Could you please introduce yourself?

My name is Brent David Freaney. I’m an Art Director and I live in New York.

Brent David Freaney, Founder of Special Offer

How do you present your current activities?

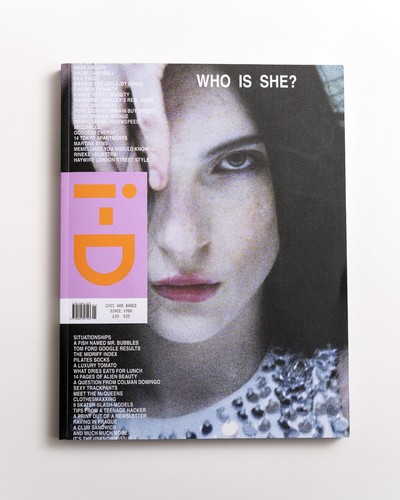

I run and manage a studio called Special Offer. Recently I’ve also become the Art Director of i-D magazine.

Special Offer’s offices

What’s your current state of mind in April 2025?

I’m feeling good. Last year was really, really wild, and now I’m feeling excited for what this year has in store. But I also want to make sure I’m approaching it in a sustainable way—something that keeps me grounded and helps me avoid burnout. You know what I mean ? I just want to go through my days working hard, but also having a real life outside of work. Because I really believe that the more time you spend making sure you’re not constantly working, the better your work actually becomes. So I’m trying to let each part—life and work—fuel the other.

You worry there might be too much going on, how do you organize this?

When I first started the studio in 2014, it was really just me and maybe one or two other people for the first three or four years. Since then, we’ve grown, and now we are a team of eight. Around 2020, right during the pandemic, we really started to grow and hit our stride, and I feel like I’ve just been going nonstop since then. Pretty much all of my work over the last few years has been focused on building the studio and growing the practice. Now, I am at a place where I’m interested in letting that momentum continue on its own a bit, and shifting my focus to other aspects of life. Like… should I get a hobby, for example?

Are you considering any at the moment?

No.

Special Offer’s offices

The shift from still being hands-on with design to stepping into more of a creative direction role is such an interesting transition.

I’ve always been a designer. I am like a lot of people in art direction or creative direction roles who don’t necessarily come specifically from a graphic design background. It’s been both interesting and challenging—but also really rewarding—to let go of the need to physically touch everything myself. There has been something really nice about learning to step back and trust the process and the team.

Special Offer’s offices

If we go back to before your career started, what got you into graphic design or art direction?

I grew up in a small town outside of New Orleans, in Mississippi. When I was in high school—around 1999 to 2003—there really weren’t a lot of people in my community or at school who shared the same interests as me. So I used the Internet as a way to create a community for myself. This was pre-social media—before MySpace, before Friendster. I was specifically on LiveJournal, and that’s where I started finding my space. I’d come across these personal websites people were making for themselves—often fan websites dedicated to a band, an actor, or some niche interest. They were usually in that early Geocities style, kind of raw and DIY. But they felt like people carving out their own little corner of the Internet, branding it with their own personality. This was before platforms like Instagram or Tumblr existed—places where you could customize an entire page to reflect who you were. Back then, you just designed something in raw HTML and put it online. That’s how I got into it. Even though I had taken a graphic design class in high school, I was more interested in the interactive and community-building aspects of design. I was really drawn to what the Internet made possible. At the same time, I was getting deep into music and subcultures, and one kind of fueled the other. I’d spend hours listening to music and building these small websites—just getting lost in the artwork and aesthetics, especially around musicians and artists. I’ve pretty much always known I wanted to be a designer, from around age 13 or 14. Even before that, I was really obsessed with my handwriting—to a kind of unhealthy degree at times. But I was extremely focused on how perfect I could make it. I didn’t realize it then, but in hindsight, that was my early interest in typography. Back then, every note I took in school, every letter I wrote to friends—I cared way more about how it looked than what it said. That was probably my first real sign that I was headed in this direction.

Did you study design after high school?

I studied design after high school, but I ended up dropping out of college—it wasn’t the right fit for me. As I mentioned, I grew up in a really small town in Mississippi, and I was eager to get out. Through LiveJournal and the Internet, I had started forming these early parasocial friendships with people who mostly lived in California. We’d never met in person, but we were all fans of the same bands and shared similar interests. By the time I was in 12th grade and starting to look at colleges, I already knew I wanted to move to California. I basically found a college that was as close as possible to where I wanted to live, and I used that as a way to make the move. Once I got there, though, I realized the school wasn’t really a match. I dropped out. I think even back then—this would’ve been around 2003—I had a sense that something was shifting. The Internet was cracking things open, and creative fields like graphic design were becoming things you didn’t necessarily need a traditional education for. The pace of the Internet was moving so fast that schools and curricula just hadn’t caught up, especially when it came to digital and web design, which is what I was really drawn to. I figured out I could use the Internet itself to learn what I needed, instead of following a more traditional path. So I made that decision and didn’t look back.

