Could you introduce yourself in a few words?

My name is Clémentine Berry. I’m thirty-four years old and I live in Paris.

Clémentine Berry

And in a few more words?

I grew up in the country, and came to Paris at eighteen to study at the Olivier de Serres school of arts and crafts. Then I went on to the Arts Décoratifs de Paris, and after graduating I opened a studio called Twice with my friend Fanny Le Bras.

Twice Studio’s door

Could you tell us a little about your studio?

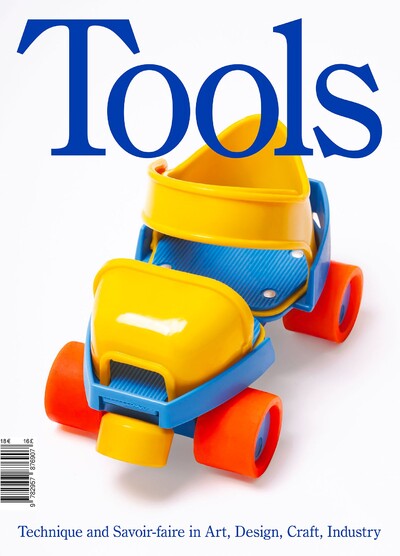

Twice is an art direction and design studio, we’re working with the public and private sectors, for cultural and other subjects. We’re specialized in visual identity and art direction. We also do some scenography, some web design, a lot of publishing and a lot of art direction and photo shoots for the magazine we just launched, Tools.

Fanny left the studio nearly a year ago to devote herself to her other passion: cooking. She’s going to be a chef. I took over the studio and kept the team together: our graphic designer Malou Messien, and other collaborators depending on the project, the demand, the particulars. If we need to do animation, we have somebody for that, same for typography.

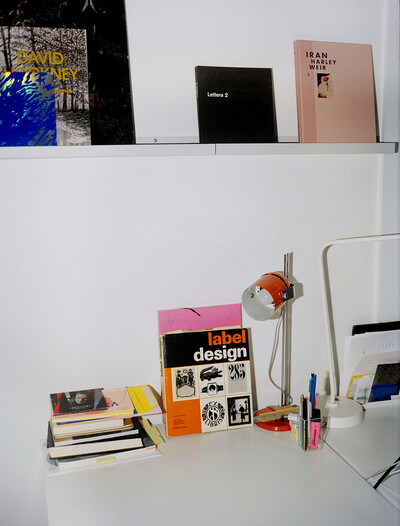

Twice Studio’s office

Twice Studio’s photocopy machine

Hearing you talk about it makes it sound very simple, though it can be pretty tricky. Could you tell us a little more about the separation? How did you manage the transition from two to one?

Also, is it a coincidence that Tools came out following your separation?

At first I was super freaked out to be alone because, I mean, we’d been working together for ten years. I would see Fanny every day; we went through hard times and experienced really cool things too. And then boom, all of a sudden I had to face everything on my own. It was also hugely motivating, like a swift kick in the ass. I told myself: go for it, now is the time to launch the projects you had in mind. And so I launched Tools. And I’m pretty proud of it!

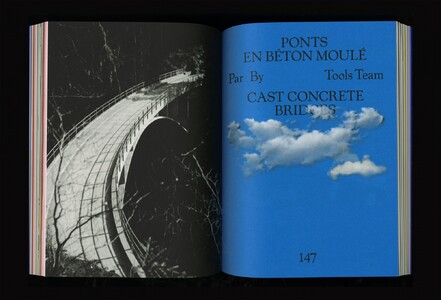

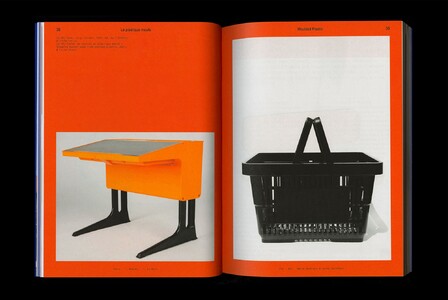

Tools Magazine cover

Could you present Tools, please?

