Hi, could you please introduce yourself?

I’m Andrea Trimarchi. I’m the co-founder of Formafantasma, a design studio based in Rotterdam and Milan. Actually, Milan and Rotterdam.

Simone Farresin and Andrea Trimarchi, FormaFantasma founders.

Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Why the specific order? Why Milan first?

Well because we were based in Holland for 14 years. And this year we came back to Milan where we have the main office, so the Rotterdam one is a branch now.

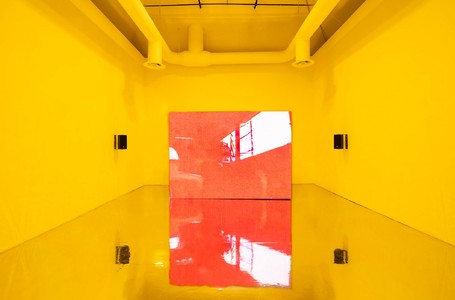

Formafantasma’s Milan office

Formafantasma’s Milan office

Formafantasma’s Milan office

Formafantasma’s Milan office

How do you usually present Formafantasma, your design practice?

First of all, we don’t call ourselves a studio, but a practice, as you just mentioned, and we say that it’s basically a design research practice. We work at the intersection between a commercial and a research-based approach. The majority of the work we do touches on ecological concerns. We can’t do 100% of what we want all the time, but of course, we try to view all the work we do with some ethical perspective.

It’s mid-December now, what’s your current state of mind?

Really tired. Really looking forward to having a long holiday. Actually, we can’t wait. But it’s also positive. It was a very good year, I have to say, since we also moved back to Italy. We really wanted to come back and root ourselves back in Italy. Work is going very well, our team has grown a lot, so it was a very good year, but indeed, we are very tired.

Formafantasma’s Milan office

You and Simone founded the practice… How did you two meet? During your studies?

It’s kind of an interesting story because both me and Simone, well, we are Italian. We studied in Florence at ISIA. It was the first school that was born after the economic boom in the sixties and was founded by the Archizoom and all the designers that were around the radical movement in Italy. But we were in two different years, I am actually younger than Simone. That’s when I was about to graduate, and we started hanging out. Because we are a couple, we are together, our love story started before our work affair… But after a couple of months, we started talking about work and we were really passionate about design, we were collaborating on design school projects, and we decided to move to Holland together and apply with only one portfolio to the Design Academy Eindhoven. We got there with this idea already in mind of working on a drawer with the name Formafantasma, and we sent only one portfolio to them. And Gijs Bakker, who, at that time, was the head of the department which was called IM, and who was the founder of Droog Design, accepted us as a duo. And we’ve worked together ever since. So let’s say that started more as a love story. We are still in love and we also have this work together.

Why did you choose the Design Academy Eindhoven specifically at the time?

When we started it was 2007. Of course, the Internet was there but you didn’t have all the blogs and magazines talking about design the way they do today. And we were much more focused on our research. Of course, we were going to the Salone del Mobile every year and the most progressive school at the time was the Design Academy. We were going there to look at what the Dutch designers were doing at the time. Droog Design was in full bloom and at the Design Academy at that time there was Li Edelkoort, it was very interesting for young designers. When we applied to Design Academy, we were looking for a place where our generation was represented. In Italy, we have a long history linked to design, but most of the time it is highly related to the maestros and not so much to the new generation. And in Holland, we saw something that was not happening anymore in Italy, just new and younger people. Of course, we were also very interested in the conceptual approach that was initiated by Droog Design and then taken over by the majority of the Dutch designers at that time.

How did you come to the decision to found your own studio after studying?

Before!

So what was your plan when you graduated? What was your intuition about your development then?

Even when we came to Holland, we were already so driven, we knew what we wanted. Also, in terms of the themes we were developing within the Design Academy, they were bold and they still are. So we were looking at the complexity of national identity and race, especially in design, craft, tradition, and method. And we were looking towards ecology and practising a lot of material experimentation, so during those two years, we could already experiment with some of the topics that became the DNA of the studio.