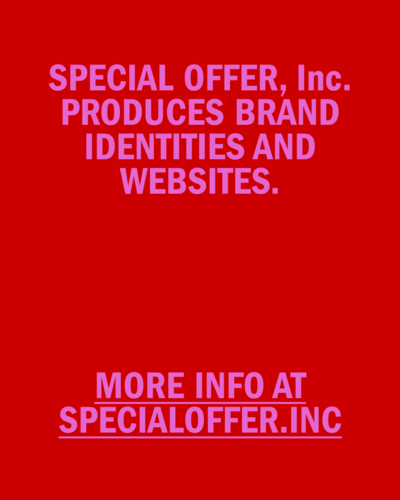

Design by Special Offer for Miley Cyrus Endless Summer Vacation

How long before you founded Special Offer in 2014?

2014 was really when I officially pulled the trigger: I decided to name this thing “Special Offer” and treat it like a proper studio. Before that, I had already been working professionally in a freelance capacity—probably since around 2007 or 2008. In the spirit of what I mentioned earlier—community building, subculture—I was always more interested in being part of a creative community than anything else. I fully immersed myself in the music scene in Los Angeles. I played music for a while, went to all my friends’ shows, and eventually became the go-to person in that world whenever someone needed something designed. It was very informal—I wasn’t thinking of it as a career yet. It was more like, “Oh, you need merch? Brent can do that.” Or, “Need a website? Go to Brent.” I was just helping friends out, contributing to what they were already building. And in the process, I was figuring out how to build something of my own and make a bit of money along the way. That went on for about five or six years before I decided to formalize things and start a studio in 2014 because I wanted to create something a bit more official. I had started out specifically in web design and development—I taught myself how to program just enough to get things online. And I realized early on that it was easier to get jobs if I had an entity name that wasn’t just my own. It added a layer of ambiguity. If I approached a company or a client and pitched a website, they wouldn’t necessarily know how big or small the operation was. If it was just me, under my own name, it might come off like, “Who’s this kid trying to help out?” But with “Special Offer,” even when it was just me doing everything—design, development, working day and night—it gave the impression of something bigger. It was like this useful little cloak that made it easier to get in the door.

Which instruments were you playing?

I’ve played guitar pretty much my whole life. It’s never really been a super formal thing, just this hobby I’ve had in the background. I wouldn’t say I focus on any particular style. It’s more about learning songs I like and playing rhythm guitar as a sort of backing track for myself while I’m at home singing, or just messing around. It’s always been that low-key, personal kind of thing for me.

What was your intuition when you founded Special Offer ?

I’ve always had kind of an entrepreneurial spirit. I’ve always been trying to figure out how to make things work—how to maybe make a little money or leave a mark in some way. When I moved to Los Angeles from Mississippi, I really had nothing. I spent a few years working some really awful jobs—at one point I was a carpet cleaner. I also worked retail, restaurants, all kinds of jobs that just felt like such a bad fit. Once I was able to carve out even the smallest living doing the kind of work I actually wanted to do, I poured everything into growing that. There was definitely a fear of going backwards—of having to go back to cleaning carpets or taking on jobs that felt so misaligned with who I was. One thing I’ve always learned is what I would call the “performance” of design: the performance of conversation, of being in a room with someone and talking through an idea. If I could get someone on the phone or in front of me, I could usually do the song and dance that would land us the job. Whether or not I actually knew how to pull it off at that exact moment was another story—but I knew I could figure it out. I’ve always been a good salesperson in that way. At some point, the number of projects started growing beyond what I could handle alone. From 2014 to 2019, Special Offer was really just me and one other person—Gabby Datau, a designer I’d been friends with for a long time. But by 2019–2020, we started to feel a shift. There was more interest in the studio, more opportunities coming in. We had already done a lot of websites—especially e-commerce sites, which were starting to boom around then. And we’d worked on identity projects for fashion brands and musicians who, at the time, were still emerging but soon started getting real attention. For example, the band Haim was always around—we were friends in the same community. When they started getting more visibility, the work we had done for them started getting seen more, even though it had been done before their rise. The same thing happened with other projects—we had built a website for Martine Rose, and as her profile grew, that work got more attention as well. In 2020, especially after we launched the Martine Rose site—which was such a fun and inspiring project, maybe the first one I was truly thrilled about—we started seeing a real wave of interest. Inquiries picked up, the projects got bigger, and we realized we could start hiring more people. That’s when things really started to grow.

Work by Special Offer for Martine Rose

What were your first creative references and inspirations ?

Something I’ve always been obsessed with is the New York subway system. I didn’t officially move to New York until I was about 34, so for a long time, New York just existed in this kind of fantasy space in my mind. When you don’t live somewhere but visit maybe once a year, it kind of lives in this utopian version of itself in your head. The work Massimo Vignelli did on the subway system—creating this entire visual world—was always something that stuck with me. From a graphic design perspective, it really resonated with me from the moment I discovered it. It felt so complete and intentional, and that kind of thinking has always been really inspiring to me. At the same time, going back to music and the stuff I was into in high school, I was always really drawn to what musicians, bands, and artists were doing visually. A lot of the time, that design work is really collaborative, the artist is heavily involved in shaping how the final thing looks and feels. That process of collaboration really interested me: what happens when designers team up with other creative people who aren’t necessarily designers to bring their ideas to life? That dynamic—the push and pull between vision and execution—has always been something I’ve loved exploring.