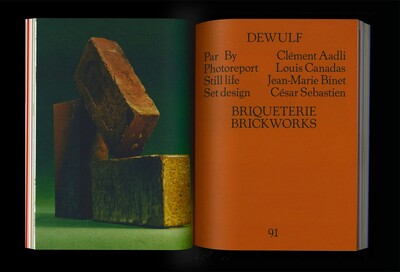

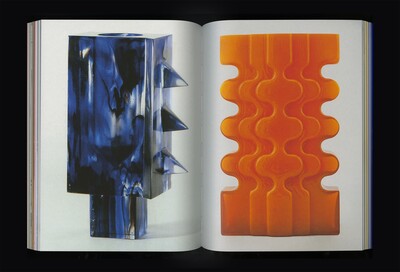

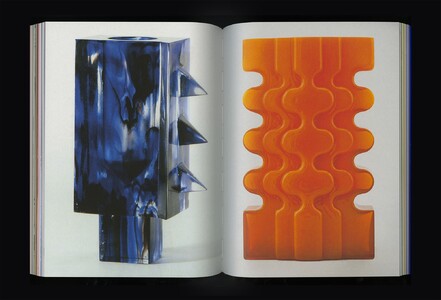

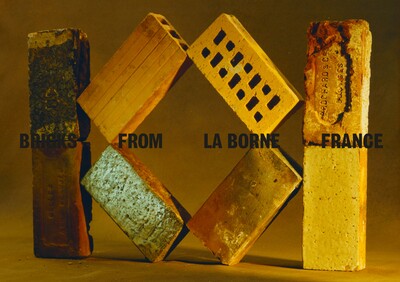

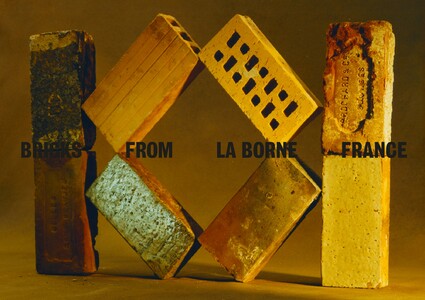

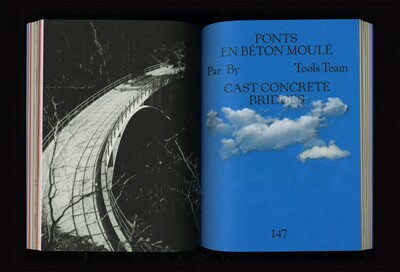

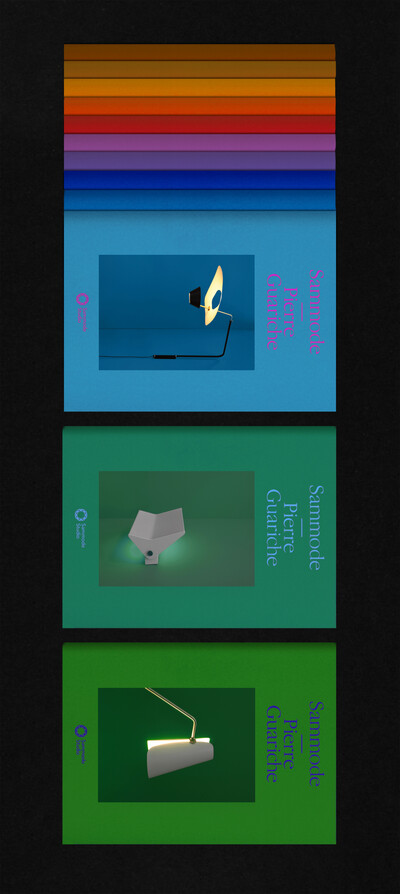

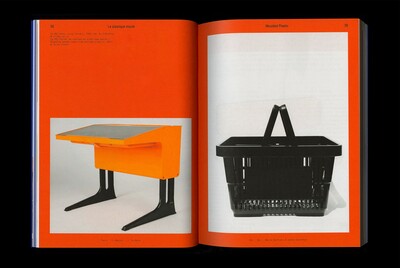

Tools is a magazine devoted to techniques and know-how in design and other creative fields. The idea is to share know-how. Each issue is devoted to a theme. After one year of work we brought out an issue in September on molding and we are currently working on issue number 2, which will be devoted to weaving. In each issue there are reports from the factory floor or from people’s homes, people with a fine-tuned knowledge of the theme at hand. Interviews, portfolios… for example, open the magazine at random and you might come upon a portfolio on molded glass vases, features from the editors, an article about old-time cooks sharing their kitchen secrets and the best cake mold to use; we went to visit a brickyard… there are lots of different articles on various molding skills.

Tools Magazine, Photography by Jean-Marie Binet

Tools Magazine

How did you get the idea?

I have always been rather passionate about technique and understanding how things are made. I find objects fascinating, and love learning and telling their story, because these stories are about people, about society. My parents were farmers, so I know all the techniques for growing vegetables. I want to shine a light on craftsmanship and personalities. Sometimes people learn from their parents, sometimes they’ve been to school, but what they have in common is that they are all passionate about what they do, and it’s interesting to share that, to go and meet them and discover all of that, and I hope it’ll be interesting to read in the magazine.

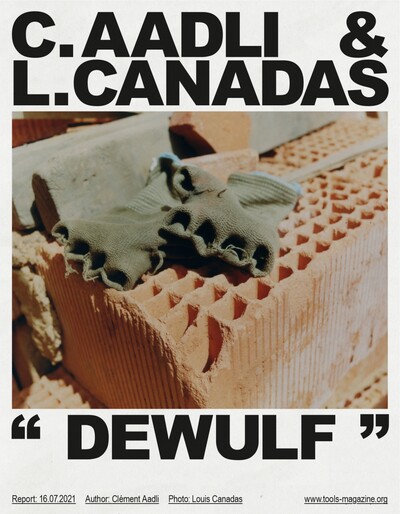

Tools Magazine, Dewulf shot by Louis Canadas

Tools is all about technique and craftsmanship, yet you yourself are more image-oriented. How did you make that leap?