And Eindhoven was a perfect moment and a perfect place to start. You know, it’s a super ugly city. It was in a derelict state from the huge industrial production of Philips that left the country after the war and then left Eindhoven full of industrial debris, so a huge building was left alone, and the city was almost without identity. Eindhoven really reinvented itself thanks to design. At the time, it was fantastic. You could rent a space for €100 and there was a lot of financial help given from the government to designers. In the beginning, it was this perfect space of silence. We didn’t have any Michelangelo or Donatello around, we had super ugly brutalist buildings and almost no restaurants, no bars, so you could concentrate solely on design and your practice. Then of course, it was also very good to move away from there, because the problem with Eindhoven, of course, is that you get very comfortable. You don’t pay any rent, and there is a lot of support from the government, but to make that into a real business is a different story. So after a couple of years, we moved to Amsterdam. It’s a much more expensive city and now we are in Milan, which, of course, is also a city with a strong relationship to design, production, and fashion. We also grew very gradually.

It seems you never dropped research, you kept on exploring. Was it when you moved to Amsterdam that you decided, okay, we also need to have a stronger relationship with the industry and to have some products edited? How did it happen?

From the beginning, we were trained as product designers in Italy, so our interest in product design and industrial design has been always there. Of course, as you know, when you start, it’s also very difficult to work with companies. You need to grow up a bit more to be noticed. I have to say, it was quite quick: two years after we graduated we started working with big brands. I remember at the time we worked with Fendi, we had the connection with Flos. We already had the first links within the industry, but it took several more years to really turn it into a plan for the studio. Now we have a very good balance with our research projects. They are commissioned by institutions that most of the time don’t have a very big budget, but on the other side, we have projects that can allow us also to take on more research. In the design landscape, we are quite particular as a studio because we can merge both sides. We have quite an ambiguous practice and we like that because we are not only preaching, we are also dealing with certain issues, and we are also trying, as best as we can, to bring some narrative from our research into the more commercial projects.

WireLine, Flos, Villa Ottolenghi, 2019

WireLine, Flos, Villa Ottolenghi, 2019

WireLine, Flos, Villa Ottolenghi, 2019

How have you maintained that balance over the years and have you noticed any patterns?

At the beginning, it was very natural. Now we really have to make a lot of choices. We are also in a period where we are saying no to a lot of projects. We pay attention because it’s also very easy, especially now that we have much more visibility, to get really drawn into just the commercial approach and leave behind the other part, which we think is the strength of the studio. We also see that this is a really perfect time because the companies we are working with at the moment—I would say more than 30 projects—are not all visible. They are approaching us now because what we do is clear, and our themes are relevant. Ten years ago, of course, everybody was already thinking about ecology, but now ecology is the topic, inclusivity is the topic, diversity is the topic. Ten years ago, it was something that was maybe more present in other sectors, I would say more in food, for example. If you think about ecology related to food, it has been there since the nineties. But when it comes to design, let’s say that… Also art, you know, like in any case, artists with a much more strong ecological focus have been there for years, whereas in design, let’s say it’s been a bit left behind. Now it’s the pattern that we see, it’s that, you know, most of the companies, whether it be out of a greenwashing attitude or a true belief in it, they are really all going in that direction. It’s quite comforting.

Is there anything you would change in the way you’ve developed?

No, I have to say. I don’t think so. I think what we need more now—because now there are 12 of us—is to have more structure. And it’s something that we are trying to build with this very horizontal approach. We don’t have specific roles in the studio. But when you start to have a lot of projects running simultaneously, it’s more complicated. So probably in the structure, I would change something, but not in how we work. We are very happy about that.

If you go back to creativity, can you remember what your creative references were when you were studying back in Eindhoven? And have you got any new ones now?

