Could you please introduce yourself? For people who don’t know you.

My name is John Pawson. I’ve been practicing architecture for about 40 years now. I’m 72. Luckily, I work with 20 incredibly talented architects and graphic designers. The size of the office has been reasonably consistent.

Portrait by Rich Stapleton

How do you present your practice and your approach of architecture?

At the beginning, I met people socially or my girlfriend, Hester van Royen, introduced me to artists and gallery owners. People come to the office with a proposal and I never really ask them how they know about me. Similarly, they haven’t felt the need to ask me very many questions either. If there’s a chemistry with the client, we just start. The project is the most important thing for me and my skills aren’t really in selling. I guess all architects have to have some sort of charisma or chemistry with their clients. I remember asking Philip Johnson what was special about Mies van der Rohe – who I think is absolutely the number one architect in history. Philip was very dismissive and gave me absolutely no information about Mies. From what I’ve gathered, Mies was quite dry but he had – alongside deep inner conviction and incredible talent – the ability to convince people of a scheme, even though he was quite quiet.

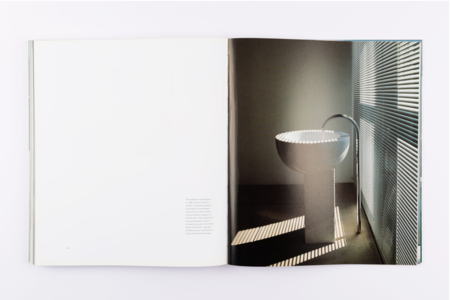

van Royen Apartment London, 1981. Photography John Pawson.

What’s your current state of mind?

I’ve personally had it very easy during the last 14 months of lockdown, because we have a house in the countryside. There have been very few cases here and I’ve been able to work from home, but it’s always been tainted with anxiety – about the disease, but also about the state of the world and how the virus is affecting other countries and people who don’t have the resources. And I find I can’t concentrate on work for more than a couple of hours. Luckily the people working with me are able to do the work from home for the moment, but you can’t run a creative studio unless everyone’s together, because you feed off one another. It’s also the case that, regardless of a client’s financial resources, people tend to take a pause when there is upheaval or uncertainty, but I can’t easily pause the studio, because it’s 20 individuals, each with their own responsibilities. So it’s a tough time, but it’s ending and we will be back to some form of normality.

Home Farm (John Pawson’s country house), Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2013 – 2019

Project Team Guy Dickinson, Stefan Dold, Matthew Bailey, Stephen Baty, Ivo Carew, Max Gleeson, Olivia Haylor, Harikleia Karamali, Nora Szuts, Douglas Tuck, Tom Whittaker

Photography John Pawson

Home Farm (John Pawson’s country house), Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2013 – 2019

Project Team Guy Dickinson, Stefan Dold, Matthew Bailey, Stephen Baty, Ivo Carew, Max Gleeson, Olivia Haylor, Harikleia Karamali, Nora Szuts, Douglas Tuck, Tom Whittaker

Photography Gilbert McCarragher

Home Farm, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2013 – 2019

Project Team Guy Dickinson, Stefan Dold, Matthew Bailey, Stephen Baty, Ivo Carew, Max Gleeson, Olivia Haylor, Harikleia Karamali, Nora Szuts, Douglas Tuck, Tom Whittaker

Photography John Pawson

You worked for a few years, before traveling to Japan, at your family business. Did you learn any business skills then, or things that you were able to use after that?

I gave it six years in the family business with my father and learned a lot about textiles, materials, form, and patterns. My father would have loved to be an architect himself, but he felt a duty to go into the company. He had a great ability to tell what any material – the weight and the blend. We got on very well with each other, but it wasn’t the career for me. When I came out, I was determined not to be a businessman. I never wanted to open an office or have my own architecture practice – it wasn’t something in my head. It just happened and in the beginning I resisted having any files, which of course is disastrous. Legally you have to keep files, but I just thought a file meant “not creative”.

It’s quite famously known that you went to Japan, thinking you could try to become a Buddhist monk, and it didn’t work out. Were you teaching English in Japan after that?