Learning is my great passion in life. And here we’re talking about people who do incredibly sophisticated things that you’ve never seen anywhere else. And then of course I have always loved objects, ever since I was a little girl. I remember in high school we worked on graphics but also on design. At fifteen I was already into understanding things properly, seeing the designs of objects, to see things in volume. Except that I always sucked at spatial design. On the other hand, making images is something I’m comfortable with. It’s easier. This project is a blend of all my basic passions.

Tools Magazine

Could you tell us about Tools’ economic model? To be fully transparent with our beloved readers, we were involved in the project, but we were hoping you might want to comment on it?

Well, I can tell you that the first issue was made with no money, not a cent, I paid for almost everything, even though I lucked out by getting a little Hermès ad at the last minute! So there wasn’t much of an economic model per se. It was rather, I’m going to do this and let the chips fall where they may. I had some mates help me for the texts, some photographers also volunteered their services because they dug the project, etc. Now for issue number 2 we’re getting more professional, we’re asking for grants and subsidies and we put together a nice press kit for some cool brands that contacted us, the idea being to leave some space for ads. We’re not looking to turn a profit, just make enough to pay the people we work with.

How do you hope to keep Tools going and how will it coexist with Twice?

Each enriches the other. Through Tools I sometimes meet people who might be in need of an art director, something I can do with Twice. Also, the people involved in Tools get to work with Twice. It would be good for Twice to work with design brands for example, without limiting us in any way.

There are lots of other things that can be done, because we’ve been meeting loads of craftsmen and designers who have great projects going. Moving forward, we’re going to need to develop it, perhaps producing objects… For example, François Bauchet designed a tea set a few years back for Vallauris. I love it. I think we could do something with him, a limited edition for example, with a craftsman who would build the mold.

Producing objects is a rather heavy undertaking, so we could perhaps begin with a very limited number of pieces and see how it goes, because it’s an amazing experience as well as a great way of communicating. I tend to cast a rather large net, so I see countless objects and prototypes coming out where I think to myself that someone should produce them. Say, a craftsman/designer collaboration, or else brands collaborating with craftsmen.

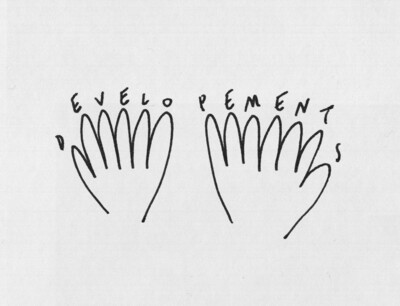

Sketch by Clémentine Berry with a spelling mistake

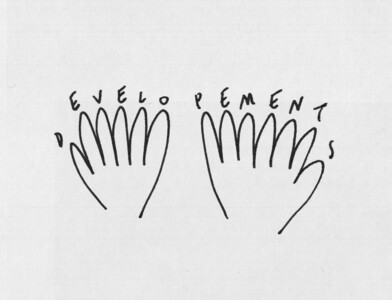

Sketch by Clémentine Berry with the spelling mistake corrected.

How do you develop your ideas?

When I’m working for a specific client I get to do one of the most enriching things in our line of work, which is embark on a deep archival dig to the very heart of the project. With a client who’s got years of experience, we like to go through their archives to get a sense of what has been done from their inception until now, why they want a new identity, why they want to communicate differently, why they want a campaign… You need to know the entire history of their projects. By exploring the archives, by diving deep — that’s where you find the nuggets; then you get creative and come up with a true expression of who they are.

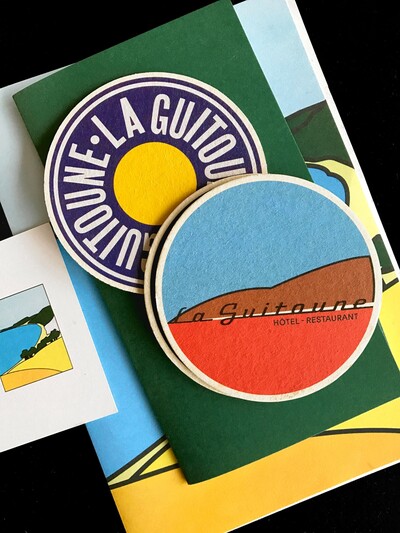

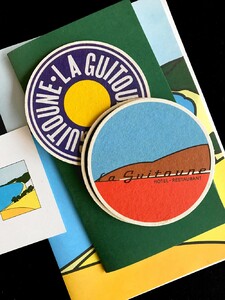

La Guitoune Identity

What do you feel have been your most successful projects?

