyone is under pressure, everyone is afraid of losing their job, everyone is afraid of their hierarchy, of their superior, and everyone is targeting their superior’s position, so they try to protect themselves and make as little fuss as possible or to be noticed by the hierarchy, etc. So every creative idea is diluted by all the layers in between.

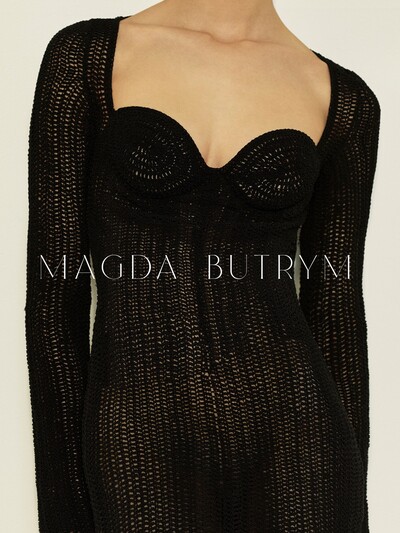

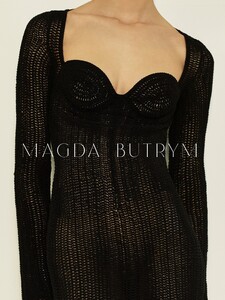

Magda butrym - Brand identity

What are the young artistic directors bringing that is new?

I kind of feel like our generation was the one that got sacrificed [laughs]. The generation before me has always been there – for 30 years. These are artistic directors who are in their fifties and who have had a fairly long career and a very traditional, “old school” approach to the profession. This is no longer possible at all today with the advent of digital technology and film; we are forced to consider a campaign from a 360-degree perspective. When we started doing Gucci’s digital magazine, we were the first to make fashion films, I think. We made between eight and twelve fashion movies per season. It was in 2010. Mert & Marcus were shooting the campaigns, but they were not making films. It was a traditional approach with four images and that’s it. The collection and the models were there, so we were shooting the next day with a film crew. After a while, they said to themselves: we want to make movies too. So they started shooting films during their photoshoot. We were doing films, but we also needed images for the magazine because before clicking to start the video, we needed an image, and the screenshots were of poor quality. So we started taking photos and found ourselves producing everything twice. Mert & Marcus, when they were shooting the campaign, shot films in addition to stills, and we shot stills in addition to films. It was getting a bit crazy.

In short… We were trying to push digital, but we weren’t taken seriously because we were still in the tradition of print campaigns in magazines. Today the paradigm has shifted completely. I don’t even know why we keep talking about print campaigns anyway or why the copyright system that benefits photographers over directors is still based on a tradition that no longer exists. Be that as it may, the new generations have no choice. They were born with it. Young artistic directors are immersed in it. But my generation is a bit like the sacrificed generation because even if a few artistic directors like me saw the potential in digital technology quite quickly and started developing it, we were not taken seriously when we started doing it. And now that we are seen as legitimate, the system has exploded, and we are competing against kids who were born with this.

That being said, there was an article a couple of weeks ago in the New York Times about a certain segment of the new generation who are starting to…

Sketch by Benjamin Grillon

Zara Home - Picasso Collection

Stop using smartphones?

Exactly. Coming back to music, when I started listening to music in the mid-90s, with the whole grunge wave, and everything, I first discovered Nirvana like everyone else, but what started to interest me quite quickly interested was the counterculture, the underground. We think that today, with the advent of social media and digital technology, we can have access to everything… that it’s a blessing for subcultures because we can communicate much more easily, whereas in my time, it was difficult to find a fanzine, a certain album or certain thing Last week, I saw the artistic director of the label where I interned when I was 23 and asked him how it was going. He told me that the music industry is not like it used to be at all. There’s no more subculture, no more independent market. Either you are a star, or you do your thing on your own, but there’s no more middle ground. We sell albums, or singles, rather, via streaming, but on TikTok. It’s kind of like we’re going back to the 45 rpm era; they release three, four, five… if there is one that works, they can have an album come out. That’s what we did in the 1960s. And that’s pretty much what they’re reproducing today with TikTok.

I hope that people continue to read and be curious and dig below the surface. That was kind of what I wanted to do with The Colour Journal. The Blue Nudes by Matisse, you can see them as posters in everyone’s bathroom and on any influencer’s Instagram grid. What interests me is telling the story behind the Blue Nudes. The one that no one knows.

Hermès - Brand Magazine

Hermès - Brand Magazine

Let’s finish with more trivial questions: if you absolutely had to do another job, in a different period of history, what would it be? Bassist? Rockstar?

What I would like to do one day is make a feature film. It’s kind of my dream. I already co-directed a short film two years ago… I have two script ideas in mind. If one day I get too old to do artistic direction, maybe I’ll devote myself to that! I could have, without a doubt, been a history teacher too. I like the idea of passing things on to the younger generations. I got kicked out of three high schools; I have always had a problem with authority, but I was lucky to have two or three super interesting and invested teachers who really helped me and opened me up to the world.

Hermès - Brand Magazine

Hermès - Brand Magazine

Are there any books that have helped you, either personally or in your profession?