It’s very strange. We had a lot of references back then. Now, it’s not the case, or not in design. At that time we were looking at the work of Hella Jongerius, who’s still a very important person and figure for us. Or the work of artists such as Philippe Parreno or other practitioners who were very important to us. Enzo Mari, when he was still alive. We don’t have references anymore. And I think it’s also because we are in a stage of our life in which we are probably becoming the reference for somebody else. Of course, I admire the work of the great designers like Konstantin Grcic or others, but I would say that in the past I could refer to some of the maestros as heroes, kind of. Now, the more we are going ahead, the more we contextualize those people in history and we think that maybe we are at this particular moment trying to build a new narrative in design. Of course, there are artists that we love, musicians that we admire, and creators that we think are striking. But when I think about designers as a profession, no. Not particularly.

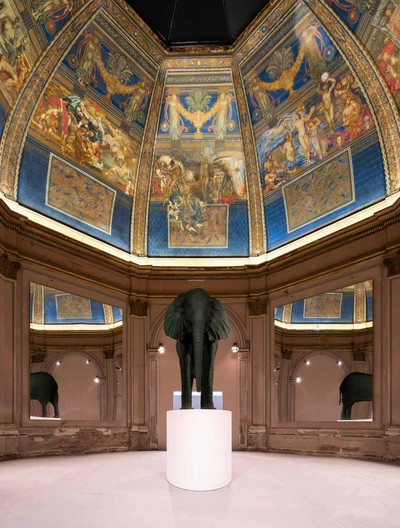

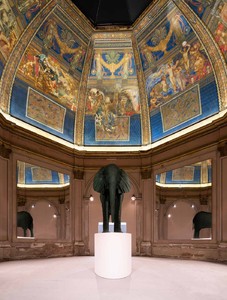

Palazzo Delle Esposizioni

Palazzo Delle Esposizioni

You seem to have had a really strong year in terms of exhibitions and cultural projects. You mentioned having a horizontal structure. How did you find the time and creative resources for all those projects?

Yeah. Wow. Difficult. Time is the most difficult part, and that’s why I also mentioned before that we need to structure more because we are in this in-between state, and we also do a lot of bureaucratic bullshit that we hate. And the creative part is getting less and less pertinent. But we are trying to change that. I’m not going to bore you with how we are thinking of structuring the studio, but in the future, it will be different. We do have a very good team of people. They are almost all from the design and architecture world, but they are all in research and have different approaches. We have some people working more on exhibition design and others who are more into the cultural side, so they’re doing more of the research. So we have different characters, and we play around that.

How many people currently between the two cities?

Between the two practices, 13.