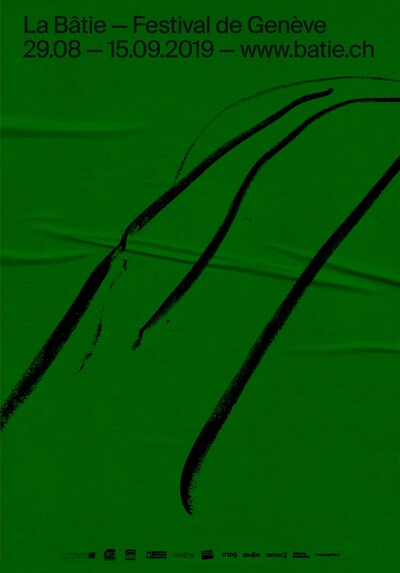

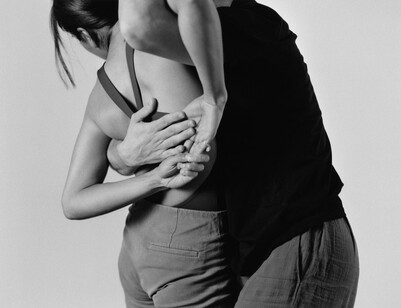

Unsurprisingly, La Bâtie, the Geneva dance, theatre and music festival that began in the 1970s and with whom we collaborated over a three-year period. When we got involved, we explored the archives in order to grasp what had been going on visually throughout all those years. Some great things had been done but never had there ever been anything remotely connected to the body, which we found somewhat odd for a dance/theatre/music festival. We thought we absolutely needed to show bodies in the pictures, at least during the first year of the campaign, the very heart of the identity. We had zooms and macro videos and shots of bodies moving and we conveyed this through all the various media: posters, trailers…

La Bâtie-Festival 2018

La Bâtie-Festival 2018

La Bâtie-Festival 2018

How did it go after that ?

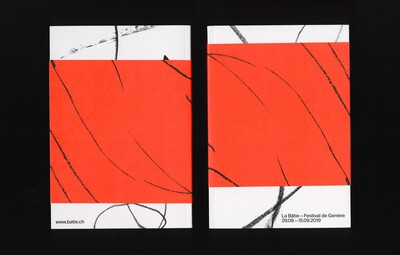

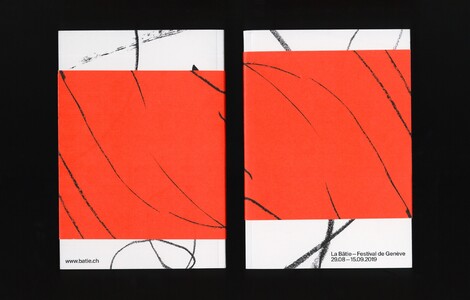

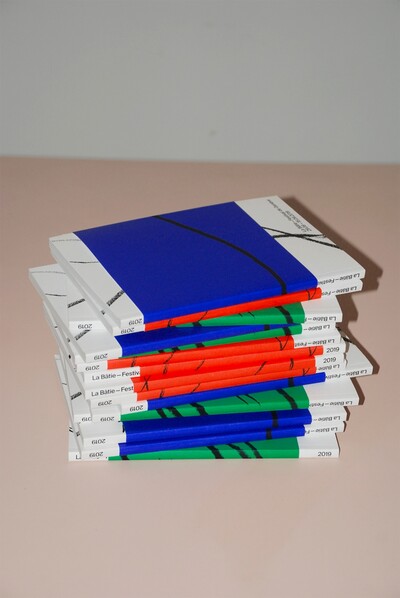

I think it worked out pretty well for them, because they really needed it. The first year was well received, and the following year we worked on movements and rhythm. We asked the dancers featured on the following season’s program to move the way they usually do — except their hands and feet were equipped with felt pens, with pencils, sponges soaked in ink, etc. While dancing they created an enormous amount of traces on the white paper. We used those rhythms to create the designs. We used them on the posters and all the other communication tools. So it was the performers themselves who created the festival’s visual identity. La Bâtie team was extremely supportive, which was great. The more people trust you, the more a project is successful.

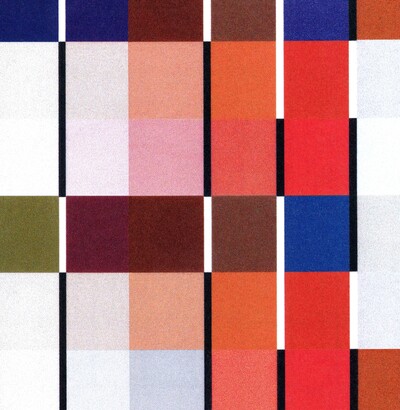

La Bâtie-Festival 2019

La Bâtie-Festival 2019

La Bâtie-Festival 2019

La Bâtie-Festival 2019

Are there certain projects that you would have preferred to develop a little more?

Baleapop, the festival in Basque country, it ended — it was their tenth year, but still… you want projects like that to continue, where you get to do exactly what you want, you have a carte blanche… Their trust in our art direction was so great that we became friends. It was a dream project. When it stopped, Tools picked up the slack.

Do you ever forget that you’re actually working?

When you do Tools, or Baleapop, or even La Bâtie, when people trust you and you bust your tail, it’s no longer work. When the clients don’t listen to what you say and want to do something different and you’re constantly forced to fight them without ever getting to do what you want to do, then it’s work!

Tools Magazine

What part does typography play in your work as a designer?

Luckily for me I know how to put together a good team! Malou and I are very complementary. She is super good at grids and typography, she has the knowledge… She digs up old things a little here and there and always comes up with the nugget, that’s how it went down with Tools… She always aces it. She understands the general identity and how I want to go about the art direction and she always comes up with the right thing.