Are there some covers that were specifically inspirational to you?

Honestly, one of the first things that really stuck with me was this CD I got in middle school called Schoolhouse Rock Rocks. It was this compilation where a bunch of ‘90s bands—like Smashing Pumpkins, Lemonheads—covered songs from Schoolhouse Rock. I remember when I bought the CD, it came in this opaque yellow jewel case—you couldn’t see through it at all. It had this super colorful sticker on top with a bunch of bold typography. And for some reason, it just really hit me. I remember thinking, like “Who designed this? Why this color? Who chose this?” That was one of the first times I can remember really noticing design like that. Something else that was hugely inspirational to me was the TV show The Real World. I was obsessed. It was probably the first reality show, right? On MTV—seven strangers living in a house together, all their interactions filmed 24/7. For me, growing up in Mississippi, it felt like they were having the kinds of conversations I wanted to be having. There was just something deeper happening there, something under the surface that really captivated me. When they started filming The Real World: New Orleans, I lost it. Since I lived close by, my mom would literally drive me after school to the house where they were filming, and I’d just hang out outside, hoping to catch a glimpse. Eventually, I got kind of loosely connected with one of the cast members—like, not friends, I was 14 and they were in their 20s—but she started giving me music to listen to, movies to check out, all these cultural references I never would have found otherwise. All the motion graphics and visual identities MTV was doing in the late ‘90s and early 2000s was huge for me. It was this blend of early digital aesthetics but still very analog, and I was totally drawn to that. If you trace back this whole visual language, it really connects to the kind of Massimo Vignelli-style design work—the clean systems, the intentionality. All those influences were part of the same family tree, and that’s what shaped me early on. I was never really into the David Carson, super-grunge style of design. It always felt too heavy, too chaotic for me. I was more interested in simplicity—design that used color as a focal point, that felt bold without being overloaded. That yellow CD case, for example—it’s just color and type, but it felt electric and I’ve always chased that feeling.

How do you maintain your creativity?

For me, it really all comes down to partnership. Whether it’s the person I’m working with, the internal or external team, or the client, what matters most is trust. If there’s this unfiltered, mutual trust, then that’s the kind of project I’ll throw everything I have into. On the other hand, if that trust isn’t there, I’ll still do the work, but I’ll know not to invest too much of my creative energy into it. Not everything is the right fit, and I’ve learned to recognize that. I’m always trying to operate from a flow state when I’m designing—and that can really only happen when I feel good about the project and the people involved feel good too. I want to spend my time and energy on projects I care about personally, the ones that actually make me feel something. And that’s been a hard lesson for us to learn as a studio, because as you’re growing, and trying to sustain a business, you sometimes have to take on projects you are not super excited about. You’ve got to keep the lights on. So the trick becomes learning to identify which projects you’re going to be emotionally invested in, and which ones you’re going to simply execute to the best of your ability. I always try to have just one project on my plate at a time that I’m fully committed to—the one that I’m the most devout to, the one that consumes the most space in my brain. Because I know if I give that level of energy to every single project, it’ll burn me out. Projects also have a rhythm to them—an ebb and flow. Sometimes something might not feel that meaningful at first, but it can evolve into something really powerful. And vice versa. So I try to find that moment in every project where it does become meaningful and then when the timing is right, I’ll pull back and redirect that energy elsewhere, letting that first project continue to move forward in its own momentum.