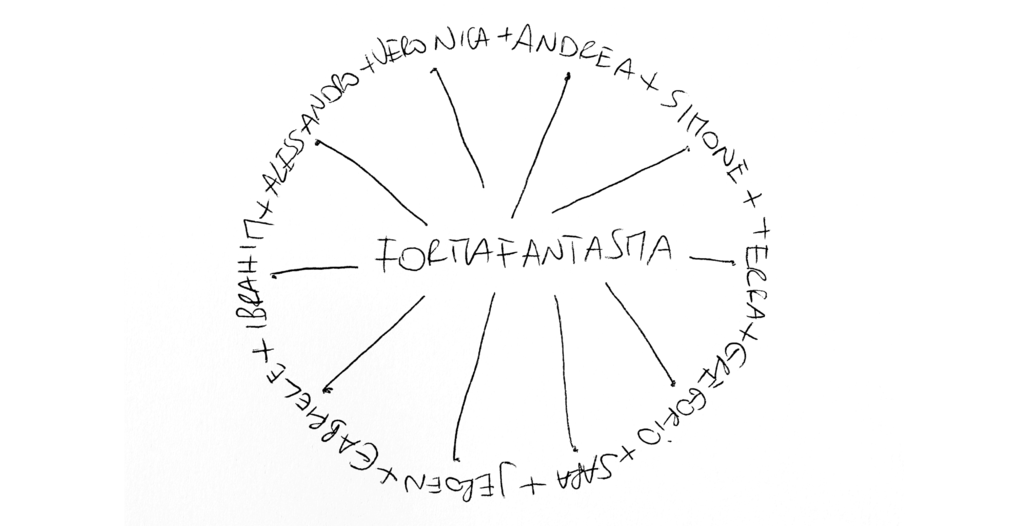

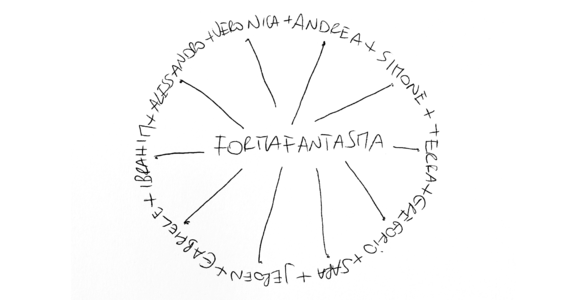

Sketch by Formafantasma

How do you manage? Is that what is eating into your creative time? Having to manage the two cities and those people?

Well, in Rotterdam, we do have a senior who is dealing with only one person there at the moment. And he is also our oldest collaborator, we really trust each other. His name is Jeroen Van De Gruiter. And here in Milan, if we need to divide the roles a bit, I’m the one who is dealing more with the bureaucratic and administrative side and time management, and Simone, he’s the one who writes more. But when it comes to the creative process, we are quite equal. We divide the tasks a bit, but for the creative part, it’s almost the same. And we do a lot of sessions with guys in the studio. We talk and we review and since some of them have been working with us for a couple of years, they already are more experienced and know how to move the work forward.

I’m interested in those developments in terms of structure, are you trying to bring in people who will handle mostly the administrative and project management side of things?

Correct. That’s what we are trying to do. We were trying recently with a person who was supposed to work more the way I had, both for administrative matters and projects. But then we realised that the best solution for us might be to have a PA and to empower some of the people working in the studio to create teams without fixed roles or hierarchy and also to have a point person for each project. We are working on this collectively to try to determine how to set our practice up in a way that avoids it becoming hierarchical.

The Milk Of Dreams, 59th International Art Exhibition at la Biennale di Venezia

You mentioned that you’ve got this horizontal culture at your studio. How did you handle that? Did that grow organically? Because I imagine you were not trained in management at Eindhoven, right?

Zero! [laughing] We grew little by little. We have also been teaching for many years and dealing with this in the Academy as we are also the heads of a department, so we know how to do very quick reviews. When you work with students, in a day you need to talk with twenty people, working on twenty different projects. You need to have an opinion and potentially shift the project. We are almost like an art director and the other people are developing their project.

How do you take decisions? Is that you and Simone?

Mostly, yes. That part is not very horizontal [laughing].

When you have two cities, 13 people, you have to take a lot of decisions each day. How does it work? Do you take some time to debate and then decide or is it more organic?

We have a very clear agenda. And on days that we don’t travel, we talk with everybody. And the good thing now is that we don’t have all our deadlines at the same time. At the beginning of our practice, we were all the time working towards Salone del Mobile, now we have many different projects. We also work with curatorial matters, exhibition design, consultancies. We do have scheduled deadlines and it’s a bit easier to build the workflow than before when everything was really concentrated around one deadline.

Excinere collection in collaboration with Dzek, 2019

Excinere collection in collaboration with Dzek, 2019

Excinere collection in collaboration with Dzek, 2019

You graduated in 2009. It’s a great thing to have become internationally acclaimed within what was, in hindsight, quite a short time frame in terms of design and designers’ timelines. Were there any significant turning points? Any crucial moments?

Yes. I mean, definitely our graduation, that was for sure the first one. I think we also met some of the people who were very instrumental later in our career or immediately after, like, for instance, Libby Sellers, who had a progressive and radical gallery in London that she closed a couple of years ago. That connected us to, for reference, people like Alice Rawsthorn or Paola Antonelli who have been very supportive since the beginning.

