Hi Zak, could you introduce yourself?

Sure. I’m the founder and creative director of Zak Group, a design office based in London.

Zak Kyes, Photo: Gabby Laurent

You have got many activities; how would you present them or summarise them?

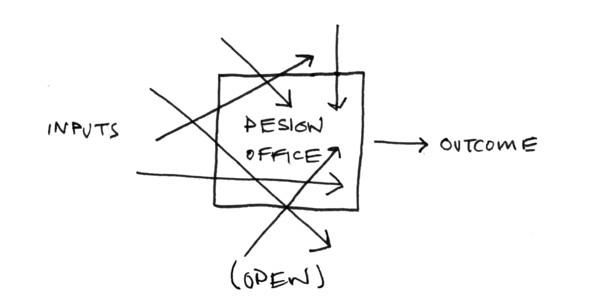

Zak Group is a design office. Not a studio or an agency, but an office: a place where work can happen and things can be created. Our work focuses on identity and creative direction for people, institutions and brands guiding the trajectory of contemporary culture. We’re interested in the freedom to do multiple things, so we try to keep this definition open.

What’s your current state of mind?

The last few years have been difficult, and it continues to be when you read the news. It’s been a challenge to run a creative business and to make work that’s relevant and engages with the present. This has caused us to focus on what matters most to us. It led to a few specific projects like the Future Forward Scholarship at Central Saint Martins which we launched last year. This gives a student from an underrepresented background a three-year scholarship equivalent to tuition fees, plus mentorship and paid internship opportunities from the association of studios funding the scholarship. This year the scholarship was made possible by Pentagram, Some Days and Zak Group.

ICONS, Virgil Abloh (Taschen, 2021)

ICONS, Virgil Abloh (Taschen, 2021)

What got you into graphic design in the first place?

I’ve told the story before, so sorry to repeat myself. I grew up in a small town in Southern California to an American father and a Swiss mother. We were family friends with European émigrés, including an older German couple that escaped before the war. As a teenager I was obsessed with their library and when I would visit they would show me their art and design books. They introduced me to the work of their friend, Herbert. Herbert Bayer didn’t mean anything to me, but I became fascinated with his work and the Bauhaus where he taught. His practice combined art direction, advertising, sculpture, and architecture in a strange new hybrid. As a high school student, Bayer became a formative model of what an artist or designer can be. In a roundabout way, it led me to graphic design: first I studied art history in upstate NY and later design at CalArts — a hippy Bauhaus that combined dance, theatre, visual arts, and graphic design under one roof.

You were quite young when you founded Zak Group. Had you already had experience by the end of your studies?

Zero experience. For better or worse. When you’re young and naive, you think you can do anything because you don’t know the rules. I thought I could just set out alone immediately and start a studio. So that’s what I did: I graduated from CalArts and moved to London in 2005, and I soon after started working with the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA). At twenty-three, I became the art director of the AA and started my own office.

Zak Group office, Photo: Gabby Laurent

Zak Group office, Photo: Gabby Laurent

Zak Group office, Photo: Gabby Laurent

What was your intuition? Did you think of it in terms of an independent studio or a global agency?

I saw graphic design as a way of giving shape to culture and actively being a part of it, rather than just packaging it. That was, and still is, my conviction. My intuition was to follow this simple idea and see how far it could be taken. I found different references along the way that helped me to believe in this potential.

What were those references?

Many of the references came from my work art directing the Architectural Association. The AA was my MA in a way, because it was like going back to school. ‘Paper architecture’ became an important reference. I was exposed to architects — some new, and others that I had studied — like Superstudio, Archigram, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, who were all working on immaterial and hypothetical projects that took the form of books rather than buildings. The ‘little magazines’ from this period showed me how graphic design could play an essential role in cultural discourse.