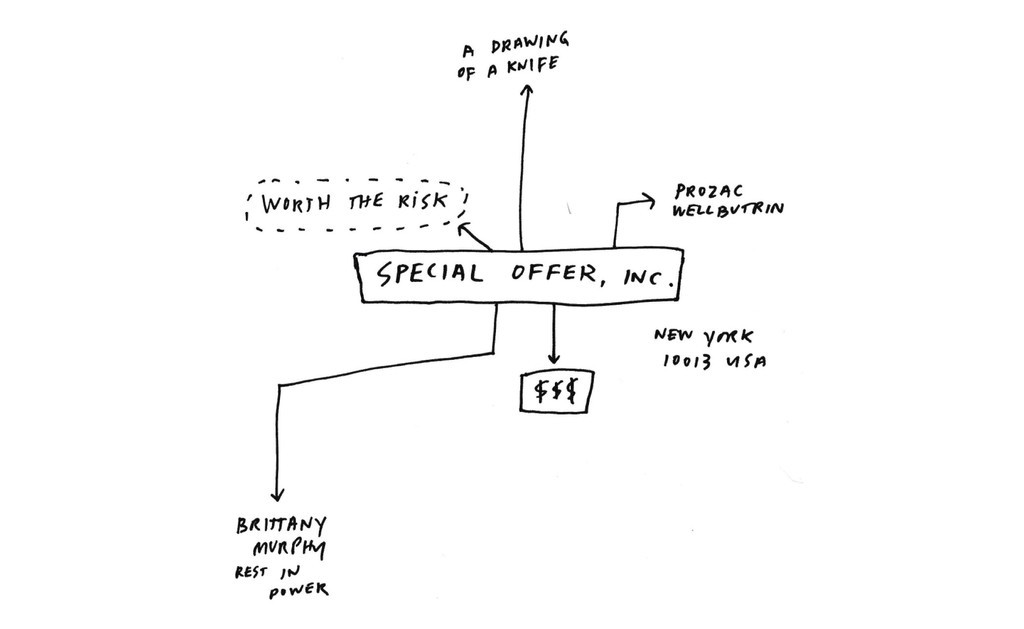

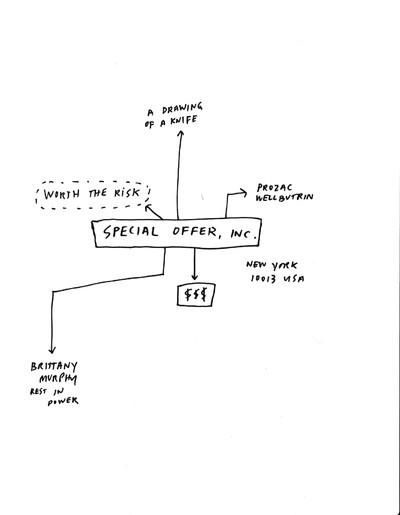

Sketch by Special Offer

It’s interesting because those are also personal and work ethics, but also very strategic decisions. Do you also have some strategic references?

I don’t have any specific strategic references I think about consciously, but I do feel like I run my business in a very strategic way. I’ve always been pretty good at that. I really believe that manifestation is a powerful tool. If you believe you’re going to do something, or that you want to do something, and you stay open to it, it will find its way to you. I think it’s about playing the cards you have in front of you to get to the next thing—while staying humble and genuinely excited about what you’re working on in the present moment. From an entrepreneurial standpoint, I’m constantly thinking, “Okay, what’s the next step?” And sometimes that “next thing” might be something bigger, but honestly, a lot of the time it’s just something I’m more interested in at that moment. Lately, for example, I’ve been really curious about filmmaking. I haven’t made a film yet but with each project, I do find myself asking, “Where are the moments here that could move me closer to that?” It’s not a conscious strategy per se, but more of a subconscious pull in that direction. And I think that’s part of what’s led Special Offer to doing more motion graphics, more film titles, opening credits, and so on. It’s not a coincidence that my interest in film has slowly nudged us into that space. And that will probably evolve again into something else later on—but I think that’s how I tend to operate. Always thinking a little ahead, even if it’s not entirely intentional. On a more practical level, I think one of the most important parts of our strategy as a studio has been really refining how we communicate. Understanding how we work with clients—not just creatively, but operationally. Thinking about how we function as a creative team and as a production team. Making sure we’re not just coming up with good ideas, but actually executing them in a way that yields the best results. That includes things like: “Who are we presenting to? How are we presenting to them? What’s the format, the tone, the setup?” All of that—those little strategy decisions—can ultimately make or break a project. So even though I might not be consciously pulling from a playbook, I’m always thinking about those layers.

You’re one of the rare studios that seems to have had a real turning point recently, how would you describe it?

There have been so many times over the last few years where I’ve put all my eggs in one basket, thinking the project I was working on would be a turning point. These were large-scale, high-visibility projects—like the work we did with Virgil Abloh, or with Louis Vuitton—that felt like they had to be that moment. I was sure they’d be transformative. But in the end, they weren’t. And I think what I realized is that I was maybe trying to force that moment to happen. I was pushing too hard for the studio to “level up,” to make sure we capitalized on those moments. Like “we did Louis Vuitton—now everyone will want to work with us, right?” But that’s not how it works. I had to let go of that mentality. And ironically, once I did that, things really started to open up. I was recently at dinner with someone who had seen a retrospective show at Yale by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville. One thing they said stuck with me: that she had done so much great work for so many people, and yet most people didn’t even know she had done it. It reminded me that graphic designers rarely get their flowers. We’re there to help make someone else’s vision look and feel amazing, but that credit doesn’t always trickle back to us. For a long time, I wanted that recognition. I wanted those big-name projects—like Nike, or Louis Vuitton—to be the proof point that would unlock every future opportunity. Then last year, we got the opportunity to work with Charli XCX and her Creative Director, Imogene Strauss, on the cover for Brat. It was a very collaborative and creatively open experience. I wasn’t putting pressure on that project to be anything more than what it was. I wasn’t thinking of it as a “career-defining moment.” I was just excited about the collaboration and focused on making something great. And the truth is, the real power of that project came from the music, the marketing team, the entire rollout—not just the design. But we were swept up in that moment, and suddenly the project had this cultural velocity. What’s been so great about Brat is that it has given us this new confidence and made us feel more empowered to present bold, radical ideas—ideas we might have been more hesitant about before. We weren’t always taking those creative liberties because we were still operating from a service mentality. Like, “How can I make this client’s idea the best it can be?” I used to think about design primarily as a service. But now, more and more, we’re thinking about design as a product. As in: “What do we want this to look like?” As a studio of eight people who live and breathe design every day, our perspective has real value. And clients are coming to us not just for execution but because they want our point of view. They’re not just hiring us to be the hands; they’re hiring us for the brain, too. When it comes to the art direction of Brat, Charli had this painfully simple but brilliant idea, and an audience ready to receive it. We were lucky to catch the wave. But I also believe that all the work I had done from 1999 up until that point had built the foundation for the design decisions we made on that project. It might look simple. There’s a minimalism to it. But behind that simplicity is a deeply considered design system—one shaped by years of practice, instinct, and strategy. And bringing those elements together in a way that feels effortless is something I’m really proud of.