The second important moment for sure was when we presented Botanica in Milan in 2011, it was a project about plastic that came from natural resources, like animal derivatives or vegetable derivatives. That work was very important because it has been acquired by practically all the museums from the MoMA, Victoria and Albert, to the Metropolitan… You name it.

And then another important moment was when we did the lava project. It was a research project about material that migrated into a more commercial project having to do with tiles and lava tiles.

When we started a collaboration with Flos, that was also quite important because it was the moment in which we made the change from not only working with galleries and institutions but also working with production companies.

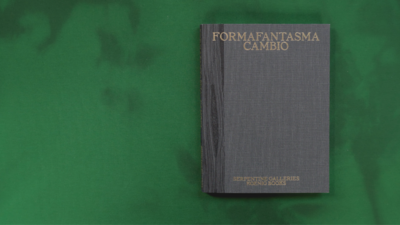

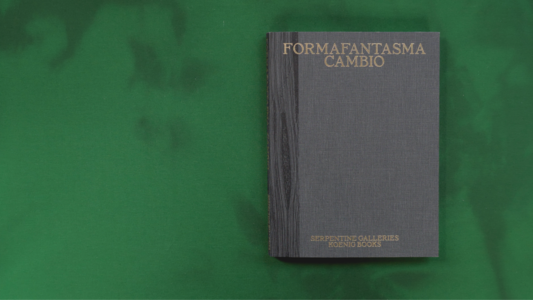

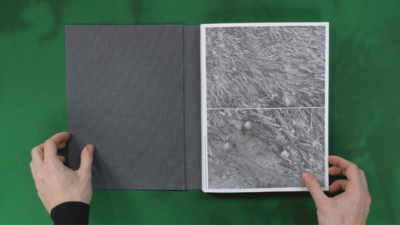

And then probably the latest one is when we presented Cambio at the Serpentine Gallery. Serpentine is a very important gallery directed by Hans Ulrich Obrist. They work mainly with art, so it was a very important exhibition because it was putting design at the centre in terms of themes and approach.

Visual essay, Cambio exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, 2020

Visual essay, Cambio exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, 2020

Visual essay, Cambio exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, 2020

You mentioned you had some creative references when you were studying. Did you have any strategic ones in terms of developments? Because it’s really tough to do as many things as you do, maintaining the balance and being able to be in Serpentine and having some products edited with Flos. So were there any strategic references or models?

No, that’s also very difficult. We think about that all the time, who is our reference? I think for certain moments it was definitely Hella Jongerius for the integrity and the work. She has been working consistently and very well with a lot of big companies, such as Vitra. She is also very interested in this more non-commercial approach and making exhibition and curatorial products. But then we have very different references for the different parts of the work we do. I mean, even if he’s an old maestro, Mari is still one of the most important references, again, because of his integrity, and the narrative he brought into the discipline. He was very interested in social issues, and he was trying all the time to solve that in the production process, so for sure, he was a very important reference too, but it’s very difficult to find contemporary references…

The Milk Of Dreams, 59th International Art Exhibition at la Biennale di Venezia

As you mentioned with the ecological challenges and sustainability issues, it’s also a very particular time for designers especially when you’ve also got art galleries interested in designers. Today, what do you and Simone consider essential in your next developments or phases?

Finding interesting clients that understand our work, ask the right questions, and are ready to change the brief. Sometimes—and, fortunately, it’s happening less and less—the client just comes because of the hype or what we can bring in terms of visibility. And they really don’t get what we do. But things are changing, as I said before, so for the future, my only wish is to work with enlightened partners. Something that is also happening more and more is that we are asked to make products that are not related only to design. And that is also very interesting: how to apply this intelligence or intelligent thinking that we have with respect to design in the context of other disciplines.

The Milk Of Dreams, 59th International Art Exhibition at la Biennale di Venezia

And how do you get to meet those interesting prospects and clients?

