Could you introduce yourselves?

I’m Rory McGrath, this is Oliver Knight, together we are OK-RM. We’re a design studio based in London, working internationally in a hybrid way across multiple fields and mediums.

Portrait of Oliver Knight (left) and Rory Mc Grath

What’s your current state of mind, as of early February 2021?

It’s kind of multiple states of mind… all at the same time, fluctuating between extremes.

RM

In a way, I think we’re experiencing a positive shift towards a more feeling based state, more sensitivity towards our emotions and our own personal discourse. Less connection with the outside world. Meetings, yes, but less deep discourse. In that sense, I think it’s natural to have this sense of an alternative view to the present and somehow that brings us closer to our artistic practice.

You used to describe yourselves as graphic designers, are you now seeing yourselves as artists?

This is something we’ve discussed a lot, our belief is that art exists everywhere. Fine art is one aspect of art, but it’s not the only aspect, and at this point I think that the idea of transcending ideas and taking alternative views on the present is very much in our agenda.

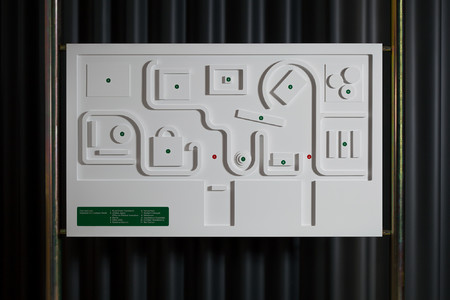

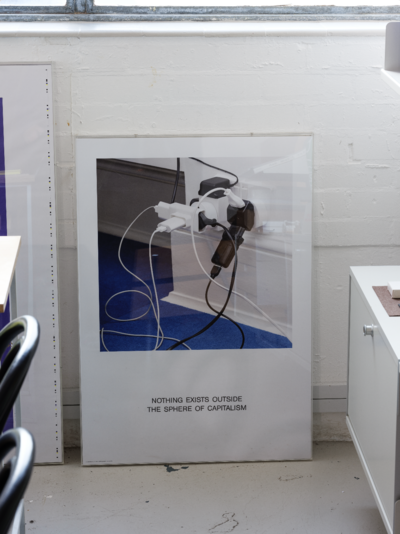

View of OK-RM’s studio

What does it mean on a daily basis? Do you practice art outside commands?

As Rory mentioned we don’t see such a defined distinction. We’re questioning established methods and trying to develop new ways of working as a mean of pushing forward the culture.

Do you mean that Covid and the distances also have an impact on the way you usually collaborate with other artists or clients?

We’ve taken the opportunity in the last three or four months (well, we’ve been thinking about it for a lot longer than that) to actually start to embark on a book project on the studio, which isn’t necessarily a book on our work, but more a book about our methods and ideas. It’s given us time to really reflect on what we do, how we’ve done it, and how we want to do it in the future.

RM

So in terms of how it’s changed us, the crisis, or the condition of the time, I’d say it’s less about Covid and more just to do with how things have shifted in relation to it. Whether they will go towards something else after, I don’t know, maybe this is just a shift. But, of course, one’s thing’s for sure now, there’s a deeper level of discourse. Also, we have to feel and do. We have to be reactionary. In that sense, you have to rely on your feeling because you can’t always build, for example, a discourse amongst others and form a collective opinion in the same way.

in OK-RM’s studio

You met at the university. What were your creative references then?

It’s been a long time! I think the thing that we have is from Bristol: a very special place, a convergent city, you know. It’s a convergence of art, music, culture, mystics, storytelling… We can see the result of that, with music and culture that’s come from Bristol. So in a sense, Bristol was our reference, the culture of the place. We always talk about how, if you can imagine a very openminded art school rather than a design school, we then discovered more pragmatic design history, in things like Grid Systems by Müller-Brockmann in the library, and at that time it felt like an amazing juxtaposition to the culture we were living, and we were interested in the way in which this kind of design craft could help situate and control our ideas.

And now do you have any other references

Over the years there has been a passing flow of references in one form or another. A key thing that we certainly realised, is that we feel working as art directors, that we’re able to almost re-enact or perform certain references rather than saying: “I’m inspired by the look of that”. We didn’t realise it before but we’re doing it anyway, and I think it connects very well with the time that we’re in.