I arrived in London in 2005 with the idea of having my own studio one day. It took me ten years to make this dream come true. For ten years, I looked for a business partner because all the examples I had in front of me were studios set up by pairs, and I liked the idea of having two complementary profiles, of us being able to help each other, of emulating each other, playing creative ping pong. Unfortunately, I never found the ideal person or the opportunity to do it. I set up my studio alone because my back was up against the wall. I don’t regret it. But when I arrived in London in 2005, I read two books that really helped me in my career, in my development as a designer and artistic director, and also in understanding the studio: How to be a Graphic Designer Without Losing Your Soul and Studio Culture, which are 2 books published by the same publishing house, Unit Edition, founded by two English people; Adrian Shaughnessy, and the creative director of an agency called Spin. It’s very graphic design-oriented, and I think it’s quite old because it was published around 2005. The advice is both micro and macro in nature, and it is also aimed at all levels. For example, there is a chapter on how to compose a portfolio with advice as simple as putting your contact information in your portfolio. I receive portfolios every day from photographers, young artistic directors, designers, and stylists. I think that one out of every two portfolios doesn’t include the contact information in the PDF. If I download the PDF from the email to store it in my files, I can’t contact the person again. Oftentimes, the person’s name isn’t even on there! Studio Culture is a panel of studios of different sizes from various disciplines, who are interviewed about their daily work processes, how they manage their studio, their clients, etc.

One article that fascinated me was on Practice for Everyday Life, a studio which did the identity for Tate Modern, for example, and which works a lot in the fields of culture, art, and museums. The founder of the studio said that he forbade his staff from checking their emails in the morning. The morning is dedicated to work: you have to concentrate, you get down to work, you focus on your tasks for the day, and it is only after your lunch break that you open email boxes and respond to client emails, etc.

Hermès - Brand Magazine

That’s what they are trying to do as much as possible at the GAFAM companies too. At Google, for example. What is interesting is that that’s a principle from Laborit, the neurobiologist. Right now, is there an artist or a person who inspires you professionally or otherwise?

I’m going to do another parallel with music. I have always been super inspired by a band called Fugazi for the state of mind that they created. They are the inventors, somewhat reluctantly, of what has been called “Do it yourself” and of the Straight Edge movement, which was a hardcore, anti-alcohol, anti-drug movement, etc. What I find fascinating about their approach is that they have never made concessions and that they have always been irreproachable in their way of doing business, which has aligned with their artistic approach. They are from Washington D.C. and set up a label, Dischord; they decided to promote the local scene and sign local bands. The profits they made from the sales of each album would allow them to finance the next band. They never signed a contract with any band… At one point, they hired a private investigator to track down one of the first bands they signed at the start of the label, to whom they owed royalties. The group had split up, the members of the group had disappeared, and no one had contact anymore. When they found the guys, they said, “Hey guys, here you go! We owe you this amount of money, this amount of royalties,” the guys replied: “What do you mean? We don’t want it; the idea was always to put the money back into the label to produce the next band!” When Grunge was taking off in the ’90s, and all the major studios wanted a piece of the pie, they got an offer from Sony, who wanted to buy the label for who knows how many millions, and they refused. The idea of doing everything yourself is an artisanal approach that has always resonated with me. I think that’s why when I set up my studio, I found myself doing everything myself to the point of exhaustion [laughs]. Because I have this “Do it yourself” approach and I found myself becoming a one-man band. I have always been inspired by this approach and by these guys. There are plenty of artists who inspire me every day, but maybe it’s more about their creations because I don’t necessarily know their ethos or their work process.

Gucci - Digital Magazine

Hermès - Brand Magazine

Any final piece of advice for those starting a freelance career as a graphic designer or an artistic director?

To be curious. For me, that’s the key. Beyond the fact that you can be a good entrepreneur, which may contribute to the success of an entrepreneurial or independent career, I think that the two prerogatives you need in our line of work are curiosity and passion. If you don’t have one or the other, it’s complicated. If you have passion, you’re not going to spend a single day of your life working. We are fed by something else. I’m exaggerating a bit [laughing], but that’s exactly what will allow us to overcome the complications or disruptions at work. It’s a passion for what you do and a love for a job well done.

Creation is a muscle. A top athlete trains every day. A creative person’s way of training is through their curiosity. What makes a good artistic director? General culture. Our job is to follow up on a brief, to connect elements that are not necessarily linked at first glance – to provide a reason, a story, a reference. All of this comes from general knowledge. Just because you’re an artistic director in fashion doesn’t mean you should only be interested in fashion. It’s good to know all your Vogue and Helmut Newtons by heart, but if we stick to that alone, we will have a super literal, line-for-line approach to fashion, which I think is the case with a lot of artistic directors right now who don’t have a second-level read on things: it all just becomes a visual gimmick. We enter into something quite superficial without opening up to the world. Curiosity and general knowledge: those are the keys. And I don’t know if you can work on that; I think it’s something you’re interested in or you’re not… If you’re curious, by definition, you will go out and search. Conversely, if you are lazy, it can turn into a problem and become an obstacle to curiosity.

Hermès - Brand Magazine