Artwork by Special Offer for CHARLI XCX

Artwork by Special Offer for CHARLI XCX

In terms of your own strategic development, what do you consider essential? If you’re getting more incoming requests, and you’ve got this job at i-D, how do you see things evolving?

Over the last couple of years, I’ve been trying to understand my personal identity separate from Special Offer’s one. When Special Offer first started, it was really a way for me to cloak myself as an individual—so I could create this entity that was a bit more ambiguous, where no one really knew how big or small it was. Because of that, the style of Special Offer, the branding, the way it presented itself was all very much a one-to-one reflection of how I would do that for myself. But it’s grown into something different. It’s now its own world, separated from my personal interests. At this point, Special Offer is made up of eight individuals, all with different perspectives, working across different projects. And sometimes the work might not feel or present itself in the way that I, Brent David Freaney, would personally choose to express something. So that’s been a big part of this journey—especially with the i-D job: really understanding the difference between art direction that comes from me, and art direction that comes from Special Offer.

Art Direction by Special Offer for i-D Magazine

Art Direction by Special Offer for i-D Magazine

It’s really interesting because I also noticed that you’ve got a personal Instagram account who has more influence than the Special Offer one.

I don’t know why.

You are the founder but what’s your signature within Special Offer?

Design has always been the way I could grow my practice. It’s always been the product of what I do, though I’ve had a lot of other interests and wanted to create in different worlds. I see Special Offer as a project that I’ve had and will probably always have. As long as Special Offer exists, it will be a part of me, but it’s also a product unto itself. The design work we do at Special Offer is one product, and Special Offer as a whole is another. I’ve put a lot of time and energy into understanding how Special Offer should be branded, how it should feel, how it should present itself, but also how it should run as an agency, as a production company. How should our producers write emails? How does our sales strategy work? What does the process look like when inquiries come in? How do we decide what’s a qualified lead, what projects we want to take on, and which ones we don’t? There’s a whole world behind that. What’s been really nice is stepping back and thinking separately now—revisiting how I, as an individual, want to work. I kind of jumped into creating Special Offer, which was a fast-forwarded way of building a business and creative studio, instead of growing organically as a graphic designer or artist first. Now I’m looking at it from a different angle and thinking about what kind of things—music, art, film, and even family—are next for me. What are the things that will feel fulfilling, especially as I move into my 40s? My 30s were very much about building Special Offer, getting it up and running, and working. But now, I’m looking forward to designing without a client in mind, creating things that come from within rather than working on projects for hire. Something more personal, more fulfilling.

How will you maintain your independence over the years? Or do you wish to maintain it?

I would opt for staying independent, I have a lot of opinions. I think that Special Offer will likely remain independent forever. Of course, I’m open to any conversations that come our way, but I strongly feel about maintaining our independence. We have a core set of values that are really important to how we operate on a day-to-day basis. For one, we have a four-day workweek. We only work Mondays through Thursdays, from 10 am to 6 pm. Everyone here is a full-time employee, not an independent contractor. We have payroll every two weeks, providing job security. We also offer health insurance, medical benefits, 401k, and retirement plans for everyone who works here, which, unfortunately, isn’t very common in the U.S. When we started growing the business, it was crucial to me that these values became part of our culture, and it’s something I never want to compromise. It’s essential to the energy of the business. One thing that working for myself and creating a studio has taught me is that I never want to be forced to do something I don’t actually want to do. The autonomy to decide whether or not we take on a project is really important to me, as an individual, but also to us as a studio. Sometimes, especially when you have an agency or a studio, there’s pressure to just keep taking on work, but we’ve been fortunate enough to choose projects that we’re truly interested in and avoid ones that may not align with our values or interests.

Since you founded Special Offer you’ve also had different typologies of clients, is there a plan on who you want to work with?