For example, let’s say that you’re working with a specific type designer or typeface, you kind of embody his character in the form of a book, for example. So we take influence from all over because we artdirect attitude and approaches.

RM

That gets more into our methodology for specific references, just to situate us more specifically, conceptual art is like our underpinning at this point in time key names like Joseph Kosuth, key curators from that era like Pontus Hultén – who worked at the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, the Pompidou for a while, and the MOMA – and he has specifically been a very big influence. Not only because of the artists he was working with, but also because of the way he “art directed art”. That can also be seen in the practice of Harald Szeemann, especially seen in his work for documenta 5. There for example, he commissioned Ed Ruscha to design the cover of the catalogue and poster.

It’s not so much about aesthetics, it also has to do with understanding context, and understanding the discourses that were around and drove that work at that particular time, and why it happened, this drifts from reference to research. For example, Sol LeWitt’s text Sentences on Conceptual Art is very important because it really depicts his manifesto and his reasons for working in that way. It’s easy at the beginning to love the look of the grid that he uses, but ultimately, intuitively when you’re young, you can find things that just are “beautiful”, but then you want to understand why.

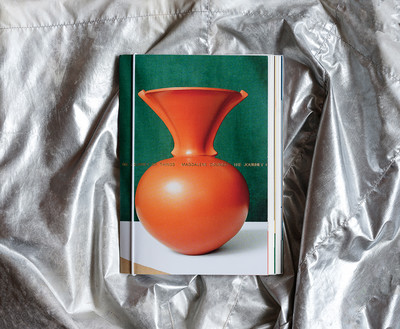

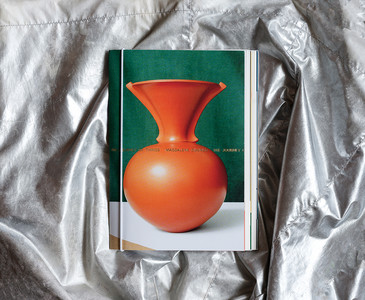

Jean Tinguely: “Méta”, HULTÉN, K.G. Pontus

You worked separate ways after the university and before OKRM. What were your experiences?

We both worked for about four to five years, we learned many things that were useful to preparing us. Specifically during my time in London, I was involved in the visual identity for the Barbican Centre and in New York I had the opportunity to work across projects for Harvard Art Museum, Vitra, Prada, and Nike.

OK

When you’re starting something it’s always useful to have a counterpoint, or something you’re rejecting. I think we definitely started with a strong realisation that we needed to do something differently than what we had experienced. That’s not to say that the experiences weren’t valid, just that we were consciously making a departure from there.

Among the other things that you learned that you were sure you would never apply again, what were they?

We both realised fundamentally that we’re interested in being part of content and culture. In that sense we really appreciate systematic design principles, but we wouldn’t ever want to have that oppress the potential for the genuine engagement with ideas and content. And we don’t really believe in the answer always being corporate identity, especially for art, because we appreciate so much the variation within art and its relationship to its communication and other contexts. For example, in Pontus Hultén’s or Willem Sandberg’s work, the art direction of art and how art can resonate from the space of art, the gallery, outwardly, with coherence and simultaneous ideas is crucial to their success in progressing culture.

We wanted to ask you how you make sure that you maintain a good level of creativity. From your answers, it seems that you’ve developed a more artistic approach in your practice with the Covid crisis.

In general, I suppose there’s always been this kind of artistic practice, but we’ve just become comfortable with it and our identity in general.

OK

We are getting to the realisation that it’s the aspect of our work that we’re more interested in pursuing, or just in trying to make sure that the opportunities we decide to bring into the studio are the ones which allow us to focus most in that area.

Our Happy Life Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism, exhibition 2019

Our Happy Life Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism, exhibition 2019

We planned on asking you: what do you think your creativity will be like in 10 years? It’s a better question for a studio that’s just taking classic relationships with clients, because they have to maintain that level through orders.