The interesting thing is that they come to us. That’s also the best way of doing things because when people come to you, maybe it’s because they understand what you do.

I have to say, we never look for jobs. Since we started. I don’t know how we survived. So far, it has worked out.

WireLine, Flos, 2019

You mentioned coming back to Milan. It’s a strategic decision. How did you discuss that and why was it necessary at this stage?

The first reason was family. Both our families are here in Italy. And in terms of business, as much as I like Amsterdam, it’s a city that operates only on services. There’s almost no kind of production, there are no big brands. And for the work we do, Milan is the best place. I mean, it could be here, in London, or in Paris. When we were thinking about moving back, we strongly considered different cities. But if you want to establish and expand and strengthen your position, I think you need to be in a city where things happen. Milan is good, you can go to an opening and meet somebody very interesting and start a relationship right then and there. We see it. There is also a huge fashion industry here. In the last two months, we have been meeting with practically all the CEOs of all those companies, one way or another. Not only for work, sometimes it was only because we were at a dinner or something, so it’s also very easy to stumble into jobs.

That’s a certain kind of prospection, isn’t it? Meeting all those people outside of work, not asking for an appointment, but developing that network.

It’s a way of doing it, even if I have to say, I do much prefer when people come to the studio, or we go to them and can explain what we do. Because on other occasions it can end up being superficial. But it’s a very good way to meet people for sure.

Italy is a very specific place for design, as there are a lot of great designers, and editors obviously, and there are still a lot of production facilities. Was that one of the reasons to relocate, to be in more direct contact?

Not necessarily, but two areas are definitely the most important for design: either the Northern European countries—Sweden, Denmark—or Italy. And in any case, the majority of production, even for the Northern European brands, happens in Italy, so it’s very easy to meet clients. You take a car and go to Brianza, where the majority of companies are located, and it’s very easy from Milan. It’s also much less time-consuming. And of course, you also have more possibilities for production. It’s a very good country for producing, especially when it comes to objects.

Nude

Nude

Another important part of the job is to handle your communication. And we’ve noticed—I don’t know how long ago exactly—that you changed your website…

One year ago, more or less.

I was impressed with the radical approach to a design practice website. How did you think of that? How did you take that decision?

When we were thinking about redoing the website, we approached it as a project. You could really easily think about doing a portfolio, but we thought about the infrastructure of the Internet and of course also the way a website is developed. We were already doing research into electronics and a previous project we did was about electronic waste. We really had to think about what it means to produce a website nowadays, working through images, maybe images that you are not even looking for. Most of the time, when I visit a website, I want to understand what or who I have in front of me and maybe even see a brief word saying, “I’m this.” And then when you go more deeply into the site, you discover things.

The page that consumes the most energy is the homepage, especially those new websites that have videos and a lot of images. And we really wanted to go beyond that because what we do here is really about the content, so we wanted to remove as many images as possible at the beginning. Then of course when you click on the project, you have a lot of information, a lot of images, but then you need to choose. And then of course, we implemented a lot of small details, like the black background which, especially on phones, consumes much less energy than a white background, and other really small other details. Our website consumes 80% or even less energy than a normal website of similar structure and content.

You’ve got this specific positioning between art, design, research… And having people go through the categories like a thesis summary is a message in and of itself. I had not thought about the energy savings. I thought you wanted people to read before looking at images. And I found it really clever and really fitting, your research DNA. So, how do you take those communication decisions? How do you handle the Instagram? How do you decide that?

We do everything internally. We don’t have a PR company, we never have. We do collaborate for certain projects with a PR company, one that is based in Milan, she has been following us since the beginning, but we really do everything internally, all the content we produce. We are real maniacs.

Mondo Reale, Fondation Cartier 2022

Mondo Reale, Fondation Cartier 2022

Is it also because you want to be methodical with regard to the words being used to talk about your work…?

