Hi Rozana, could you please introduce yourself?

Sure. I’m Rozana Montiel. I’m a Mexican architect. I live in Mexico City.

Rozana Montiel - Photographer: Sandra Pereznieto

How do you usually present your studio?

We are a studio that works in different scales and layers. We’re very interested in research and relations with the academic world, through teaching and obviously designing. We work in the public domain, in social projects, in private projects, in art, and in research. We call it re-conceptualizations of space and the public domain. We really come to the limits of art and architecture and we’re always trying to work with both.

Rozana Montiel Studio’s logo

What type of projects are you currently working on?

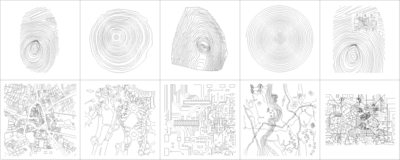

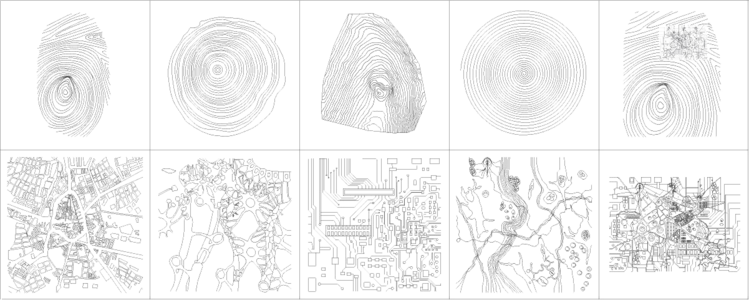

Well, we just open an exhibition in the Art Week of Miami Basel with two other architects from South America. And we are just finishing a grant project that I did for three years, which is called Zoom de línea (Zoom of lines). We research all types of lines with the idea of zooming them up, understanding their different meanings. It was very conceptual, and at the same time very architectonic and artistic.

In every project we work on, we want to go one step further. With this one, we want to make a book and an exhibition.

Casa Nidos - Claudia Rodríguez + Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura, 2021

Casa Nidos - Claudia Rodríguez + Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura, 2021

Casa Nidos - Claudia Rodríguez + Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura, 2021

Cool.

We are also finishing some social projects in Morelos, in the state of Mexico. We are starting a housing project, with the idea of resilience, sustainability, and vernacular architecture.

It’s been a busy year. What’s your current state of mind?

A very busy year. We had a lot of work during the pandemic, we worked with four different areas of the government. It was really tiring and intense for the first half of the year. We also finished a competition in Switzerland by invitation and won second place. It was actually really nice that among 15 very renowned architects, we came into second place. Part of our team was going back to Europe, going to do their master’s, so we were changing the team. There was a moment in the summer when I had to stop and think about where I could go in the next semester. It led to these private art projects, on a smaller scale. It was a very important state of mind to change scales and the intensity of work. And then again, now I’m getting ready for larger projects!

This is architecture, a roller coaster that goes up and down all the time with scale, clients, institutions, communities, changing teams and collaborators, and having fewer or more projects. I’m in a moment where I want to really think about which projects I take on and which ones I don’t and why are they important with what’s happening in the world. What we do with architecture is very important because construction is one of the most polluting and aggressive things for the environment. So how do we build today? What is important? How do we do it?

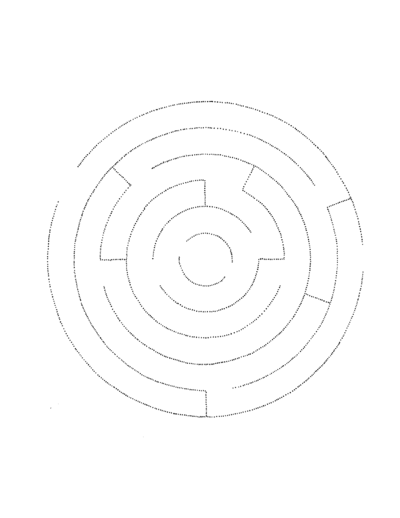

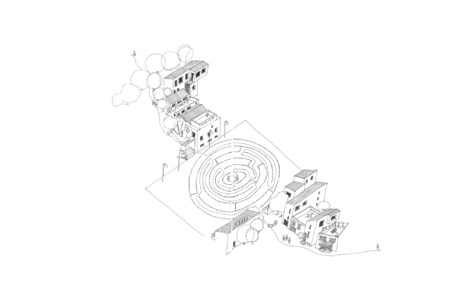

LABYRINTH, 2012

LABYRINTH, 2012

LABYRINTH, 2012

If we go a few years back, what got you into architecture? When did you start thinking you could be an architect?