I went travelling and Japan was the first country I arrived in, in 1973. I was escaping from my father and the family business. At the same time, I was going to get married, and my girlfriend decided that it wasn’t going to work. I arrived in Tokyo just before Christmas and immediately went to Nagoya, where I had a Japanese friend, Akira, who had taught me karate when I was working for my father at the factory in Chester-le-Street, in County Durham. I met him and said I had a dream of becoming a Zen Buddhist monk. Just before I left for Japan, I’d seen this documentary about a Zen Buddhist temple with all these monks doing kendo and dressed in black on a mountaintop and had thought: “I’m 24, this is going to be the new life for me…” I don’t know what I was thinking… Anyway, luckily, Akira hung around the temple and he was able to take me back to Nagoya. That was a sort of big awakening or a big failure – clearly, it was crazy. The only other person I knew and who also happened to be in Nagoya, funnily enough, was Junko, who I had met in the Lake District in England. Her husband’s father worked in the Nagoya Business University. He said that they were looking for an English teacher, so I met the president of the university and he gave me a job teaching English as a foreign language. It was a massive about‑turn from being on top of the mountain to being in the university, which is very near Toyota where they made the cars, just outside Nagoya.

Did you enjoy teaching? Did you learn anything from it?

You always learn something from whatever you do. The teaching required a lot of preparation, which I found interesting. In my interview it had come up that I’d been to school at Eton and for some reason they seemed to think that was the equivalent of a university education. I wanted and needed the job, so I didn’t dissuade them in any way, but I also didn’t really need a degree to teach English as a foreign language. Because of the university holidays and teaching hours, I had a lot of free time, so I was able to travel and study and visit buildings.

So you started visiting more and more building sites on you free time. And then, how did you come to meet Shiro Kuramata?

When I worked in Washington, County Durham, which is next to Newcastle, I was introduced to the director of Newcastle Art School. He could see I was drawn to the work of design and said: “If you’re interested in all this, have you seen Domus magazine?” I hadn’t. I knew about Mies van der Rohe, but I didn’t know about anything really contemporary. They gave me this magazine and the first thing I saw in it was Kuramata’s work. I thought: “Oh, my God, there is somebody out there kind of visualising what I’ve been thinking”. It was absolutely what I loved and I’d never come across any other living architects before that made me feel that way.

How did you manage to meet him in Japan?

I just rang him up – I was only 23 or 24 – and I said: “I’m John Pawson from London, what about a coffee?” And he was like: “OK!”, obviously thinking: “This must be something important because he’s in Tokyo and he’s from England and he’s asking to meet…” I mean, it’s embarrassing now! He came along with Masayuki Kurokawa, also an architect, who was from Nagoya but lived in Tokyo and spoke fluent English. So the three of us had this coffee and I think they thought: “Well, there must be something more to it than this. He’s not just some random person”. So we met again and again and I went to his office and I hung around. But I only went to his office about three times and I never worked in it. I was a bit naive and young and I said things like: “You could be a huge success in Europe”. I suppose he thought I had connections and he felt, I think, that when those things didn’t happen, that I’d sort of let him down… I mean, I did finally organise a show for him in London, but I didn’t set up this company for him or promote his chair… In that sense, I think I did let him down a little bit.

If you’re Shiro Kuramata, the fashion designer you know is Issey Miyake and the graphic designers you know are all on the same level. Once Kuramata had said: “This is John Pawson”, I got to meet anybody who was anybody in Tokyo, but only for drinks and occasionally dinner. After one year in Tokyo, not speaking Japanese, things were getting a bit difficult, because they were like: “Well, who is this guy?” You can’t keep it up – as a 24 year old or 25 year old – for very long without doing anything. Kuramata said to me: “You should stop playing around and go and study architecture at the Architectural Association in London”.

So that’s when you decided to come back to Europe, to London, to study architecture?

I ran out of steam because I lived in Tokyo. I had found an amazing apartment in Yoyogi, which had a view of Mount Fuji and also of Kenzo Tange’s Olympic stadium from the 1960s. It was a tiny, tiny flat: I could touch both walls. But you could have a lot of people for dinner on the floor – you ordered the sushi and then you could have 30 people. I was in the same building as this Japanese guy who was considered the John Lennon of Japan. He was the same age as John Lennon and he was very famous in Japan. We used to go out together.

How was it to come back to England and to study after all that?