You don’t find it taboo to not know how to do something and just hiring the right people ?

I know I’m good at certain things and suck at others. When you start out at school you get the impression that you’re going to have to know everything. But it’s not true: you don’t do everything well. There was also the idea that once you get out of school you’re a graphic designer, you can create models, etc. The profession has evolved a whole lot, and so have we. Now we do more art direction than graphic design. I like to do art direction and hire a good team of designers.

Tools Magazine, photography by Jean Marie Binet and set design by Cesar Sebastien

Do you believe there’s a method for finding fresh references and stimulating your creativity, or is it a lifestyle?

I love going to the library and finding old references. It’s the same as everything, when you’re talking about knowledge, craftsmanship, objects… I spend hours there! Last winter I visited every library in Paris fifteen times looking for ways to move forward. To find a thing no one has ever seen, a great photograph from the nineties, or the seventies… It’s amazing.

For example, I adore the BPI, at the Pompidou Center. You access things directly. I scan everything…I bring my own scanner! I’m pretty sure it’s not against the rules… is it ? If they read this I might get in trouble… There is also Forney. They have lots of stuff about craftsmanship. But at Forney you can’t scan, it makes too much noise… Or else the library at the Musée des Arts Déco, though you have to reserve things ahead. My dream would be to explore their cellar. They have tons of stuff.

Baleapop 8, Totems before being painted for the festival’s scenography

Baleapop 8

Do you think you’ll still be this creative in ten, fifteen, or twenty years?

I think so, even though in my opinion your work ends up being passé after a while. Seeing as I have to be creative, I might end up doing something else. I might end up going out to live in the country and becoming a handicrafts worker… But I always try to look at projects through the lens of: “How is this thing going to age?” Sometimes you give in because you know clients just want something fashionable, or pretty, or zippy, other times you think things might last a little longer.

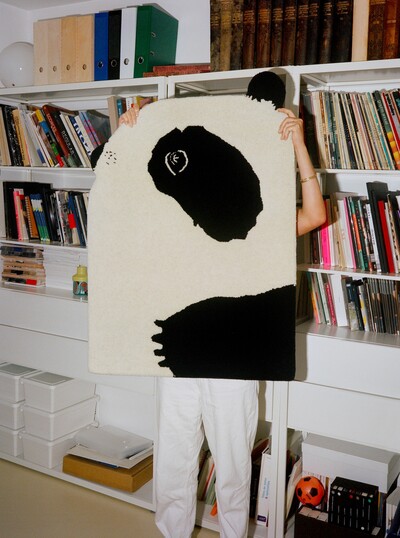

Panda edited by Element Optimal, danish contemporary design brand.

Panda edited by Element Optimal, danish contemporary design brand.

What has changed between when you started out and now that you’re going to be turning thirty-five?

The profession. At the time, when you got out of school you were a graphic designer… Now they study art direction in school. That was not the case in my time. You did layouts and typography but you didn’t necessarily think about the overall image and its applications. At the very beginning we made patterns that we applied to all sorts of media, we worked with photographers… Now none of what we do resembles that at all. And I must say I like it a whole lot better.

Artwork for Odei, Andde, Conceptual album made during an Artistic Research Residency at IRCAM, Paris.

Artwork for Odei, Andde, Conceptual album made during an Artistic Research Residency at IRCAM, Paris.

Could you tell us about the things that worked right from the start and the things that you would have liked to do differently?

From 2012 to 2014 we met loads of people at the Ateliers de Paris. Everybody had their workshop going but every day at noon you talked to people, everybody was developing their projects: so we began building our network. Thanks to this we were able to collaborate with loads of people. We got work straight away, and super interesting projects, too.

After that initial flurry we went through a dry spell, and there was one year, I think it was 2016, when our turnover was just awful — our prospecting was getting us nowhere, I remember, and we were freaking out. And then we met you, Bildung… I’m not sure if I’m supposed to mention this or not (laughs)

No reason not to be transparent, keep explaining please!

Something happened. We learned to structure: we created our company, whereas up until then we had been kind of freelancing; we learned how to prospect, we were introduced to some people, and things took off again. We became more professional. I think we became more adult, and we recruited people to work with us. We should have done that a lot earlier, but they don’t teach you that at school. I think we wasted some time, though not more than two or three years… At the same time it’s also a good thing to trip up; it allows you to reboot. In the end it might not be a waste of time. It was a bit tough, though.

Developments Sketch by Clémentine Berry

What would you have done differently?

Invoicing: I didn’t charge enough. We undervalued ourselves enormously. We used to say to our mates: “So how much did they give you to make that?” In fact, to be perfectly honest, we made just enough to pay the rent. We used to talk about it, but since we were all undervalued it didn’t really help much… I think it’s the same for everyone who’s just gotten out of school. They don’t teach you the business aspect, even though it’s part of your job.