My parents were art collectors. I have grown up with art all my life, going to museums. They built a gallery in our house. I slept above the gallery. They collected important Mexican art, and so I grew up with that. I always knew I liked art and space. I designed my bedroom when I was very little… My friends always wanted to be in my room because it was a very cool room, very different from others. I was not sure if I wanted to study art or design. My father was the one who said, “Well, I think that architecture gathers together all the things that you like and it’s more complete because if you study architecture, you can do art. If you study architecture, you can do interior design, you can even do graphic design. But the other way around, it’s more difficult. Because you will deal with space and three dimensions.”

So was that the time you realized that it would be your life, your work, or did you have hesitations while you were studying?

Well, the first two semesters were really difficult. Half of the people that entered left: my best friends from school started with me and then dropped out. But during my third semester, we had to do a project that was more akin to art. I had to design a Trojan Horse based on a painter. It had to walk and throw something. I understood that architecture could also be this type of fictional and ludic project. The face of the horse was glass-blown. I had this uncle that had a factory where they blew glass, so they helped me. I did a metal structure and then I blew glass. I was inspired by the Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo. It was a very creative exercise. After that, I had to design some sort of spaceship that could go into space and also water. After this semester, I decided to continue studying architecture. I really felt that Architecture was part of my life, so I went to do a master’s in Barcelona called Architecture: Critic and Project. It was a life changer going to Barcelona.

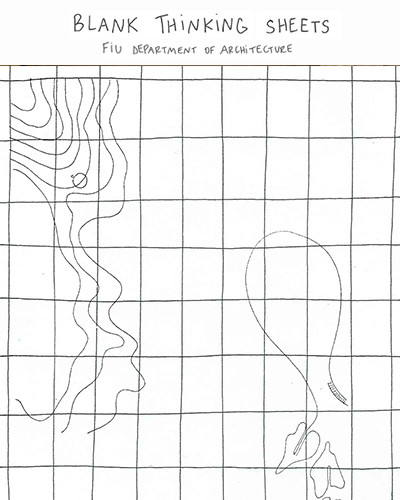

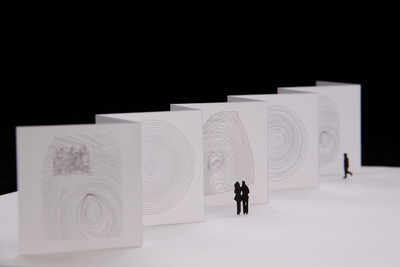

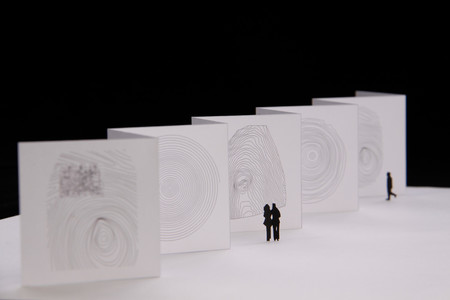

Blank Thinking Sheets exhibition

What did it change?

It changed my way of seeing architecture; I understood that architecture is much more than laying bricks, it’s also a social construction, a language construction, a narrative construction. And this is what we do at the studio now.

After your studies, when you started, did you work at any practices?

I was completely focused on studying. I loved studying. There were many days every week when I didn’t sleep, like almost every student who studies architecture. So, although almost nobody finished on time, I finished really fast because I wanted to go and study in Europe. I was working with the architect Diego Villaseñor, who’s well known for his houses on Mexican beaches. I learned from him how to get in touch with nature, to understand the context and the particularities of each site. I worked with him for two years while I was doing my thesis, which was really helpful for what I wanted to do in the future. Then I left for Barcelona.

Was the weaving between art, architecture, design, drawing, all of this… Was it part of your intuition when you launched your studio? What was your intuition when you launched? Did you have an ideal plan, an ideal project?