Studying was a big shock. I had never had much success with academic subjects at school – I don’t seem to be able to concentrate and pass exams, even though I’m not dyslexic. I had the shock of arriving back to European food and rooms full of furniture… And of course, the Architecture Association. I was 30, the other students were 20, it was their first time in London and most of them were trying to find a boyfriend or girlfriend, which wasn’t me. Architecture obviously was important for them, but it was lower down the list. They were having a good time. What I wanted to do was learn how to design and I was very impatient. They would arrive an hour late. The teachers seemed to understand that; I didn’t. At the same time, the school didn’t understand what I was trying to grapple with – doing things very, very simply. Zaha Hadid and Rem Koolhaas were the stars. To explain what you designed you needed to show drawings and minimalist drawings are… minimal. Just the line on the paper. It’s like Judd’s drawings, which are very beautiful, especially the simple ones, but if you don’t know where they’ve come from, it doesn’t mean anything. If you show somebody a pencil drawing of a box, an open box, it’s like: “What’s that?”

Sketch by John Pawson

How did you start your own practice – around 1981?

I was at the Architecture Association for around three years and I was living with the Dutch art dealer, Hester van Royen and I designed the flat that we lived in. She went to work with the gallerist Leslie Waddington and so I did her office there. And then I did Leslie’s office and then the gallery. After that I did a studio for Michael Craig‑Martin, who was one of their artists and then I worked for Joe Donnelly, who was one of their customers. Hester introduced me to these jobs, but it was all just following the river. It was just one incident after another. I started to pull in people to help me with the architecture, because I couldn’t do it all. As I said, the first person was an architect called Lauren Leatherbarrow from Tennessee, who had a very strong southern accent. I would think of something and she would draw it. That’s how it started. Now, I’ve got 20 brilliant designers, draftsmen, and architects.

You had those types of jobs for around 10 years until you met Calvin Klein?

Calvin was looking to open his first shop, a flagship store. He’d met with Luis Barragán and discussed doing a shop with him. He’d also had his apartment done by Joe D’Urso. I think he would have liked to be an architect himself and he was looking for a young architect that he could work with. Ian Schrager gave him the first book about my work, published by Gustavo Gili and turned up at my office with that book in his hand in 1993. In the morning – before I knew any of this – I’d had this meeting with an English property guy who was trying to explain to me about loft living. I’d been in New York in the 1960s and I knew about lofts, so I was polite, but I was also angry and frustrated, so I had gone out for lunch on my own, for spaghetti and some chianti. When I came back to the office and they said to me: “Oh, um, we’ve had Calvin Klein on the phone”, I thought it was a joke. In those days, Calvin Klein was like a mythical figure. When I finally called him back and said I’d be delighted to meet him, he said: “Good, because I’m outside”.

John Pawson and Calvin Klein, Calvin Klein Store, NYC, September 1995. Photography Todd Eberle

Did your time in Japan with other famous designers, architects, help you being cool with meeting Calvin Klein and then working with him?

The thing about Calvin is that he’s incredibly charming. What I think has set all those kinds of people apart is that they’ve personally made the contact. There is no going through managing directors or CEOs. In person, Calvin’s very disarming, so he made it very easy. The same way Ian Schrager is very attractive and great fun.

Schrager Apartment, New York, 2006 – 2009

Project Team Stefan Dold

Photography Gilbert McCarragher

Schrager Apartment, New York, 2006 – 2009

Project Team Stefan Dold

Photography Gilbert McCarragher

Before the store opened, did you have this intuition that it would be a turning point?

The difficulty for me was that I had an idea to do something small, for myself. I wanted to get things built that I had in my head, so I wasn’t really the best architect for my clients, because I didn’t really listen to them. Clients talked about compromise. To me that was an awful word, but they kept telling me that compromise was a wonderful thing – that this is how the world works. So I managed to alienate three of my biggest clients.

By the time Calvin came, I had been used to making all the decisions myself. Calvin had his own aesthetic, he had his own design ideas and I was there to make his store. That was a big learning curve that really changed my thinking, because I started to listen. I realised how important the client and the collaboration are. There were so many things that I disagreed with him on the store. He brought in Joe D’Urso to help with the interior and the furniture and that upset me. I had to hang in there, otherwise I would have lost the job. I lost the battles and won the war, I guess. (laugh) My work is about the details and a lot of the details are Calvin’s. He liked contrast, I like less contrast. But you know, we got there.

And he brought you other types of clients.

Absolutely! I’ve been working for 40 years! Where has the time gone? But all the way through, my career has been built on a collaboration with other people. I’ve been very lucky, but it’s this harnessing of other people’s talents and creativity.