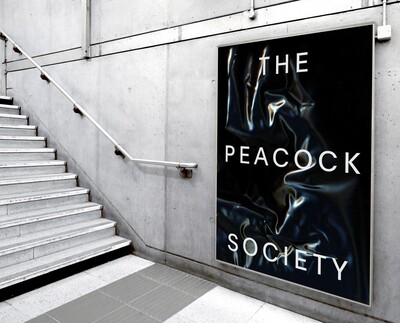

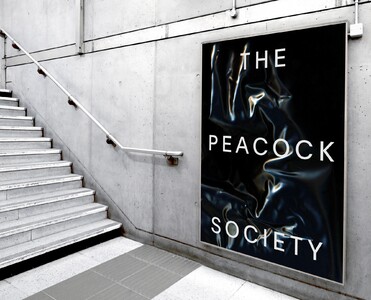

The Peacock Society festival

What more would you have liked to know when you were starting out?

There’s one thing that comes with age and wisdom, and that’s self-confidence. In the beginning, I was intimidated around clients. That state of affairs lasted a long time. Now they trust us more and it’s easier to get our ideas across. Well, it doesn’t work systematically and sometimes you have to know when to throw in the towel. But still, there are more and more projects that come out that I am proud to show.

What do you like about design and architecture today?

The ultra-precise know-how that is involved; the things that only the oldsters know how to do. The immaterial legacy as I believe it is called. It’s super important to go in search of that and learn from it. When the old dude tells you about a thing only he knows how to do it’s insane. You think it’s imperative that someone should follow in his footsteps, otherwise it’s over. Now I’m also interested in the hyper modern technologies that are happening now… The makers for example, 3D printing… The range is amazingly vast!

Tools Magazine

And in terms of images? Anything going on right now that you like?

In art direction the people I tend to like often have old school references, like me. But there’s a guy, Esteban Diacono, who makes characters move in 3D, it’s a bit… syrupy, gross. I’m fascinated by that stuff, I can look at it for hours.

How would you define art direction today?

I think you’re a good art director when you bring together people with different skill sets who perform well and that you manage the whole team in such a way as to create the image that is as close as possible to what you want to say about your brand or your campaign.

How have your clients changed? Between your first clients and your current clientele?

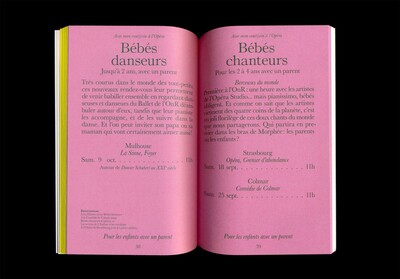

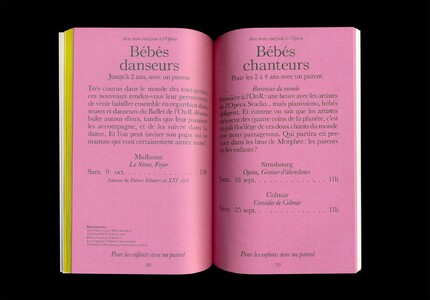

You start out with little projects, and it takes off from there. And competitions. We just won the Opéra national du Rhin. It’s a three-year project. Which is super nice, a really enjoyable collaboration.

Since their new director arrived, the dynamics of the Opera have changed. The communication is based on storytelling. The first year will be a story that brings people together, the following year — the one we’re working on now — will be stories that are therapeutic, and the last year will be something else. We came up with an identity based on stories, books, mainly paperbacks and their imaginative mystique. All of our communication tools will hinge on those references. We’re producing a collection of books for each tool and we’re working with artists (a new one each year) to illustrate the shows and the programs. This year it’s Maïté Grandjouan, an artist who studied at the Arts Déco Strasbourg. We wanted to begin with someone who had studied locally. We’re currently thinking about next year.

Opéra National du Rhin 21-22

Opéra National du Rhin 21-22

Do you have a plan for the three coming years, or until 2030?

To develop Tools, because there are lots of things to be done. And get projects for Twice, in the same vein design-wise, and in terms of craftsmanship…

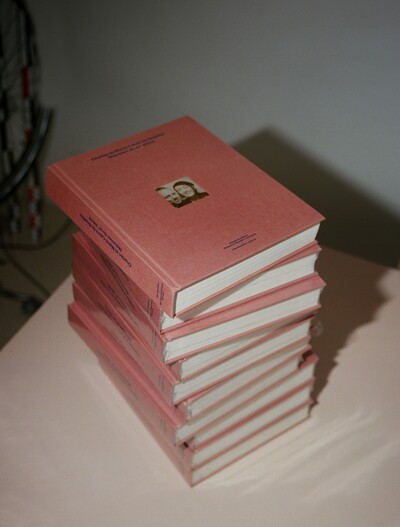

How do you meet your clients?

Often through word-of-mouth, thanks to a project that was successful, or because they’ve seen other projects of ours. Sometimes we do pitches like the Strasbourg Opera. But only when we find the project interesting; otherwise we don’t do them. When we really feel like doing one, we do it. And sometimes we reach them by communicating, such as with Tools. It’s practical: you send it to people you would like to work with, and it’s easier to take that first step by sending them an object. The book we did on Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles for example, we sent out about fifteen of them I think. And it got us jobs.