Well, I always felt that I had a responsibility as an architect to do social projects and to work with a larger group of people on transforming their spaces into places. I say “places”, because for me it’s where you interact with people, where you relate, where you build relationships. But I never expected that it would come out like this.

I started working with some friends in the back of an artist’s studio doing whatever projects we found, like my father’s office. This is one of the projects that got us started. I didn’t have the opportunity to start with social projects, so I had to find a different way of doing it. I always thought that I wanted to relate to art very closely, so after I came back from Barcelona I started teaching a class at the university that was on the border between architecture and art.

Also, another story with my Mexican thesis is that I entered to receive an award in Barcelona for young architects and I won it. This helped me make the decision to come back to Mexico.

Rozana Montiel studio

Rozana Montiel studio

Rozana Montie studio

You were in Barcelona, you win an award, you have opportunities to go back there, and you say, “I want to go back to Mexico”?

Yes, because I had been in Mexico for two or three months and, at the time, I had started something about design with my brother. I felt that I wanted to start my own practice, doing my own things. I couldn’t do them in Barcelona.

That’s why I decided to come back, despite having almost no work. Then I applied for a grant from the Mexican government in Mexico called Jovenes Creadores, meaning “young creators.” They select 100 young artists from different disciplines. There are architects, artists, sculptors, writers, musicians, filmmakers—all the disciplines that you can imagine. For the grant, you had to present the project you submitted, but you also had to travel three times for four days to different parts of Mexico with all of the 100 young artists from different disciplines. And that was also a life changer, something that completely changed my idea of what I was going to do because I was with some of the best artists in their discipline. Now many of them are very renowned artists. And the tutors were the most renowned from each discipline. I met a lot of interesting people there.

Rozana Montiel studio

Rozana Montiel studio

Rozana Montiel studio

So you always kept the link with art throughout your studies and your beginnings?

All the time! I don’t think it was a coincidence. I think it was something that I was looking for, but it turned out to be fantastic, unexpected in every way.

When you were studying in those years in Barcelona, what were your creative references? Who were some of the people you were looking at or were interested in? It can be in art or architecture.

Well, one of my teachers, Josep Quetglas, like all my teachers in Barcelona, was very inspiring. He has written a lot of books. He doesn’t like to travel, but he knows the work of Niemeyer and Le Corbusier perfectly. And he gave these amazing classes where we would redraw different modern houses with an active gaze, like a detective. There was also Guillem Català, for example, my other teacher, whose class was called Anatomy of the Enigma and he recited Dada Poetry in a bar… I was reading like crazy. So many books, and not only about architecture. I was also going to the movies like three times per week to see art movies by Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, Pasolini. Cinema was really important to me.

Fresnillo Playground - Rozana Montiel, Alin V. Wallach, 2017

Fresnillo Playground - Rozana Montiel, Alin V. Wallach, 2017

Nowadays, how do you make sure you maintain this level of creativity and inspiration?

When we come to the office, we have to have fun with what we do. We have to play, in a certain way. Play has been really important in my work. Sometimes I feel that I’m an actor performing in a play, and this is why I combine reality and fiction. Fiction brings a lot of things into the real world. I love coming to the office every morning, trying to invent something new. We have to bring new ideas, new references, and try to make ordinary things become extraordinary to keep on going.

Teaching is important to keep our creativity moving. I taught a seminar called Art If Act.

The seminar explored ideas on how to ACT on commonplaces with the practice of looking closely at the things we already have at hand. It is an exercise of storytelling and interpretation, a new way of activating critical thinking.

The observation of everyday life has been really important in keeping our creativity active.

I think the reason why I’m so interested in art and research is because it makes you reflect and imagine different scenarios within a different time and space of the architectonic projects.

You’ve talked about creative references, but you also have a studio, and you have people to manage. Did you or do you also have strategic references, people, or structures you are inspired by?

Well, that’s a very good question because that is a difficult part to manage. I am always thinking about the creative and amusing parts of architecture and need to focus more on this other area.