But it’s a good question. We work a lot with Jack Self, and he’s a very important collaborator. He always has a special way of talking about his career in 10 years plans. As a way to kind of conceptualise a career, or a project, a career as a project, and I think that’s something that we also tried to do because it’s an interesting exercise. We do talk about this kind of idea of where we are headed, what’s the project, what’s the concept of the studio. So, thinking ahead: “What will our creativity be like?” Hopefully still exciting, but I think the work will ideally go more and more into this space where we’re able to work to define context where we are able to invite others in to work with us and each other – whether that’s a school, art space, brand … its not clear, but as long as there is the opportunity to question, collaborate, and merge disciplines, ideas and possibilities in general, we will be motivated.

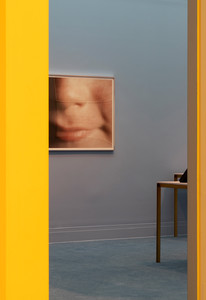

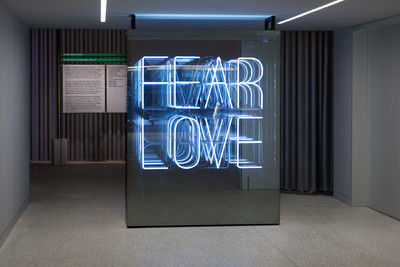

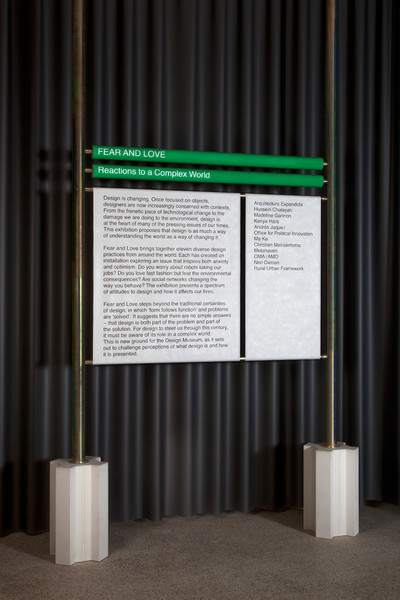

You’ve already done some projects which were close to that, such as Fear and Love, at the Design Museum. You designed the space, the graphics, but you also had work there, “Fear and Love” in neon lighting.

That’s a good example where maybe there was a cross roads of traditional roles and responsibilities. We developed a really strong conversation with the curator Justin McGuirk, so when he became the chief curator of the Design Museum he immediately offered us a broad remit to question broadly speaking: “How do we communicate this idea of the curatorial premise before there were any works commissioned, or anything?”.

OK

I think it comes back to your previous question, a kind of definition between graphic design versus artist, in this space which we’ve always found had a limitation of people’s expectations of what graphic designers should be or should do. We have found in the past that institutions can create overly specific design limitations that are not progressive before there is any dialogue. What we do is not always within the limited expectation of the role of graphic designer, we prefer to be involved in the whole conceptual process before the actual execution of a design can take place.

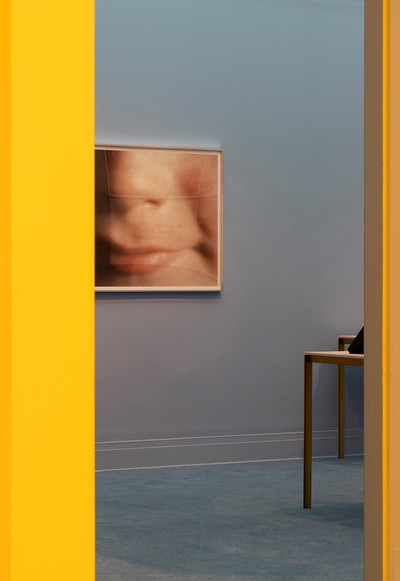

Fear and Love exhibition, Design Museum 2016

Fear and Love exhibition, Design Museum 2016

Fear and Love exhibition, Design Museum 2016

Those questions also have a strategic dimension. It seems to us, from the outside, that we’re seeing a very good strategy here. What is your studio model at the moment?

Well, strategy is a funny thing, too. It’s a bit like graphic design: no one knows what it means. Because conceptual art is strategy, it’s only strategy. If you read Sentences on Conceptual Art by Sol LeWitt, it’s a strategic document that drives his whole endless artistic outcomes. So, in that sense, we consider strategy and conceptual thinking very aligned, and that’s basically what we do. We are absolutely strategic.