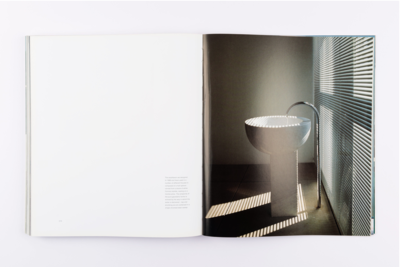

You were talking about an abbey. Did the abbey of Nový Dvůr, really come after having seen the Calvin Klein store?

I heard this and at first I imagined that the abbot and prior must have gone to the store, but the reality is that the abbot of Sept‑Fons, the mother‑house in Burgundy, had been given a copy of Minimum, the book I’d written to try to explain my approach to architecture. They’d opened it and seen a picture of the Calvin Klein store and there was a long table at the centre of the photograph, which they thought would make an altar.

Calvin Klein Collections Store,

Project Team Enzostefano Manola, Vishwa Kaushal

Photography Todd Eberle

Abbey of our Lady of Novy Dvur Bohemia Czech Republic, 1999-2004

Project Team Pierre Saalburg, Vishwa Kaushal, Stefan Dold, Stéphane Orsolini, Ségolène Getti

Photography Hisao Suzuki, Connoly Weber Photography

Abbey of our Lady of Novy Dvur Bohemia Czech Republic, 1999-2004

Project Team Pierre Saalburg, Vishwa Kaushal, Stefan Dold, Stéphane Orsolini, Ségolène Getti

Photography Todd Eberle

Abbey of our Lady of Novy Dvur Bohemia Czech Republic, 1999-2004

Project Team Pierre Saalburg, Vishwa Kaushal, Stefan Dold, Stéphane Orsolini, Ségolène Getti

Photography Hisao Suzuki, Connoly Weber Photography

How did you maintain your level of creativity, through collaborations?

I’ve always needed to work with somebody. I can’t sit on my own and sketch and come up with all these ideas. I’m also very impatient and not skilled at drafting. I just need to convey something to the guys in the office, observe its development and have the final say. The body of the work is the sum of a group of around 20 people, a lot of whom have been with me for more than 20 years. They’re not necessarily minimalists. They all have their own strong aesthetic, but for the time they’re with me, they try and fit in with the rules. I’d always rather have a good architect than a minimal architect.

Do you monitor what’s going on in architecture or do you prefer to focus on what you really feel like?

I have never tended – and sometimes this is a mistake – to keep an eye on what other people are doing or what’s happening out there. We have all these books, but they’re not for me. The office seems to like books, but we don’t have things open and say: “Well, the monastery should look like this”. The ideas are worked out and we keep on working at them until we feel we’ve got something special.

How do you meet and select the people you’re working with in Kings Cross or the ones you’re working with internationally?

Most of the jobs we do require executive architects, who produce the construction drawings from our design drawings and supervise the project site on a day to day basis. The relationship is particularly important, because the majority of our work is outside the UK. Usually I’m happy if the client recommends a local architect. Over the years we’ve had relationships with local architects who have made the job so smooth and easy and then we’ve had other ones who made it a nightmare. But you have to deal with that. There is no point in complaining. Occasionally, of course, we interview the prospective candidates. I can see that it must be a difficult role sometimes, facilitating someone else’s vision.

Paros House I, Paros, Greece, 2008 – 2016

Project Team Douglas Tuck, Fabien Pinault

Photography Douglas Tuck

Paros House III, Paros, Greece, 2008 – 2016

Project Team Douglas Tuck, Fabien Pinault

Photography Douglas Tuck, John Pawson

You’re also designing products. Does it come from an architectural vision, and then you think: “Oh, we should do that”?

Oh, absolutely. We are architects, but for me the interior is as important as the exterior. It is so easy to fuck up the space and that’s what I’m trying to protect. The positioning of furniture, the choice of furniture, the furnishings: they are really, really important. Which isn’t to say that you can’t have other people’s things – that you can’t mix your own work with other classic or contemporary designs. I particularly enjoyed designing knives and forks, glasses and plates, which started as a idea to equip the refectory of the Cistercian monastery I designed in the Czech Republic with a set of simple, visually quiet pieces for everyday use.