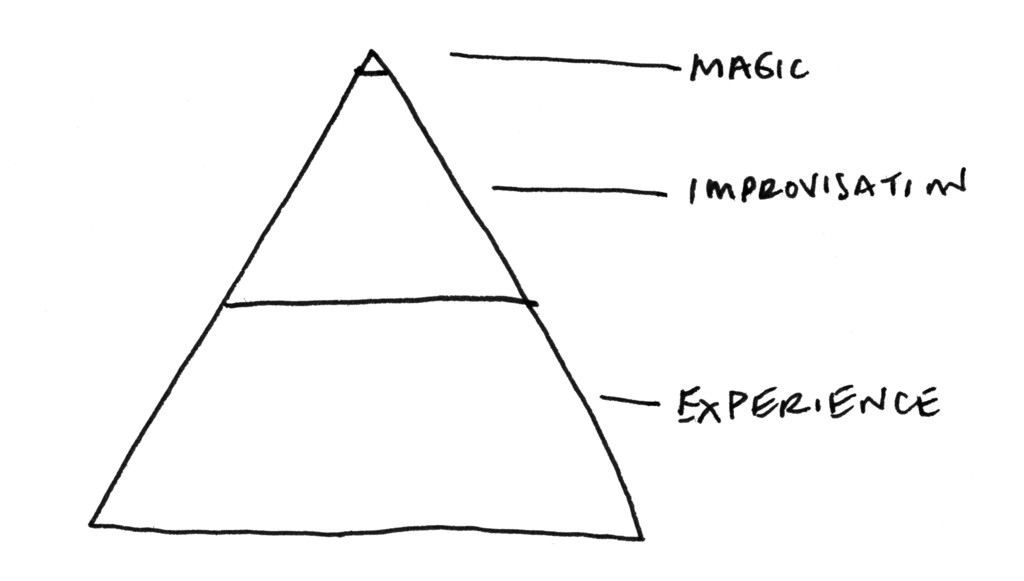

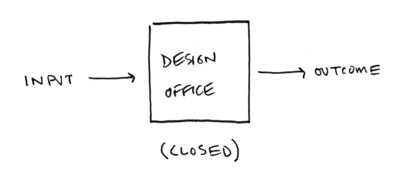

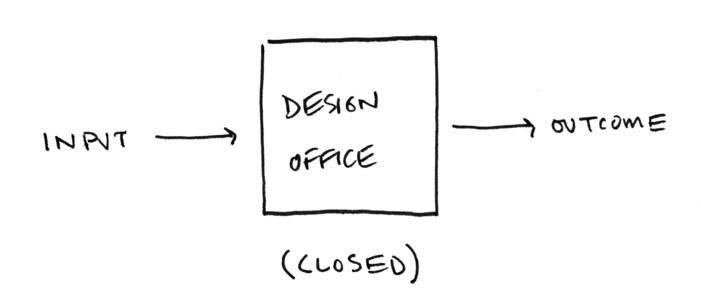

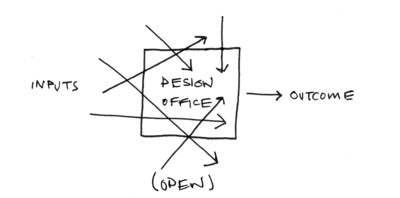

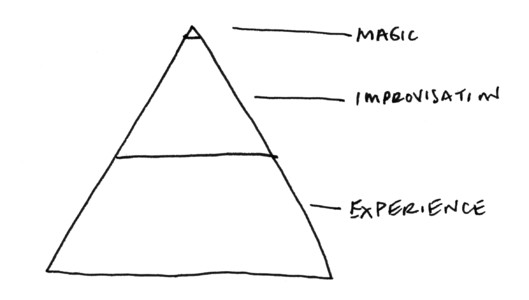

sketch by Zak Kyes

sketch by Zak Kyes

Are you saying that architecture influenced the way you approach design?

Architecture as a conceptual toolbox, yes, and paper architecture is just one example. I was searching for tricks and tools that I could borrow and apply to a graphic design practice. This is what lead to starting the publishing imprint Bedford Press (2008-16) or exhibitions that I curated like Forms of Inquiry (2007-09).

Are you still interested in architecture?

Yes, this is still a very important discourse. Architecture, like graphic design, is very porous. Anything can be graphic design. Many of the architects I know or admire essentially produce knowledge: exhibitions, books, and ideas.

We have also interviewed many architects, and it is interesting to see their self-professed “architect syndrome,” wanting to design everything: from the building to the furniture to the visual identity. Would you say that you also have a global vision of design, an urge to expand your scope?