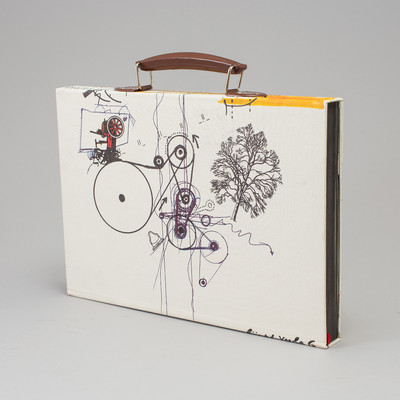

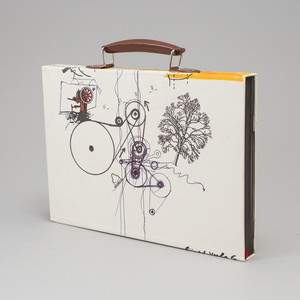

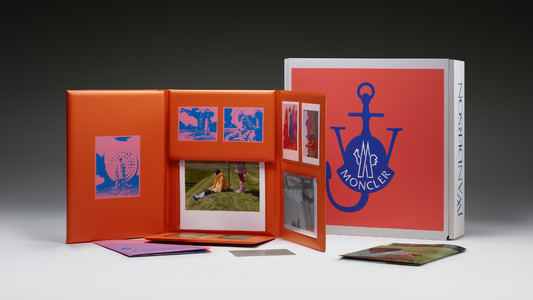

The Inflated Archive (an exhibition in a box) is an object made in collaboration with Jonathan Anderson and Tyler Mitchell to launch the JW Anderson collection for Moncler, 2021

The Inflated Archive (an exhibition in a box) is an object made in collaboration with Jonathan Anderson and Tyler Mitchell to launch the JW Anderson collection for Moncler, 2021

I was going to ask you about the strategic references you have, but they’re in the artistic field, like you mentioned. Do you have any other strategic references?

For instance Designing Programs and Grid Systems from the noble Swiss modernists who created a series of very precise strategies about the craft of handling complex information are really useful when it comes to understanding the strategy of consistent and efficient form.

There’s a lot of strategy that’s embedded in other forms of art, like performance art. Trisha Brown for example: her work is also conceptual art, but it’s also performative, so it talks about the ways in which things can be, and move, and become a whole performative scenario. So the strategy in that sense can be about how control works over improvisation, for example.

It’s a good point. It’s this idea about institutional craft, which is another way to talk about strategy. And it’s about how you can articulate ideas within a group, or open up spaces, or thoughts which other people hadn’t noticed, and so you can work into that.

RM

And somehow get closer to this idea of the epicentre, the area within an institution where decisions are made.

OK

We see the role of the graphic designer as having the potential to be very much in the middle of all the decisions. And if you can negotiate with those around you then you can… I mean, that’s the strategy isn’t it? It’s a negotiation. It’s about relationships with other people that make the decisions.

RM

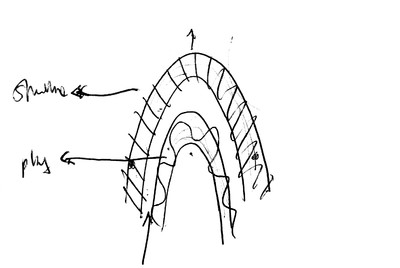

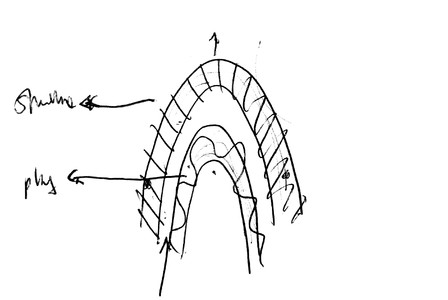

We also work a lot with progressive architectural practices who think like this as well. In architecture there’s 51N4E, whom we worked with at Newrope in Switzerland. Freek Persyn, who’s the director, talks a lot about “designing in dialogue ”… This is his strategic model, and there are discourses around this: models and diagrams and literature, just to deal with how you get all the participants, or actors to cooperate towards one shared goal.

Again, we’re back to the idea of collaboration. Would you say that this was your strategy from the very beginning when you founded OKRM?

Yes, OK-RM is all about collaboration. Even in the name. Our first business card design was two cards, perforated down the middle, one for me and one for Oliver. We underlined this idea for a long time that we are explicitly a collaborative practice.