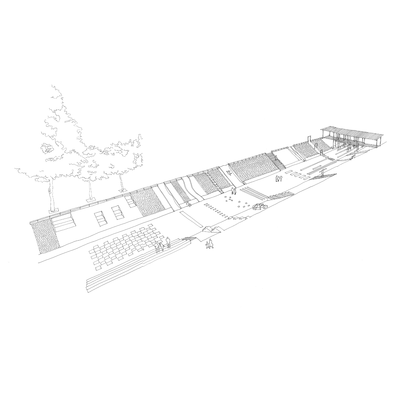

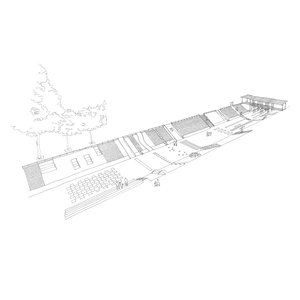

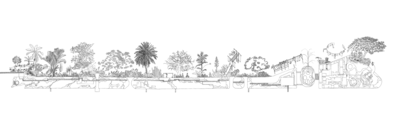

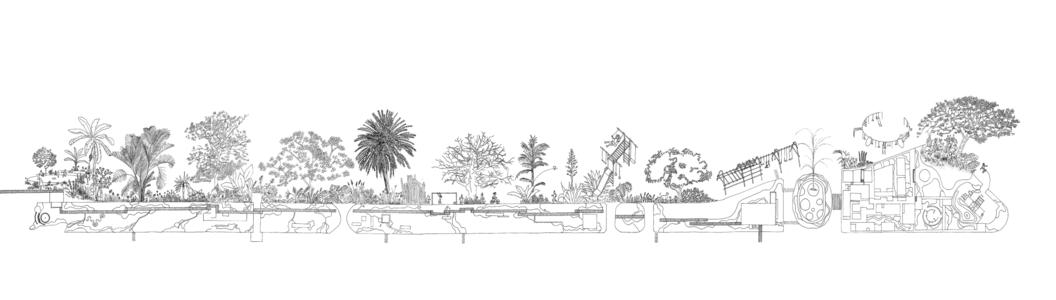

Parque Lineal Civac - Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura + Claudia Rodríguez, 2021

Parque Lineal Civac - Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura + Claudia Rodríguez, 2021

Parque Lineal Civac - Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura + Claudia Rodríguez, 2021

Parque Lineal Civac - Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura + Claudia Rodríguez, 2021

It’s also a game isn’t it?

Yes, which is really important. That’s what keeps an office going. I think one reference is my brother. He’s an ontological coach, he studies El Ser (to be). He works with human resources in different companies to help have a better development of all the people who work there. But he does it in a very creative and deep way to understand people. He brings out the best in people. I talk a lot with him, and he gives me advice on how to listen to people, how to observe and how to use language to communicate things. I think that every day you have to improve how you communicate your ideas to the collaborators, to the client, to the communities. Also, my husband

has given me very good advice. He is an architect and has had an office for a long time, so family has been very important in helping me understand how to manage an architecture office.

And in terms of development, you’ve mentioned communication, being able to communicate with your team to present your work in a nicer way. It’s essential, and you work on it. Are there any of the things you’re trying to develop currently?

We just changed the image of the office, our logo, and our website, and we are learning new ways to communicate what we do and how we do it. Transforming our gaze is a way of transforming reality, the way we represent things is a way of sharing our ideas. So I really put a lot of attention into how we show things and why, because it will speak to the work we do at the office. It’s a constant search.

Is that why you felt like it was important to write a manifesto? Was it to make sure people could understand your philosophy quickly?

Yes. Writing it is a way of seeing and understanding what I think of architecture in a more visible way. “To manifest,” etymologically, means “to be caught in the act,” so each of the 12 points of the manifesto affirms the way our design acts. We research, we think, and we act upon our observations.

Libro UH - Research

Libro UH - Research

When you’re making those decisions about your website and your communication, and also creative decisions, do you do it by yourself or do you work with your team? Is there anyone advising you?

We are a small office between 8 and 10. That’s the size that I like. When we have bigger projects, I subcontract more people so there might be 20 of us, but we’re not all in the office at the same time. And it’s just on a per-project basis. I like to keep it smaller because I am able to look into every detail; I like being involved throughout the project… Similarly, once we start a project, we get together and do a lot of brainstorming, so many of the people that work at the office are involved with every project during the initial stages. Outside the office, we work with different disciplines all the time. We worked with somebody that helped us make the web page, but we were very involved in the process and directed many of the ideas.