Interior of Abbey of our Lady of Novy Dvur Bohemia Czech Republic 1999-2004

Project Team Pierre Saalburg, Vishwa Kaushal, Stefan Dold, Stéphane Orsolini, Ségolène Getti

Photography Hisao Suzuki, Connoly Weber Photography

Abbey of our Lady of Novy Dvur Bohemia Czech Republic, 1999-2004

Project Team Pierre Saalburg, Vishwa Kaushal, Stefan Dold, Stéphane Orsolini, Ségolène Getti

Photography Hisao Suzuki, Connoly Weber Photography

If we go back to the way you developed your practice, you’ve mentioned a few creative references. Did you also have some business ones, apart from seeing your family run a business?

I’ve always resisted and fought being business‑like. Luckily Catherine, my wife, has a very good sense of money in and money out. When I first met her, I was taking taxis and eating in restaurants and I had no money. She was like: “The first thing you stop is eating out and taking taxis. You get the bus and you have a sandwich”. I was like: “Oh, wow”. That’s all you need to know: money in, money out. And the money in has to be more than the money out, I guess.

After the Calvin Klein store opened did you get new prospects coming in, or calling in? Did you have someone inside the practice being able as well to monitor what could be interesting in terms of business development?

I’ve never worked for another architect, so I don’t know about other architectural practices, but we’ve never gone out and looked for work, it has always come to us. Which isn’t to say there is a ceaseless torrent of potential projects. The offers come in and we look at every single one. We always try to say yes, but at the same time, there is a natural filtering process. If a client has a project that is unrealisable, or the chemistry doesn’t work, they understand and may decide not to go ahead. Obviously, something like Calvin or Cathay Pacific – which came because of Calvin – they were thinking about using us, but they needed some reassurance because we were a relatively new practice.

Is there anything you consider essential in terms of developing your practice?

Well, it seems disingenuous, but I keep saying that I’ve just followed the stream. I’ve just followed the river in my life and not ever had this vision from the beginning of my life to the end of it. It’s the same with the architecture. I’ve built a body of work, project by project. People have preconceptions of what I do, of what I am ‑ they always want to put you in a pigeon hole. They used to say: “Oh, you’re the guy that does flats or interiors”. And then we became the people that did Calvin Klein. And then suddenly, I became the guy that did the books.

Minimum, Phaison Press, 1996

Author John Pawson

Design Stephen Wolstenholme

Book photography Gilbert McCarragher

The books are a very good example because it’s also a very creative thing and a good thing to share. It’s also a development tool. When you released Minimum, were there any other intention than sharing, or was it to document your work as well?

The documenting of the monographs or the books on the work is a way to move forward. It’s important for me and for the studio to analyse what we’ve done and how we can do better – to have an overview every five years or so, to see where we want to go next. It’s certainly not in any way to proselytise.

Regarding Minimum, Phaidon said they wanted to do this book and I said yes, went away and came back with a proposal. I thought they wanted me to write 100,000 words, which was what I was poised to do. And they said: “We’re an illustrated book publisher, we don’t do words, we do photographs”. So I wrote 10,000 words and chose a lot of photographs. I didn’t expect it to be as successful as it was. Mini Minimum, the small version – which was Phaidon’s idea – sold 110,000. For an architecture book to sell a few 1,000 is considered a bestseller, so 100,000…

Minimum, Phaison Press, 1996

Author John Pawson

Design Stephen Wolstenholme

Book photography Gilbert McCarragher

What’s the idea behind your last book Home farm cooking – still with Phaidon?

I did my first cookbook 20 years ago, with Annie Bell. The book was called Living and Eating. It came about because Annie was the wife of Johnnie Bell, who was the landscape architect in my office. I knew she was a professional cook, so I asked her to do the menu and the cooking for a Martha Stewart photographic shoot in our house. Afterwards, she said: “We should do a book together” and the book we wrote went on to become as a sort of cult title in America. Phaidon has been keen to commission a follow‑up John Pawson cookbook and this time it made sense for the collaboration to be between me and my wife, Catherine, because it’s all about how we cook at our home in the Oxfordshire countryside.

Home Farm Cooking, Phaidon, 2021

Authors Catherine & John Pawson, Foreword, The Architecture of Home by Alison Morris, Commissioning Editor Emilia Terragni, Project Editor Sophie Hodgkin, Production Controller Jane Harman, Photography Gilbert McCarragher, John Pawson, Natasha Stanglmayr, Design Nicholas Barba

So you do cookbooks but you don’t cook yourself?

Yeah. But then I also don’t build the houses myself…

I wonder what’s your relation to words. Do you describe your projects precisely, in details?