We have a very focused approach. I have personal goals, but I also have clear ideas for what I want the studio to do and the kind of projects I want us to take on. I have no doubt that we’re going to achieve those things. It’s that kind of blind confidence—which can be both a strength and a flaw—that helps us secure the projects we want to work on. Special Offer has never had an agent or worked with an agency. We’ve never had someone else out there promoting our work or trying to bring us projects. It’s always been on us. There have definitely been times when I wished that wasn’t the case, but in the end, it’s allowed us to maintain control over the projects we take on. Whether in good times or bad, this independence has helped us align our work with the direction we want to go as a business. To welcome the things you want, you have to create the world you envision. It’s something I feel strongly about, and I can get a bit emotional when I think about it. Looking back at my life, especially as I approach 40, I realize that I’ve created exactly the world I wanted. I got exactly what I set out for. Since I was 13, I knew I wanted to be a graphic designer, run my own studio, and do this professionally. I worked hard, and here I am—starting from a small town in Mississippi to having a studio of eight people in Manhattan, working on projects I never imagined I’d be part of. That’s something I’ve never been willing to compromise. I’ve been laser-focused on my goals for as long as I can remember, on what I wanted to do and how I wanted the business to grow. And through that focus, I’ve manifested all of these things into existence. Now, though, I’m starting to ask, “Okay, what happens when you get what you wanted?” I think that’s when you start exploring things like spirituality, family, or maybe even new career paths. But honestly, I’ve been driving toward this for so long, and I’m incredibly thankful for how far I’ve come.

Special Offer’s exhibition identity for Louis Vuitton Visionary Journeys

What’s your relation to competition and pitches?

I try not to focus on other studios. I try to exist in a world where I’m not constantly comparing myself. For a long time, I used to look at the competition, at others who were doing similar work, and I tried to model myself after what they were doing to be more competitive, to sort of “win” or outdo them in some way. I think the idea of competition often brings with it this mindset of being better or worse, of getting the job or not getting it, of winning or losing. But I’ve stopped seeing things that way. What I’ve realized is that the way I’ve started to change my perspective is by not participating in that game. Of course, there are projects we’ve gone after that we didn’t get, and I’ve seen them go to other people. But I’ve come to terms with it, thinking, “That wasn’t the one for us,” and honestly, it probably wouldn’t have been the right fit anyway. Another thing is, I’ve never really been able to clearly define what we do as a studio. It’s not that I haven’t tried—it’s just that we’re really just interested in doing whatever feels right for us at the time. We’re open to exploring different avenues and contributing in whatever way we can to a project we’re passionate about. For example, a couple of years ago, I did costume design for a film. I’m not a costume designer, but I was excited about the project and wanted to be involved, so I did it. I think that’s part of the energy at Special Offer: whatever the project requires, if we want to be a part of it, we’ll do whatever it takes to contribute and help make it happen.

On your portfolio, you present Special Offer as an award winning creative tech company.

From what I see, even from your own production and your image, there’s something quite rare in a design studio—there’s a strong voice, an editorial line, a bit of cheekiness, and self-irony.

Definitely. I think a big part of this comes from typography. My love for typography and the ability to showcase work through it really drove this. Typography needs something to say, and as someone who isn’t necessarily a writer, it’s easy to come up with quick phrases like “award-winning creative tech company”—which doesn’t mean anything but looks great in the typography I’m working with. I’m someone who will sacrifice the words for the type itself. I think I liked the way “award-winning” sat on top of “creative tech company”—it just worked together visually. You’re right, there’s an editorial process behind it. We think about the studio’s mascots, celebrity figures we love for their energy—people like Princess Diana, Marc Jacobs, Beatrice Dalle, or even my dog. It could be anyone, really. It’s about cultivating a culture, a mood board, a reference palette. That’s how I try to define Special Offer: by how it’s branded and how it looks. Specifically on Instagram and in portfolios, it’s really hard to showcase your work if it’s out of context. Rather than forcing it, I didn’t want our Instagram to be our portfolio. I want to keep it light and not make any single post too important. It’s about the collection of all these things coming together to create the world—the energy, the perspective, the attitude—that we want Special Offer to reflect.

Picture by Special Offer

How do you manage both your personal Instagram account and the Special Offer one, is there a conversation between the two?

With Special Offer, I want it to be more distinct. Not anonymous, but a bit less personal, in a way. I’ve been able to lean into things personally that I’m more drawn to, but I’ve always been interested in designers and design studios, not necessarily the personalities behind them. Take Paula Scher at Pentagram, for example. I really understand her practice, but I might not fully grasp her personal perspective on things. With the rise of social media, especially Instagram, it’s become easier to either show or not show that personal side, depending on what you want. So, with Special Offer’s Instagram and my personal one, I think a lot about the intersection between them, where they align, and where they don’t. The two kinds of dance together, especially since I believe there’s a lot of overlap in the audience. Personally, I lean into more radical or aggressive topics on my own Instagram—things that I wouldn’t necessarily have Special Offer engage with. For example, themes from gay culture or more intense, perhaps unsettling imagery, are things I explore more freely on my personal page. On the other hand, for Special Offer, I want to always present really well—polished, professional, and perfect. In a way, my personal account is probably me trying to manifest a life outside of work, focusing on what makes my life unique and how that contrasts with Special Offer’s life.

How do you find balance between your personal life and work?

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve been so focused on work for so long that I haven’t really had the chance to explore personal interests outside of the design and creative art direction world. Now that I’ve built a studio that thankfully has its own rhythm, I’m starting to think more about where I want to go next and what interests I want to pursue beyond work. You’re right, there is more balance now. My personal life and work life aren’t entirely intertwined, and I get to figure out how to bring aspects of my personal life into the studio to energize it in new ways.