Exactly. We don’t trust how people talk about our work. I mean, there are of course very good writers, but it depends on the magazine. Sometimes we see copying and pasting from the press release. It’s very important how you portray yourself. And if you check online, you know that, in any case, 90% of the facts are provided by us, so it’s better to write a good text and to communicate as well as possible.

We briefly mentioned Instagram. What’s your view on Instagram, especially nowadays?

It’s a very, very good tool. It depends, of course, on how you use it. For us, Instagram is, at times, a tool to show our research. For instance, at the moment, we’re working on this large project for Norway about wool. We are starting to show pieces of the research we are doing within the studio. And at other times, it becomes much more of a direct marketing tool. During Salone del Mobile, you know, we show some photos of the installation or the things we do. But I think it’s a very useful tool. It’s the best one, I have to say, or at least it’s the one that we use the best, I think.

Moving on to more generic questions, how would you describe the current design scene?

Um, well, it depends. When you talk about the current design scene, there are different design scenes. There is the more well-known one, the more established one that is very traditional, and that I personally find a bit boring. Then there is our generation, which is still a mix. Some people are doing work that is more or less relevant, but it’s also more or less aesthetic. It can engage on a much more conceptual or ethical level. And then I think there is a new generation, a completely different one. And it’s also a striking one because I think while we were able to compromise, this new growing generation cannot at all; they are very radical. Of course, you need to pass through a moment of radicalism. I mean, we were also much more radical at the beginning than we are now probably. But still, we were looking to find some common ground, a meeting point with the industry. I think this new generation really doesn’t trust the establishment anymore and that’s very good. On the other hand, it’s also very dangerous because there aren’t many big corporations in design, but as soon as you just jump into fashion and tech then you have billion-euro companies, they are really controlling and moving resources and money. Not talking to them can be a missed opportunity because in the end, they are actually the ones that can make the change. The new generation seems a bit uncompromising at the moment, even if this is, of course, a generalisation, but…

Furniture, Cambio exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, 2020

Where do you teach?

So, it is an academy. We are the heads of a department. It’s a two-year master’s program called GEO-Design, which examines the infrastructure upon the way design is performing, so we are looking deeply into the ecological concerns of production in today’s age. And at the moment, it’s also a non-media-based department, we are not linked to a specific medium; we work with videos and performance as well. That’s also something we quite want to keep, especially nowadays. We want to explore as much as possible in different languages, and I think that we will go more and more through the product, hopefully. Above all, we are looking holistically at what it means to produce today and the geography of production.

Sketch by Formafantasma

We tend to agree. Maybe for your generation, it was really tough because there were not as many radical opportunities… Now there are more independent editors, for example in Paris we have lots of emerging editors with small, limited collections, a more artistic approach, design galleries, self-edited series, and it feels similar in Europe or the United States. The radical approach also cleverly embraces this movement to be able to reject bigger industries. We feel it was potentially, and maybe paradoxically, tougher to graduate in 2009, having sustainability in mind.

Exactly. But also because it was a completely different moment in time, there were still these ideas of design “stars”, you know “authors”… Don’t get me wrong we are also authors, we are not a collective of twenty designers. We are still two people, so we are still in that system. We see with our students that they are all working as collectives and it’s also very interesting and relevant. But it was difficult. Of course it was.

Teaching, is that also a way for you to work on the transmission of your ideas on sustainability or explore that area more?

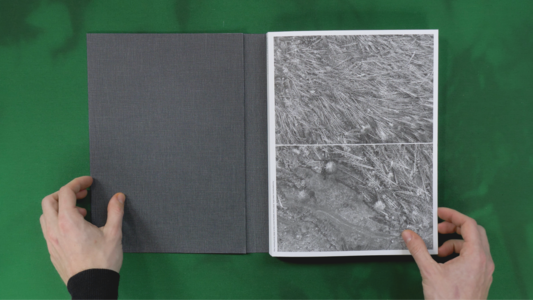

Of course. What you do when teaching is to engage with the new generation, which can also amplify your thinking. The educational part is really important in our practice, you can see it from the work we do on a curatorial level. Some of the works are very scholastic in a good way, didactic. If you think about Cambio, the project we did at the Serpentine Gallery about the timber industry, it’s an educational project, especially the catalogue we did for the project, which included many interviews and other texts. For us, it’s all about that, the educational approach.