On the other hand, I don’t tend to use social events. If I go to an art opening, it’s to see friends. I don’t go thinking: “Oh, I might run into so and so.” I just can’t think along those lines. I probably should do, but I don’t.

Sending books or magazines remains the best prospecting tool for me. Tools is a big investment for the studio, but I think we’ll earn back our investment through large-scale projects that come out of Tools.

Charles et Marie-Laure de Noailles, Mécènes du XXe siècle book, Villa Noailles

You mentioned you won a few good projects through competitions, what’s your view on them?

I don’t really like doing them because I find that what is interesting is to talk with the client. And go search among the references, and immerse oneself in the project a hundred percent. When you’re competing, you can’t do that. Clients don’t have the time to see you. To come up with something good for a competition is really tough. You never go far enough. You can easily fall prey to an overview and end up with something that might look nice but that doesn’t cohere to what you want to say. It’s really a drag.

But for Strasbourg, for example we did it because we loved the subject, it was well conceived, there was a foundation; it wasn’t just “Create an identity.” It’s a special type, we had to think about it ahead of time, and we did it until the end. I think we managed to head in the direction they were hoping we’d take. La Bâtie was also a competition and we said: “We won’t do any creative work without exploring your archives.” And so we went over there.

So we did all right but I think we got a little lucky. La Bâtie, we had to fight to go over there, meet the people and see their archives. We spent a day in their cellar, where they had all the photographs. The opera, we had a good brief. In the other competitions we did it never worked out because we hadn’t done enough homework about the subject. That’s really disappointing.

When you introduce yourself to a new client or present your work in a competition, how do you feel?

I’m always stressed out, though it depends on the people. When things are laid back it goes really well, but sometimes if people are a little formal, it’s more difficult. I try to be nice, to be myself. But frankly it is difficult.

When I present graphic solutions, I prepare intensively. When I present the work of Twice or Tools, it’s pretty fluid since I’m on familiar ground.

Tools Magazine, Photography by Matthieu Lavanchy and set design by Romain Lenancker

Is it hard to manage a client over time?

No, because in general when things last it’s because everything is on the up and up. I prefer working with people over several years, because during the first year you try to understand how they work, the second year you’ve got it down, things are moving forward, and then the third year the confidence level is high and everything is clicking. On the other hand, when you create identities for festivals or opera seasons, it’s hard to stay on the ball…

We had immediately mapped out La Bâtie over a three-year period, thinking: “First we work on the body because we need to shine a light on the body. Then we’ll work on movement, with the designs created by the dancers. Then we’ll work on rhythm.” We shuffled images and cut them up. When speaking with the team about how we planned to proceed, we had already presented to them the three-year plan and I think that was important. As far as the Strasbourg Opera goes, we haven’t yet chosen the illustrators, but I know each year’s choice will be based on the given identity, and that will renew the visuals somewhat. With Baleapop, we had a different theme each year, so with some soul-searching we could rebuild the entire identity according to the theme.

How do you go about transitioning from one subject to the next, from one project to another?

My greatest quality is efficiency. When I finish something I already know what I’m going to do next. Which is something I learned from my farmer parents. My uncle always used to say: “Once one job is finished you should already know what the next one is going to be.” This helps you move forward, be efficient, produce. I never lost that state of mind. So I’m never inactive. I have loads of defects, but that right there is my quality.

Sketch by Clémentine Berry

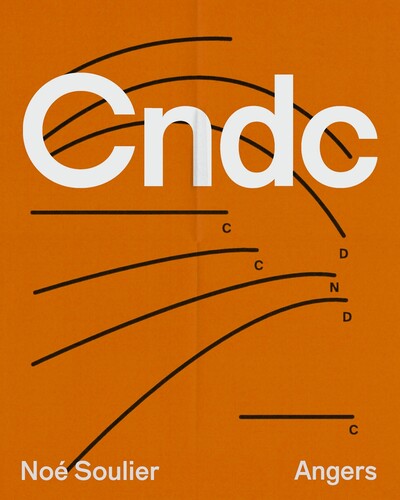

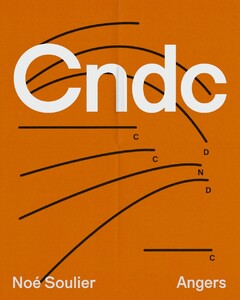

Cndc-Angers

How do you feel about collaborative efforts?

I love them. When you’re an art director you collaborate with loads of people. When you do photo shoots you collaborate with a photographer and set designers, and I love that. Seeking out and utilizing each person’s expertise — that’s what I prefer. It’s often word-of-mouth. I trust people’s recommendations, then I keep an eye on the work as it is done. Sometimes, afterwards you think you should have used someone with more experience, or that you won’t work with that person again, but that’s exactly how you gain experience.

Cndc-Angers

How does a graphic designer or artistic director go about developing nowadays?

You have to find projects in which you are given free rein, that show off your skills in that you were able to do exactly what you wanted.

Cndc-Angers

Cndc-Angers

How about collaborations with other art directors?