OK

We still do!

RM

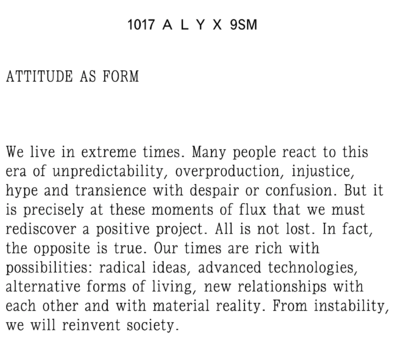

Yes, but at some point the word collaboration became sort of buzz word, and we sort of softened the word in our work to distance ourselves from its misappropriation in marketing fields. Now we talk more about the synthesis and symbiosis of work and practice. There’s a text which summarises our approach really well which we wrote with Jack Self for 1017-ALYX-9SM, called Attitude as form.

Introduction of “Attitute As Form” writtenby Jack Self and OK-RM for 1017-ALYX-9SM

Check full text here.

Visual identity and Art-direction for 1017-ALYX-9SM

Visual identity and Art-direction for 1017-ALYX-9SM

I guess that was the idea as well behind your publishing imprint InOtherWords, when you created it, to have this kind of collaboration, but was it also strategically thought out?

The strategy of InOtherWords developed as time went by, but it immediately presented itself as an opportunity to open up a new space for us to work into. And without having sat down and created a business plan, we knew that it would open up opportunities and a slightly purer space for collaborations with artists and directors, whoever else we were working with.

RM

It was also strategic on a level of how do you govern a body of work. The thing with graphic design practice, in general, is that our work drifts into many spaces. Ultimately you can’t really see it as a body of work easily, there aren’t so many spaces for presentation. So we realised that we also wanted to create a governable body of work. The publishing allows this to happen. We also wanted to strategically question, but also perfect, a financial model that would allow and support the work to take place in another way. So by owning the economy of the work, we can start to generate opportunities for ourselves, and we don’t have to be the victims of budget issues, which are very passive when you’re a designer relying on commissions. We can start to be a bit more entrepreneurial, which is useful.

Preparation F19, photography by Esther Theaker, commissioned by Alyx and published by InOtherWords

‘The Journey of Things’ by Magdalene Odundo published by InOtherWords

Preparation S20, photography by Esther Theaker, commissioned by Alyx and published by InOtherWords

It seems like a clever space as well to attract some cool fashion brands who have a problem with content, and even more since the Covid crisis as some want to reinvent themselves and provide content beyond fashion. We might be postrationalising here, did you have that in mind?

That was more of a lucky thing, more like positive luck. As much as we like to strategise, on that level… we can’t. Because we are very against being contrived or too planned. We faithfully appreciate publishing culture, there’s a real danger in design initiated publishing imprints to become token. We want to create a genuine cultural space and it’s great that it’s able to be a space of convergence.

OK

I think it coexists perfectly with OK-RM. Without InOtherWords, OK-RM is less strong, and without OK-RM, InOtherWords probably wouldn’t exist. Together, they’re a very strong entity, and of course the more projects we get under our belt with InOtherWords, the more appealing that is to many other people who want to place themselves inside this little culture that’s being built.

‘Show in a box’ JW Anderson, S21 (Edition of 500)

‘Show in a box’ JW Anderson, S21 (Edition of 500)

We were talking about fashion, because I think you’ve got some good projects with fashion coming, and some already existent. What’s your feeling towards fashion at the moment?

Fashion is a context. It’s a platform and a context for us, primarily. I think we’ve been lucky enough to work with designers and brands that really appreciate that too. There’s a mutual understanding about that, there’s often a conversation about the clothes – we don’t ignore the fashion itself – but what we’re really doing is working into a cultural space.

Junya Watanabe 2020

You’ve developed relationships with new brands. How does that happen? How do you handle the business development? Do you have someone helping you?

No, not really. We’ve met a lot of people over the years so we have a lot of connections out there and projects come in, we don’t really seek work. With InOtherWords, we’re constantly in dialogue with artists and people we like to work with, and sometimes projects happen.

RM

It doesn’t make sense for us. Strategically, it doesn’t make sense, I think we need chance!

Have you ever considered having an agent?

Yes but for now we decided not to. We had many conversations but for now it works well without representation.