Catalogue, Cambio exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, 2020

Catalogue, Cambio exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, 2020

Among the younger people you’re teaching, you mentioned some of the evolutions, them being radical, are there any other evolutions you see?

Well, there is for sure an interesting material exploration. It’s very healthy because in order to understand processes, you need to understand materiality. And if I think about how we were designing back then, in 2005 when we were studying in Italy, you were designing, you know, equipment. Designing, for example, a coffee machine, not really thinking about everything that was surrounding the production of the object. Nowadays, all the students are really interested in material exploration, understanding where the materials come from, engaging with the community that produces that material, understanding the location and the context where the material grows, if it grows. And understanding the line of production and consumption of that object, and ultimately its life after consumption, so there is a better understanding of the ecosystem surrounding the objects.

You also mentioned some of the students having a more collective approach. It’s really funny because, to us, Formafantasma is an author in design, but you chose a name other than your own…

Exactly.

When you were students and you’ve still kept it throughout the years. Can you tell us more about this?

Actually, when we founded Formafantasma we were also thinking that the name was a bit hilarious, and at certain moments we also thought we should maybe change it, it wasn’t serious enough maybe. Now we are okay with it, we don’t even think about it anymore as a word. It’s okay. It is what it is. But it was interesting because it was referring to the fact that our work back then—and to this day—is not really related to form. You know, fantasma means “ghost,” so it’s a form that changes. We decided to keep it and not put our names on it. We still put our faces. Sometimes we think we should remove them. And, in a way, we’ve started to do that. If you go to our website, you don’t find our portraits anymore. But then there is also the narrative around design and authors. It’s also okay, we are the heads of the studio, and we speak for the studio. But it’s not just me and Simone: it’s a group of people that work with us. We are a voice for the group. There is a will for inclusion, to name the people that contribute. If you check our website, all the people that work on a project are credited. It’s a very simple thing, but 90% of the studios don’t do that.

That’s great thank thanks for all of this. If we just wrap up with some more trivial questions, there’s one question that we really like, which is if you had to do another job at another time in history, what would you do and when?

Well, I think it would not be something related to making of any kind. I really love history a lot. And I probably would have become a historian. Art historian.

And any period?

This century. I would never live in a century other than the 20th or 21st century, too dangerous before.

Are there books that have helped you in your life and your design career that you would recommend?

A lot of books. Well, Staying with the Trouble by Donna Haraway is one of the most relevant books of our time. But The Mushroom at the End of the World by Anna Tsing is another book that we love. An additional one that I think has been very instrumental, especially for our previous work, is Should Trees Have Standing? by Christopher D. Stone. It put the rights of other beings at the centre.

Furniture, Cambio exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, 2020

And the last two questions. What’s your advice for creative talents starting a career nowadays?

Say no. A lot. Especially in the beginning. In the beginning, you don’t have resources and, most of the time, companies exploit you. So why should you compromise? There will be a time for compromise. As I said before, we were much more radical at the beginning than we are now. The beginning is the moment in which you need to pursue your ideal scenario as much as possible with the means that you have. We come from very simple families, and we have moved, me from Sicily, which was a very poor region of Italy. It still is, but it was even poorer before. We obtained what we wanted without really having a lot of money in our hands. So, it’s not about money, especially at the beginning, because you don’t have money regardless, so don’t compromise.

And any more advice for people who specifically want to develop a design practice?

Good luck! [laughing] It’s difficult. It’s very difficult. Also, they need to think about what design means today. We really need to work with a much more expansive understanding of the discipline that is not only about designing the product. There are a few companies and thousands of designers, so there’s not space for everybody. You need to find your own way of working.

Mondo Reale, Fondation Cartier 2022