For example, next month, I’m shooting a short film, and Special Offer will be handling all of the titles and packaging for it. That’s something I wouldn’t have thought about doing if I hadn’t taken this step myself. Special Offer wouldn’t have gotten involved with this kind of project if I hadn’t chosen to pursue it. So, it’s a nice way to integrate my personal interests into the studio’s work.

Are you getting into film direction?

It’s a project that I’m just interested in trying to execute and see what happens. I think that I would not have the space and ability to do that if I hadn’t a team that means everything to me, but also a studio that could afford me the ability to do that.

How would you describe the current creative market ?

Instagram has, in a way, both birthed and killed certain aspects of it. There’s this increasing emphasis on having a strong point of view and perspective, but everything’s starting to look like an explore page. All design work seems to be following this one dominant style. There’s this one approach I’ve always wanted to execute, something like kinetic typography—a very maximal, type-heavy, digital style that’s sort of punk too. But despite wanting to execute it over the past ten years, I’ve never really been able to do it the way I envision it. The design world, to me, has shifted toward a very hype-driven, loud aesthetic. It often feels like everything is a commissioned project now. Most of the work I see doesn’t feel authentic or spontaneous; it feels like it was created just because it had to be. I think this is something that will continue to grow with late-stage capitalism. Where I’m really focused now is on finding those niche gaps within this environment. I talk a lot about subcultures in my work—like pre-Internet music or punk scenes, where smaller, like-minded communities thrive. These communities were once special because they were hidden away, but now everything is so visible that it’s hard to find something truly unique. I think there’s a resurgence of interest in these more niche, hyper-specific things, whether it’s in photography, filmmaking, writing, or art. It’s all about getting into those really hyper-specific realms. I’m excited to explore that and see where it can go, even if it gets a little scary or weird—it’s that extreme specificity in visual media that really draws me in.

Instagram has been such a focal point. But don’t you think it’s kind of like a dead star? Like, we still see the light, but it’s already burned out.

Even when a platform starts to peter out in terms of engagement, there’s still an opportunity for it to evolve into something more niche. You can still use it to your advantage. I remember maybe 10 years ago, this experimental social app called Peach came out and kind of combined Twitter, Instagram, and Vine all in one—it had this unique feel to it. It was really hot for a second, like Clubhouse or House Party, or even BeReal—all these platforms that blew up for a year and then suddenly vanished. But I would still check back in on Peach while it was active and find people who were still posting and commenting. I think that’s what Instagram is becoming—or will become. Less about mass influence, and more about smaller, more intentional communities. Instagram created this culture where people could chase celebrity, become “Instagram famous.” And now I think we’re starting to see how hollow that feels. Content creation for the sake of content is very different from thoughtful or creatively fulfilling work. And we’ve just become so maxed out on content that people are saying, “I don’t need to see any more of it.” So then the question becomes: “how can I use this platform creatively, in a way that actually feeds me and engages the people in my community who are genuinely interested in what I’m doing?”

Picture by Special Offer

I was thinking, on a side note, that Facebook has kind of become this really niche place for older right-wing communities.

Facebook Marketplace has become this massive thing, and that wasn’t even its original purpose. That wasn’t what it was made for. I think what’s interesting is how these platforms sort of grow these tangential features—these little ecosystems that emerge organically. I also think the platforms themselves will just keep evolving as they need to. If they want to stay relevant, they’ll have to adapt to where people’s interests actually are. Like, the obsession with Reels or short-form TikTok-style videos might not last forever. So then the question becomes: how do these platforms support whatever comes next? And from both a creator standpoint and a consumer standpoint—how does that evolution happen in a way that still feels engaging and useful?

If you could do another job at another time, another historical era, what would it be and when?

Good question. A lawyer? In a modern-day kind of way—not even an old-school one. I’m just really interested in the whole idea of it. I don’t know, maybe it’s because I’m constantly watching crime and legal dramas—like, SVU and Law & Order, that’s basically all I watch at home. I’m always in this mindset of trying to piece together clues and figure out why something happened. And then there’s also this part of me that wants to understand how it would all play out in court. It probably comes from the fact that I’ve never actually been in a courtroom, and definitely don’t want to be in one—but there’s this kind of fantasy element to this whole alternate world. Either that, I’d be a pilot. Pretty much every single person in my family is a pilot. My dad was a pilot, his three brothers are pilots, his dad was a pilot, and even his dad’s three brothers were pilots. So lawyer or pilot. It’s in the blood, or the binge-watching, I guess.

Are there books which have helped you and I’m not talking necessarily from a professional standpoint, that can be personal as well.