I’ve never tried that, but I think it could be pretty cool. Though you have to be sure to find someone who’s on the same page as you.

Do you believe one learns things in agencies? When you get out of school your choices are usually to freelance, to create your own company, or go work for a marketing or an ad agency.

I’ve never done that. Having never worked for an agency, I can perhaps just say that I believe the future lies in the small studios rather than the big agencies. Clients come directly to us much more often these days because the agencies take an enormous cut. They have a lot of employees to pay. We’re very open to listening to people, we’re a small company, so the client doesn’t talk to the assistant or whatever. We’re much more able to come up with what they want. You take a big agency campaign budget, you divide that by ten studios and everybody’s happy without being underpaid.

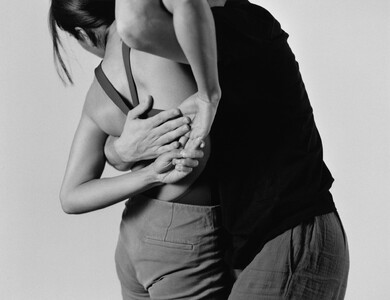

Pierre Guariche, Sammode

Do you see a difference between people just starting out and people your age?

I know that people aren’t trained the same way nowadays; nowadays in certain schools people graduate as an art director and not a graphic designer. The young generation masters all kinds of things; they know how to create an identity using all the communication tools, they know motion design, web design, they know about font design, or 3D. The thing is, in my opinion, moving forward you need to specialize in something; it’s hard to be good at everything.

When we were at school, the first years we made everything by hand. That’s also the way the profession evolves. It’s par for the course.

Do you feel like they have a better knowledge of entrepreneurship and business?

I think they’re ambitious… and thanks to Instagram they see so many studios that in my opinion they’re much more focused on a future as entrepreneur or in any case as business executives. Whereas me, for example, at the time, when I was coming out of school I went looking for a long-term contract with some company.

On the other hand, they seem to have a limited concentration span. There’s one thing they really need to learn, that is to dig deep in order to find the rare gem, the right reference, the good idea. They really come from the culture of Instagram, and Pinterest. That approach can be successful but I think it’s important to have both. Another important thing about this new generation, they seem to be concerned by environmental issues. Even in architecture, in design. Obviously, I find this very important myself. In Tools we usually feature an article about plastic, we talk about its history, but we don’t just say positive things about it because plastic obviously has a negative side.

Tools Magazine

Are you active in your approach to this subject, for example in your choice of printers, paper, distribution models?

We work a lot with recycled paper… Now everything has a label. People pay close attention. The same goes with ink. In the 1970s books were super gorgeous with very dense colors, but you can’t use that kind of ink nowadays.

Do you think that Covid has accentuated this in any way?

I was in the country during the pandemic, and I said to myself: “What the fuck are we doing? Let’s go uncover old crafts that pollute less; how people did things before?” etc.. That kind of thinking is in part how Tools came to be.

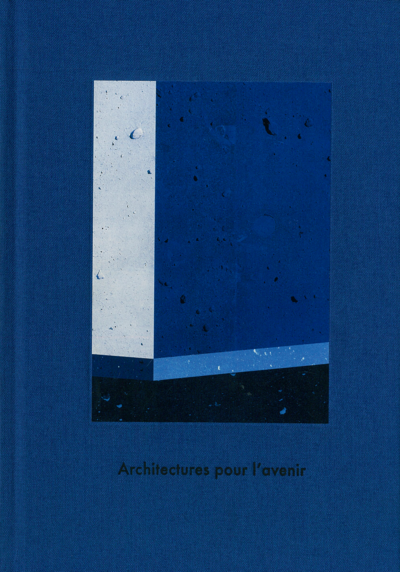

Villa Noailles architecture book

If you had to practice your profession at another time in history?

I’d like to experience the early years of the computer. I would have liked to do page layouts and projects by hand. Just to see when they wedged their text for example. It was another profession and I would have liked to be able to test that. But I also like the current period. You can do all kinds of things.

Is there a book, a movie, a work of art or any other artistic references that helped you gain a better grasp of your profession?

The Whole Earth Catalog. It’s a magazine from the 1970s that lists all the books of craftsmanship and a whole lot of other things. Sophie Tajan turned me onto it. There are loads of issues. They broadened their scope with reference works on any kind of field you might be interested in: basketwork and plenty of other things. Even graphically, in terms of the typography you can see the connection in the Tools page layout.

Where do you see yourself in ten or fifteen years?

It depends on how life plays itself out. At one point maybe everything will blow up. I know I’m rather pessimistic about all that but at the same time I’d find it kind of cool. The planet is going to say: “You’re fucking up, game over.” I can very well see myself weaving stuff in the country. Living in a commune with friends. If everything comes to an end, that’s what I’ll do directly. If everything does not come to an end, well, I’ll continue doing what I’m doing right now. Otherwise I’d fear I was missing out. But I need to do things. Maybe I’ll get into handicrafts: I don’t know. I think I wouldn’t be unhappy doing that because once you know how to carve wood you can go on doing it forever.

Retiens la nuit, catalogue d’exposition, galerie Rabouan Moussion