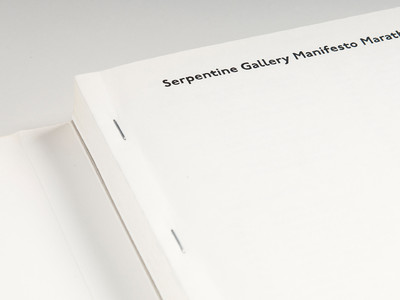

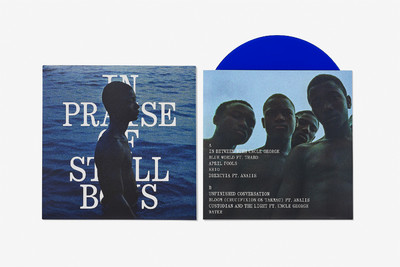

The Gesamtkunstwerk syndrome? It came to us gradually. You start by designing a book for an institution, then you think about the exhibition it accompanies, then the visual identity of the institution that hosts it. As you go further upstream, the opportunity to have a greater influence increases. Your vision widens. It actually becomes a question about creative direction. At the same time we organically grew alongside our collaborators. Like Hans Ulrich Obrist, who was actually the first curator I ever met and who has been the best, and most generous supporter of our work. I had recently moved to London and a friend was starting a club, the Brutally Early Club, with Hans Ulrich and asked if I wanted to join. We would meet at the Vingt-Quatre cafe on Fulham Road at 6:30am because, as Hans Ulrich explained, nobody has ‘prior comittments’ at 6:30 in the morning. Our first project together was the Serpentine Gallery Manifesto Marathon in 2008 which led to many more. But I’ve had similar experiences with artists, like the Sierra Leonean poet and film-maker Julian Knxx, where we started with one project, his exhibition In Praise of Still Boys and it just snowballs, simply because you believe in each other…

Serpentine Gallery Manifesto Marathon, ed. Hans Ulrich Obrist (Koenig Books, 2009)

In Praise of Still Boys, Julian Knxx (Vinyl Factory, 2021)

In Praise of Still Boys, Julian Knxx (Vinyl Factory, 2021)

You started out working with institutions, and now you are working with global brands. Was this intentional? Did it happen because your notoriety was growing?

Our focus has always been to work in culture. Around 2015, we had the epiphany — that sounds like a grand statement but it’s true — that culture is not limited to visual arts. Brands, events, music and fashion, play an integral, and sometimes greater role, in shaping the culture. We also realised that we could facilitate opportunities for brands to support culture, like we did earlier this year with the Woolmark Prize where we initiated a collaboration with the estate of Isamu Noguchi and the artist FKA Twigs. Our focus has expanded from Culture with a capital “C” to “culture” with a lowercase “c.” It then became a deliberate choice to expand who and how we work, even if what we do is the same.

Still from Playscape (International Woolmark Prize, 2022)

International Woolmark Prize Showroom, Photo: Sophie Stafford, Courtesy Studio Boum, Noguchi artwork © INFGM / ARS – DACS

International Woolmark Prize Showroom, Photo: Brotherton-Lock, Noguchi artwork © INFGM / ARS – DACS

It is sometimes difficult for studios anchored in cultural projects to expand their activities to brands. It is interesting to hear that you consciously wanted to do that. How did you manage that? Did you have a specific strategy? Did you meet specific people?

It happened a little by chance. There was a moment when Julien Dossena, the artistic director of Paco Rabanne, approached us because he was taking over the brand which had been founded by an architect-turned-fashion designer. The founder, Paco Rabanne, had a very avant-garde approach of building clothes out of metal. Julien was interested in looking beyond the usual suspects and found in us an understanding of architecture and art that could provide a different perspective on his world of fashion. It was an important bridge. In music, it was the same case with Frank Ocean. At the same time, the practices of artists we were working with like Anne Imhof started overlapping with music, fashion and architecture. And then it became a matter of finding the people working within brands with whom we could have relevant, meaningful conversations.

sketch by Zak Kyes

Are you handling this kind of strategic thinking? Do you have help?

It’s more intuition and trial-and-error, than a strategy. We work with the agency Huxley, who represent us and some of our clients. It’s something that we discuss as a team, with Belle Place, our senior design operations manager, and Asel Tambay, our art director.

What advice would you give to younger generations wishing to launch their own studio?

It might sound counterintuitive, but my advice would be to avoid perfectionism. You should ask yourself two questions. Is it done enough? And, is it good enough? If the answers are yes you should move on. Perfectionism ultimately limits and inhibits creativity.

How do you maintain your independence?

Independence can mean a lot of different things. I put a high value on independence, but even so I’m not sure you can ever be totally independent.