What’s the studio model at the moment? How many people?

We have six people: one project manager, everyone else is designers – Ollie and I are designers and strategists!

So you’re still designing?

Yes of course! We have to design, we want to design, that’s important. We try not to design on the computer only. We design conceptually so there’s a lot of discussion. We’ve always been computerbased. Obviously we also work with our hands too, like in terms of printing. We’ve always been very able in terms of craft. You could say that it’s our model, internally, but we also have a lot of consistent collaborations around the studio. So, in a way, the studio is much bigger than the core team.

NEWROPE is the shared endeavor of rediscovering a territory, both as a shared history and a common futur

NEWROPE is the shared endeavor of rediscovering a territory, both as a shared history and a common futur

It’s like a platform?

Yes, we work consistently with architects, writers, curators, programmers, and artists.

The way you explain your process, relationship to clients and institutions it doesn’t seem very compatible with the process of competitions. Do you sometimes still do some, or do you refuse them?

We don’t pitch, and it’s not an arrogant thing, it’s because we aren’t good at it!

OK

The ethics also are a key issue, but if there is a good reason or an important reason why a competitive led approach is crucial, then we are open-minded in theory.

All the people we interview seem to have a similar point of view: we’re less good when we’re in a pitch, and the outcome will not be as good.

That’s 100% right.

How do you handle your communication? How do you think about your Instagram, your website, the conferences you go to, answering the request for this interview?

I would say that we’re quite unsuccessful with that aspect of our work, but maybe everybody feels that way, it’s hard for us to perceive. As for Instagram, we have it because we feel that we have to, but we definitely don’t strategise it. We manually just figure out what we want to put on there, we treat it as a kind of portfolio, which is fine, because it is what it is. We used to take our website very seriously; it really had a function for the studio to clarify our approach and see our work in one space as an archive. In the years up until three or four years ago it was crucial because we had to establish ourselves as well. Now it’s not up to date, it’s been temporary for about a year and we are trying to find time to update!

Is your relation to self-promotion to control it, to have a proper discourse in place for someone who wants to pay real attention to it, while Instagram has this attention span problem?

If our work is to exist culturally and therefore be part of “real life” then it should only be proven by how it operates within culture. These shop windows, this is not culture, it’s a link to culture but it’s not proof.

OK

That’s a very true point you make there. You talk about Instagram being attention deficit, but you know the idea of a press release where people just copy/paste the paragraph and you see it on one hundred different posts… There is that severe lack of interrogation and depth.

RM

And empathy for others, empathy for an audience that actually wants to participate.