I’ve always been really interested in manuscripts. When I was in my 20s, I spent a lot of time reading first-person perspective writers—people like David Sedaris, Patti Smith, obviously—and I think I’ve always gravitated toward books that have a strong humorous voice, even when they’re dealing with more serious or ephemeral topics. There’s something about that blend—humor layered over personal insight—that I find really compelling. I’m really drawn to writing that feels like one person’s very specific, very personal perspective, but still manages to connect more broadly. I really loved all of David Sedaris’ books when I was in my 20s. That kind of writing really stuck with me. But in my 30s, I’ve gotten more into self-help books—especially ones about personal growth and business. I talk a lot about manifestation, and I’ve become really interested in understanding how to actually run a business. If I could recommend one book to someone starting out, it would probably be Profit First by Mike Michalowicz—which is honestly a terrible title, but it’s a great book. It’s all about how to budget properly and make sure you’re spending in the right areas so you can actually grow your business in the direction you want. I also think there’s something interesting about how much weight we put on long-form writing, while short-form writing often gets overlooked—even though it’s just as valuable. That’s part of what excited me about working with the team at i-D—thinking about how short-form pieces, when built up over time, can actually create a meaningful, knowledge-based archive.

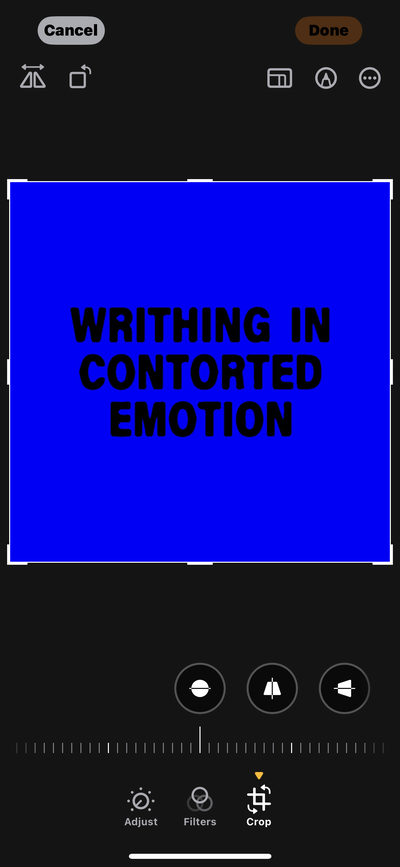

Art Direction by Special Offer for Martine Syms

Is there anyone—an artist or person—who’s helped you along the way?

Yes, definitely. My closest collaborator throughout my entire career has been the artist Martine Syms. She and I have shared a studio space for a really long time, and honestly, I’ve never had anyone I trust more creatively. She’s someone I can bring any kind of problem to—whether it’s creative or personal—and she’s always able to help me work through it. She’s probably my biggest cheerleader, and I try to be that for her too. The way I think about business, creative direction, art—it’s all been deeply shaped by the thousands of conversations we’ve had over the last 15 years. Just going through life and experiencing the world together in parallel. I don’t think I would have done the work I’ve done without being so closely aligned with the work she’s done. That relationship has been so important. In my experience, it’s really hard to exist creatively in a vacuum or echo chamber. You need someone to bounce off of, to buzz with. Even when we weren’t living in the same place, that outside perspective she gives me has always been essential. I’m just incredibly thankful for her in that way.

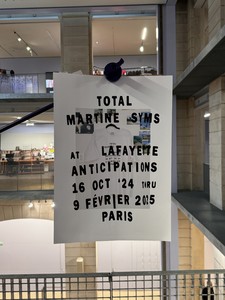

Art Direction by Special Offer for Martine Syms’ TOTAL exhibition at Lafayette Anticipations, Paris

If you had just one piece of advice to give to young designers getting out of school or starting their first jobs, what would it be?

I get paid up front. That’s the biggest one. It’s something I’ve learned over time. As designers, we’re constantly navigating the bureaucracy of client payment terms, and it’s easy to get caught in a loop that doesn’t serve you. You really have to stand up for yourself in those moments and get clear on what your non-negotiables are—those things that will help you do your best work every day. And once you know what they are, you have to protect them at all costs. For us, we were doing website design and development for a long time, and our payment structure was 50% upfront and 50% at launch. But we kept running into the same issue: we’d finish 100% of the work, but then the client wouldn’t be ready to launch. They’d drag their feet, and we’d be stuck waiting for the final payment. So we changed our policy—now it’s 100% upfront. We’re doing all the work, we’re committing fully, and we expect the same in return. And that shift has had a positive effect—it forces the client to be all-in too. It takes two to make a project work: the designer and the client. They have to be as focused and committed as you are. When they’ve put in upfront, the stakes are higher for them, and they show up more. Also, long projects are a trap. If you’re thinking, “Oh, I’ve got a lot of time to work on this,” it’s not a gift—it’s a pitfall. The longer a project drags on, the more it risks losing momentum, clarity, and direction. I’ve learned that keeping timelines short and focused yields the best results. When you’re in a rhythm, decisions get made faster, you stick to them, and the outcome is stronger. Letting someone sit with your design work for too long? It’s a recipe for disaster. Someone has to make the call—and quickly.

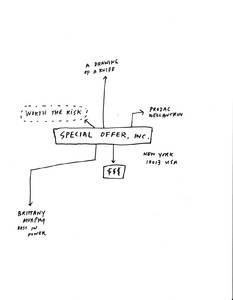

Sketch by Special Offer