It seems to us that you are getting into a more international phase in terms of development. Was that a decision? Did it happen because of awards from competitions?

I’ve always loved to be in all parts of the world. When I was really young, with my parents and siblings, we used to travel a lot. Later it was by myself, and now with my husband and daughter and with friends… This is part of my life, being a citizen of the world and knowing other cultures their customs, their language, their way of seeing things…

When I studied architecture, there were few architects that you knew from other parts of the world and there was no social media… Today everything flies all over the world, they are publishing our work in China and they are calling us. Now we are all over the world because of social media. People from Europe, for example, are very interested in the social work that we do. And the architecture that is being done in Mexico. This visibility has brought the spotlight on Mexico to be recognized and seen internationally. There’s this domino effect that has brought me the opportunity to do an installation on a one-to-one scale in Versailles or participate in the Venice Biennale working between the limits of art and architecture. I also give lectures and conferences, and we are now starting to participate in international architecture competitions.

REA - stand ground photo, Photography by Sandra Pereznieto

To organize all this, it’s a big development phase. You need to give it a lot of time, I imagine. It’s bringing results, but it’s a new cycle of development. I was wondering if you are being helped by people at the studio or by external people who handle your communication since you still have other ongoing work.

Yes, but with this domino effect that I never realized was coming. And once it comes, it opens a lot of doors which I have decided to enter. We like to keep our communication internal in the office so that we are very clear on how we show the work we do.

Representation is very important to me; it is a way of conveying meaningful narratives of space but also of re-signifying our connections to space.

For example, right now we’re doing a book for an Italian editorial, Libria, who invited us to do a book about 12 of our projects. But again, we decided to change the format and do something more creative and interesting. We say in Spanish “darle otra vuelta a la tuerca.” So we will show it as a Collection of themes that we have worked on, not in a linear way, but as 16 themes with 70 lessons that we have learned as a Collezioni (like the title of the book) through the lens of different subjects that are part of our methodology of design and that are fundamental on how we understand architecture in the studio.

Los Ojos De La Architectura - Research

What would you like to do next? What are you thinking of? You mentioned you were doing more big, international competitions as well.

One of the latest ideas is to continue working with other disciplines more actively. We’re based in the centre of Mexico City and the studio is in a brick townhouse whose previous owner was Nahui Olin. Her real name was Carmen Mondragon. She was the partner of a very important Mexico painter called Dr. Atl. She was born at the beginning of the last century and her father was one of the generals that worked with Porfirio Díaz in the revolution. He built a townhouse for every one of his daughters. She was a poet, a writer, a painter, an activist, a teacher—a very progressive woman. She posed nude, wore miniskirts… She was very beautiful, very extravagant. And we now work in what used to be her house. The second floor will be used as a laboratory of ideas. The cultural part of our office will be used for workshops, conferences, as a space for reflection, as a think tank.

Well… the question was also about competitions, fully architectural competitions. Will you still have the time? Do you sometimes feel you might not want to be doing any more architectural projects? Is it something you’re debating?

I live with architecture as part of my life. I am completely passionate about it. My favourite moments are the conceptual parts of the project, the ideas, being able to play between fiction and reality. Often I think I don’t want to deal with clients, institutions, and communities but then I come back and get the strength to start again.

We have to know how to manage these emotions and must play many roles to keep an office going.

You mentioned you’re currently working with eight to ten people. In architecture school, they don’t train you on managing and handling people. So how have you managed it throughout your career?

They don’t teach you a lot of things at school. You come out and you’re trying to understand the real world, learning by doing. And so I learn every day. I’m continually learning how to do it and how to manage. How to be very well balanced while also trying to make everyone happy. We’re all working in a very nice space in a very nice house, but it’s not only about the space; the ambience and the feeling are essential.