Natures Mortes: Anne Imhof (Palais de Tokyo, 2021)

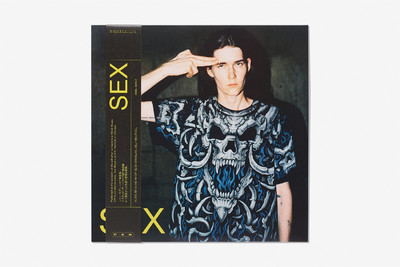

SEX: Anne Imhof, Eliza Douglas, Billy Bultheel (PAN, 2021)

How many people are working currently at Zak Group?

There are seven core members. Zak Group is currently Asel Tambay, Belle Place, Chi-Long Trieu, Florence Meunier, Melissa Ramos, Marta Úrbez, and myself. We also work with lots of regular collaborators like our agency Huxley, Dyvik Kahlen Architects, the writer Charlie Robin Jones and lots of type designers, illustrators, programmers and photographers.

You are self-taught. How do you approach management?

You can’t run a successful office just by being a great designer. I came to realise that creativity versus management is a false dichotomy. I’ve seen inside the studios of established artists and the idea that art is some kind of free zone is a big illusion. Many artists are actually really, really great managers and know how to surround themselves with great people. Yet art school is probably the worst place to learn any of this. Why is it a taboo? I try to create an environment where there is a diversity of ideas and backgrounds. It’s not my job to be the best designer, but to make sure that the team produces the best possible work. That means making decisions, giving directions and on a really fundamental level, caring.

Zak Group

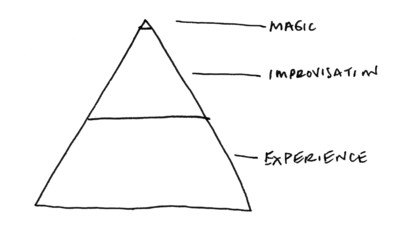

Do you have an ideal size for a design studio? Could Zak Group have 50 members?

It’s hard to find 50 good people, let’s be honest! We could be larger than we are today, but it comes down to the question of how do you scale creativity? Production is easy to scale, but creativity is more fragile.

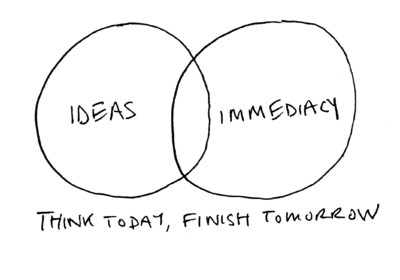

sketch by Zak Kyes

That’s when you would lose the spirit and the style? What’s the culture like for Zak Group?

That’s when you could become imbalanced. Implied in the name Zak Group is the idea of a group of people working together, like the Independent Group or the Bloomsbury Group. I like to think of Zak Group as a piece of creative infrastructure: able to scale and join forces with our collaborators and clients to amplify their ideas and ours. Our work is the product of the group, not of the individuals that compose it.

Nike Art Direction, Photo: Sergiy Barchuk

Nike Art Direction, Photo: Sergiy Barchuk

Nike Art Direction, Photo: Sergiy Barchuk

Nike Art Direction, Photo: Sergiy Barchuk

You mention some elements not being scalable, the creative part of a project. What’s a typical working week like for you? What time can you still spend on the ideas when you have to manage people, the business side, the creative side?

Last year, we created a new role to lead our design and business operations. That has freed up a lot of my time to work with designers on proposals. Most of my time is spent on developing ideas with the team, writing proposals, working with clients to develop briefs and generally keeping a hand on the wheel.

How do you handle the business development side? Is it just incoming calls, organic development? Or do you have times when you sit down and evaluate the need for a strategy? How do you learn to say no?

The best business development is to do great work and make sure the right people see it. If I’m genuinely interested in what someone is doing, I’ve always believed in making the effort to tell them. We’re very lucky to be at a stage where we can say no. Because ultimately our time is finite and you need to decide what you want to spend your time on and with whom.

You have cultural institutional projects. Do you accept consultations and pitches?

No, we don’t pitch design ideas. Once in a while we might “diagnose” what we think the problems and opportunities are. We’ve been lucky to be able to work with public institutions, without going through the pitch process. I don’t think pitches are conducive to doing the best work.

We totally agree, but could you expand on that?

A pitch is something that a group of people will need to agree upon. Nobody takes a risk. Good ideas require risk, also of the client, who should put their reputation on the line too. That would never happen with a pitch. At best it’s a shot in the dark, at worst it encourages mediocrity.