The words have always been very important. It’s maybe down to having had Bruce Chatwin as a friend and client, who obviously was the best English writer I’ve ever met. I asked him to write a short piece for me in the 1980s and I watched him spend a week writing 800 words. I’ve always thought that words are a better way to describe architecture than photographs. They’re more evocative. Even when you see the real thing, to sort of almost have your emotions explained, it’s quite useful. For me the test of architecture is that, when you walk in, you will be moved. You can see people physically change when they enter a space. And Bruce could convey that.

When the boys were small we went on holiday and one of the people staying there was a girl who taught very young children. I don’t know what I sensed, but I knew she could write and I managed to persuade her to write one day a week for me… She’d never written about architecture before. And for the last 20 or 25 years, I’ve been trying to get her to write for me five days a week.

The Design Museum 2010-2016

Project Team Chris Masson, Jan Hobel, Mike Shaw, Francisco Tojal, Allan Bell, Stefan Dold, Fabien Pinault, Tiago Frazão, Reginald Verspreeùwen, Eleni Koryzi

Photography Friederike von Rauch

The Design Museum 2010-2016

Project Team Chris Masson, Jan Hobel, Mike Shaw, Francisco Tojal, Allan Bell, Stefan Dold, Fabien Pinault, Tiago Frazão, Reginald Verspreeùwen, Eleni Koryzi

Photography Friederike von Rauch

There’s no account for the practice and its projects on your instagram account, which is very personal. You have to go on the website to really look at all your projects. Is it because Instagram’s saturated? Was it conscious?

No, it wasn’t conscious. Catherine said to me, five or six years ago: “You should be doing Instagram”. My response was that I didn’t know how and didn’t particularly want to anyway. So she got my son to set up the account and Catherine posted the first pictures herself, which I think are still there. Suddenly, I realised what it could be for me – my photographs and my personal view. We had a trip to South America – to Chile and Argentina – and then New York and I started to just post things as I went along. And obviously the house in London and the house here in the Cotswolds were easy, because I spend so much time in them. Our own work was more difficult to document. I can’t take photographs and talk and there’s a limit to how interesting or beautiful a photograph of a building site is. It’s also the case that the photographs I take of building sites or projects are like a snagging or to do lists. But more than anything, my Instagram isn’t about creating a platform for the work, it’s about documenting a point of view.

You mentioned you were surrounded by really strong creative talents – you mentioned copy writers, architects obviously, graphic designers as well – what are the different roles there in the studio? Are they all creative people or do you also have project management people?

Catherine is the business brain and the money person, but she’s at home. There are between 20 and 25 people in the studio. We’ve got two graphic designers, Nick and Max, and the rest are architects, ranging in age from 20+ to 50+, half women, half men. There’s no receptionist, no secretary, no human resources, and no cook, just a very nice Polish cleaner who comes in at night.

Moritzkirche, Augsburg, Germany, 2008 – 2013

Project Team Jan Hobel

Photography Gilbert McCarragher

Moritzkirche, Augsburg, Germany, 2008 – 2013

Project Team Jan Hobel

Photography Gilbert McCarragher

You mentioned you didn’t want to become a businessman, so you probably didn’t want to become a manager either.

As I said, we’ve got around 20 people at any time. Most of them have been there for longer than 10 years, and five or six have been there for more than 20, so whatever I’m doing seems to suit them. I mean, I get very frustrated, I lose my temper, but I haven’t done that recently, because I haven’t been at the office. So I’m not perfect. They don’t like it, but they put up with it, because there’s a lot of independence and all the jobs are interesting. Obviously this year is a bit difficult, but I’ve made a point of making sure that the salaries are significantly higher than in other offices in London. It’s what I would call a shutout call. I don’t ever want someone coming and saying: “Can I have a word with you? I think I should get a bit more”.

What’s your view on architecture at the moment?

Well, I’m not a good person to ask, because although I’ve been doing it for 40 years, I’ve tended to keep my head down. If you work really hard and concentrate on what you’re doing, then at the end of it you will have a body of work that is satisfying. I’ve never been interested in legacy. I’ve never thought about what happens after this.

Lacaton & Vassal won the Pritzker Prize, which was very surprising. At the moment, architecture – just like other industries – feels like it’s dealing more and more with what’s already existing, considering what’s sustainable, what can be recycled, what we will do out of the buildings we build. We feel that also in a way it is quite present in your work.