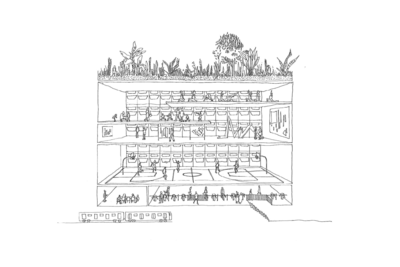

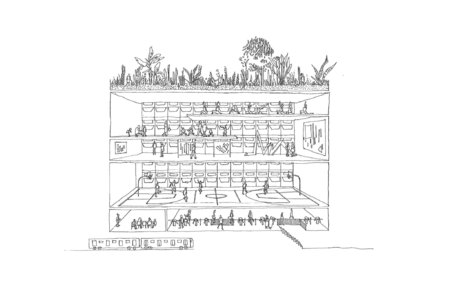

Metrópolis: utopía y ucronía - Research

How do you view architecture currently? I know that’s a really vague question, but you mentioned the relationship to sustainability, the need to think differently. How do you view this?

Well, it’s a very open question, as you said, and I think I have more questions than answers. I no longer believe in spending so much money on superfluous things in architecture. In Qatar, for example, where they’re doing these buildings, spending millions and millions. I think that things have to be more simple and have to be based on the resources we have, how to be more resilient, more sustainable, but also have to use common sense. We have lost common sense. It is very important and very simple, but we forget about simple things. It’s tough: one time, they asked me what luxury was for me. For me, luxury means that many people can have a decent way of life and have beauty as a basic right with very simple things. That’s what we were discussing with another architect, referring to the studio Abundant Scarcities. How do you turn scarcity into something abundant via the creative process alone?

Maybe we are too optimistic, but we feel that is a point of view which is shared more and more among architects, or maybe among younger architects… How do you feel about this?

Totally. 15 years ago, it was all about starchitects and spending everything you could and who could show the biggest building. And today it’s the opposite. That’s why I think Europe is looking to these other countries, to what is called the Global South. We’re not the Global South exactly, but they call us that. It’s about looking again to the lockout, to the artisans, to the basic knowledge that has been lost, but seeing it in a contemporary way and transforming it into something else.

Blank in three acts exhibition, Photography by Sandra Pereznieto

Blank in three acts exhibition, Photography by Sandra Pereznieto

Are there any other evolutions you are seeing among architects? You mentioned that Europe is looking outside Europe for once. Are there any other evolutions you’re thinking of that make you either optimistic or pessimistic?

I have always been optimistic. I think that we as architects can read under layers and give more than what we have been asked to design by listening carefully to our clients, to the institutions, and to the communities we work for. Change begins with a change in perception.

An example of change in perception is what mimes do: with their gestures and mimics they make visible the invisible, they act out a story with the movement of their body through space.

A movie about the act of seeing and looking closer, that relates to the idea of change in perception and mimes is Blow-Up by Michelangelo Antonioni. His movies were very important in my Barcelona years. The mimes keep appearing throughout the movie creating space with their gestures.

Cool. We’ll finish with some more trivial questions. If you had to do another job at another time, another period in history, what would you do and when?

I would be a writer or an artist.

And when?

Today in the present day, writing about past and future, collapsing space and time to create alternate realities. I would be taking nonlinear approaches to narrative in Virginia Woolf’s time—at the beginning of the twentieth century—or like Clarice Lispector in the mid-twentieth century with her witty humour. Or I would write poems like Nahui Olin did in Mexico or do drawings like Lina Bo Bardi the architect did.

Zoom - Research, 2008

Zoom - Research, 2008

Zoom - Research, 2008

Any other books apart from Virginia Woolf’s?

There are many good books to recommend. One of my favourite things to do when I travel is to visit bookshops and stay for hours there. I learn a lot doing this.

I am reading a book right now called Los Culpables (The Culprits) by the Mexican writer Juan Villoro. It is an amazing book. Well, all of his books are. It has become a family bond. My husband is also reading his books and my daughter is reading the books he has for kids, so we are all reading the same author and commenting on the way he writes and his stories.

Cool. And one last question: if you had to give one piece of advice to young creative talents wanting to start, what would it be?

Today, young students should learn about critical thinking.

They should look for knowledge and not just recognition. In Spanish, this is a play on words: “Buscar conocimiento y no solo reconocimiento.”

They should open new ways of getting commissions, by acting and being active, not by remaining passive.

They should really work on this. Another idea is that they have to act. Don’t wait for the project to come: go look for opportunities. Even fictional ideas can become real if you look at them with an active gaze. This is how I have been working, by looking for opportunities where the ordinary becomes extraordinary. At the office, we observe, we listen, and we ACT.