We’re also curious in terms of communication about the Culture Is Not Cancelled campaign. Can you tell us what drove you to speak out?

Budgets for cultural projects are always the first budgets to be cancelled in a crisis. When the first lockdown came into effect, it became clear that cultural projects were going to be cancelled. That affected us directly. Culture is a fundamental part of society, it’s what makes us human and defines us. Culture should be the last thing to be cancelled. We felt it was important to say something. It wasn’t intended as a campaign, but it became one as the message resonated and was embraced by others. First with art and culture magazines and then it ripped out further as institutions used it as a way to highlight programmes that responded to the pandemic. We produced t-shirts and stickers, with sales benefitting our Chisenhale Gallery, one of our favourite art spaces in London.

Do you remember wondering about the action of speaking out on a personal level?

No, not at all. We just did it.

How would you describe the current creative market now, at the beginning of 2022? Are there things you really like? Others you are sceptical about?

The market is challenging because the more successful something becomes, the less people want it to change. We are interested in finding ways to create new things, fresh ideas. And to do that you have to go outside of the mainstream, the dominant channels. And of course, if it works, it eventually becomes the mainstream.

8th Berlin Biennale (KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2014)

8th Berlin Biennale (KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2014)

8th Berlin Biennale (KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2014)

What do you think about fashion’s craze for the metaverse?

When I think about game-changing technologies, they start out as being utopian and useless and only later is a use ascribed to them. But when you see new technology that arrives already monetized — like fashion in the metaverse — well, it’s not interesting. I was part of the first generation that grew up when the internet was invented. It was a paradigm shift. On the other hand, I think the decentralisation that the blockchain allows will have a similarly profound impact.

You mentioned the importance of being independent. Have you had any offers or potential investors? What are your future plans for Zak Group?

We were approached once. But so far, the compromise of independence would outweigh the benefits. In terms of future development, I’m interested in expanding our scope. We started out as a team of graphic designers, then as the projects evolved to require other specialisms, we became art directors and now some of the projects require creative direction. I see a lot of potential for creative direction as a way to apply our design thinking.

In Paris, we are witnessing many opportunities arising for smaller-sized studios outside of the usual classic fashion and luxury brands. Have you got a similar feeling?

Yes, brands want a different perspective because, ultimately, they want to become — or stay relevant. They want to invest themselves in culture. And this is something that the classic agency model can’t do. The documentary short Sub Eleven Seconds about Sha’Carri Richardson by the filmmaker Bafic is a great example. It’s a stunning artistic work, but it’s also great for Nike. In architecture it’s the amazing spaces designed by Niklas Bildstein Zaar for Balenciaga. In fashion it’s Benji B.’s musical direction of Louis Vuitton and the amazing shows that have included Tyler the Creator and Kendrick Lamar.

Nike School: Chicago

Nike School: Chicago

Let’s finish with more trivial questions: if you were to do another job in another period, what would that be?

I recently read Diaghilev: A Life, a biography of Serge Diaghilev, founder of Ballets Russes. He was an impresario, a catalyst, a junction maker. That would have been fascinating.

Any other books you would recommend in terms of creative or strategic developments?

In terms of style, I love Joan Didion’s writing because you can recognize her voice from a single sentence. As a designer, the ultimate goal of design is to give your voice to the subject matter and Didion does that so economically and unmistakably in her writing.

On the topic of strategy and behaviour, Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman, describes cognitive biases and explains how our gut reactions often override our rational decisions. One example that’s relevant to design is the “framing effect”: how people can respond differently to the same thing depending on how it’s presented.

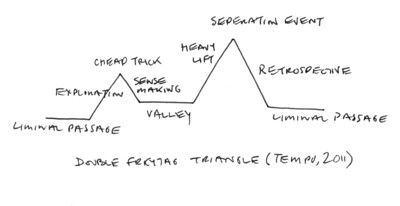

And lastly, I can recommend Venkatesh Rao’s oddball book Tempo and blog Ribbonfarm. Essentially, it’s a book about storytelling and decision-making. You should google “Double Freytag Triangle.”

sketch by Zak Kyes

Any last advice you would give to young creators?

It’s good to have doubt. Doubt is essential to creativity. It’s what keeps you up at night, but also what drives you to question and improve your ideas. If you’re absolutely certain of something, it means you haven’t thought deeply enough. Doubt isn’t the antithesis of confidence.