That’s always what I’ve done. Half the work we do is trying to restore, in a sensible way, existing buildings. Sometimes you want to say: “Oh, do you really need to build this?” (laugh) I thought the Pritzker was a great choice. And prizes are a funny thing, aren’t they? It’s very pleasant to win things, but I think if you have that in mind, you become very disappointed when it doesn’t happen.

Sketch by John Pawson

At the moment, there’s more and more interest in the sustainability of the building. When you recently built this hotel in Tel Aviv, was your consideration not to destroy anything?

Of course, some things are worth keeping. When you work on a big project like the one in Tel Aviv, you don’t have 100% control. Aby Rosen was the owner, he bought it in 2005 and the work finished in, like 2017, or 2018. So for me, it was an incredibly long project. When we were digging down the foundations, we were uncovering different archaeological layers, of religious, historical, and architectural significance, which was fascinating, but brought its challenges and slowed the process.

Are there any potential evolution or developments you think for your practice, and projects you’d like to do?

People always say: “Why don’t you do social housing?” or “Why don’t you do hospital, skyscraper, or airport, or urban planning?” Of course, I would love to. When new project types have come up, I’ve always embraced them, whether it’s designing a bridge, or a yacht or ballet sets. I’ve been very, very privileged in the people I’ve worked with, so I’ve never really thought in terms of a wish list.

Abbey of our Lady of Novy Dvur Bohemia Czech Republic, 1999-2004

Project Team Pierre Saalburg, Vishwa Kaushal, Stefan Dold, Stéphane Orsolini, Ségolène Getti

Photography Todd Eberle

I have a few more trivial questions, we like to ask everyone: if you had to do another job at another time, any other historical era, what kind of job would it be, and when?

As you know, I’ve done so many jobs before I found architecture. I was relieved that I had a facility for this.

Are there books which have really helped you in your development, or in your practice?

I’ve been reading the book about Mies’ relationship with Edith Farnsworth and the building of the Farnsworth House. It was interesting for me, because of having gone and stayed in the Farnsworth House. It was one of the most sublime architectural moments in my life: the proportions, the details… And then to read this story of a woman who provided the money and the land, but it wasn’t what she wanted. I mean, she wanted the man! They met romantically to begin with, so she gave him the commission. She was always going to build something, but she gave it to this guy that she was having an affair with. And of course the affair didn’t last and the relationship didn’t last. And he built her the most extraordinary piece of architecture in history – or one of them – and she hated it. She even left America to get away from it and sold it to Peter Palumbo. I mean…

L’Anatomie de la Sensation Opéra Bastille Paris, 2011

Project Team Mark Treharne

Photography Richard Davies

You very often refer to your “untidy mind”.

I constantly start something and then move to something else. That’s why I was very lucky to be in partnership with Claudio Silvestrin, because we were so different. He was fantastic, because he’d have a drawing in front of him and he’d say: “OK, what are we doing about this?” And he wouldn’t let me turn the page until we’d finished it. So we got through these things. That’s why we split up eventually, because I was getting in the way of his career and upsetting the clients and it was a mess. It was completely my fault. But I guess I’m better on my own really. I find it’s very difficult having a partner, except for Catherine.

When was this partnership exactly?

Years ago, but it still comes up. From 1986 to 1988 or 1989, I think, or something like that.

Do you have any advice for a young creative talent who would like to start an architectural practice, a minimalistic one?

The most important thing is that people should do what they want to do, regardless of money or what their parents or friends say. At school, they said to me: “Pawson, you can’t do architecture, because you can’t do maths”. And then my father said to me: “You can’t do architecture, because you pay architects to do the work, you don’t do it yourself”. And so on. Any parents that come to me and say: “My son or my daughter wants to do architecture”, I say: “Fantastic!” You’ve just got to do what you want to do. The satisfaction will follow – not necessarily the money, but the satisfaction. You just need a client and it’s quite good to have somebody to work with, because it’s quite lonely otherwise – I spent a lot of time in the office on my own in the beginning.

Without clients?

Yes and the worst thing is that you’re on your own and the telephone doesn’t ring. I would go out and when I came back there’d be no flashing red light, meaning no messages. I had this pristine white office, an immaculate desk and everything was very cool, but no work and no people. And now I’ve got the most untidy office in history with 20 people. And I mean, it can be quiet, but there’s lots of stuff and people are always surprised because they’re expecting a row of 10 Buddhist monks…