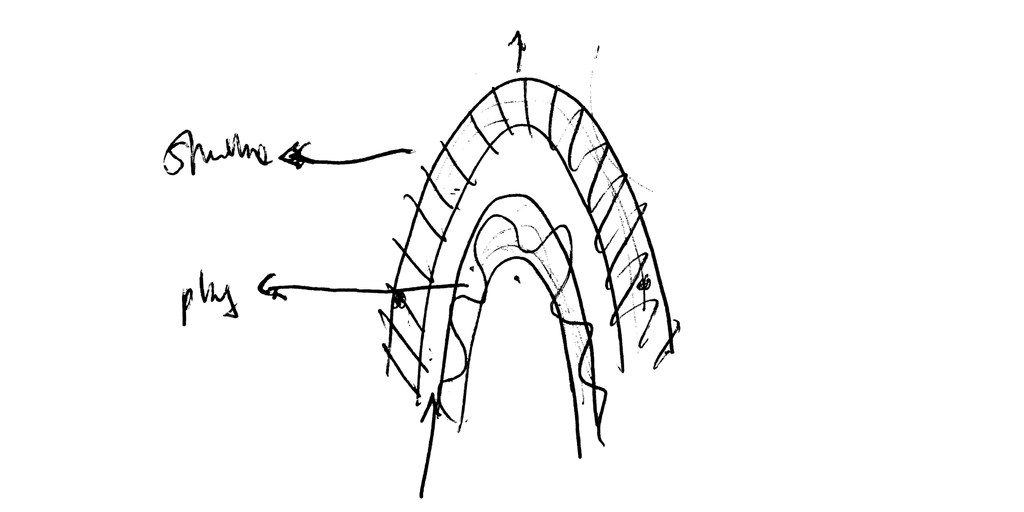

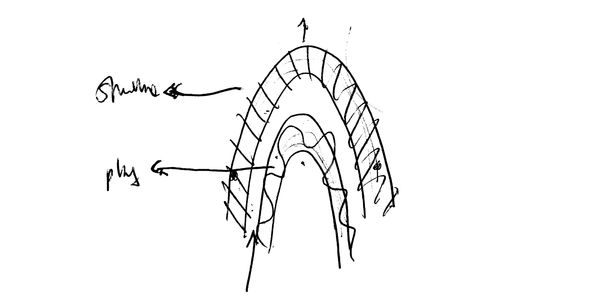

Sketch by OK or RM

What do you think about the current creative market? If we dare calling it a market after the conversation we’ve had.

There are some amazing projects happening right now, within our field. On the level of younger friends of ours, there’s a sort of craft and creativity on a simple, primary level, whether that’s also crossdisciplinary, like someone starting to explore fashion or music when they are trained in a graphic design programme. There are some really positive projects, like somebody said to me the other day: “When everyone is on their knees, like the bigger players, it’s an opportunity for others to rise”. So I think right now, we’re seeing a lot of positive progressive activity from younger makers. I don’t know about the marketing stuff, because I guess there are a lot of damages in the market, in calling the market the industry of things. We have to change, adapt and develop, and this is the opportunity. I guess bigger, heavier entities will take a longer time to do that. Creative practitioners have always been agile, moving with the times, we call this the flow! In a sense we’ve always had to be reactive and agile. So, I don’t see any reason why that shouldn’t encourage positive creative activity.

OK

There’s a lot of questioning going on of status quo at the moment, and that can only be a positive thing when it comes to the potential for creativity. That’s the most optimistic thing. There are a lot of fashion projects that are starting to do that, and also we see developments in the way architecture’s being practiced and questioned. Architecture in many ways got hijacked by property developers for so many years, but in many cases it’s really taking on a more cultural, social, political role now, at least in our viewpoint. And that also happens in fashion, and I think in art, too. It’s a fertile time I’d say!

In OK-RM’s studio

When you’re observing younger talents, graphic or type designers, is there anything you like or anything that makes you think: “Oh, be careful with that! »

Yes, so many things! We’ve just finished an interviewing process for a designer to join our studio, so we’ve been meeting a lot of them. We had hundreds of portfolios and then we met some tens of people, so we’ve really been through a very close proximity to this. As much as it’s positive, it also feels melancholic. Because there are a lot of victims of superficial aspects of service culture, stylistic tendencies, like fables, a lot of acting, a lot of insincerity. I think all of that is driven by some kind of fear, probably economic fear, or a lack of proximity to culture and things that can be believed in. I think that’s a real problem of design schools becoming too much these institutions that are impenetrable and therefore uncultural. I would say that it’s a systemic issue at this point in time. And we have the obligation, in practices like ourselves and others, to try and bring a kind of positive message and optimism about the potential of what we can do. Because it’s possible that anyone can do it, given the right tools and the right opportunities. I also don’t think that relies on money or privilege because, actually, design schools are so often unfunctional, and unpractical. The alternatives need to start to be put on the table: collective learning, network learning, having the support systems, more flattening of the hierarchies that exist in design. We need to be more available for people to discuss things with us, and share our experience.

We feel that a book is the right way to do that because it’s easier to reach a number of people, but we also intend to try to tour, and visit, and try to hold small talks and classes.

I think that if everyone tries to just open up a bit more, that would help. We feel quite passionately about it because I don’t think that it can continue like this. There are going to be a lot of nomads… I don’t know what people do when they’re untrained, and in a way, deluded by what they think a designer is, or what they think that role is. It could be that there are too many people trying to be designers, too. Maybe society in general has to think about how to prepare young people to perform positive roles.

OK

When you said it’s a systemic issue, I think that it probably is. I say this in relation to the fact that there are so many designers coming out of schools, and there aren’t that many places for them to go which are actually the kind of places that they imagine themselves in. When you have three years of freedom just exploring cultural ideas, something which is deep and meaningful, and you end up in a branding agency, or an advertising agency, it’s like: “Ugh, I’ve come out of this thing, and now I’ve been dropped into an inescapable pot!”. The one positive thing to take from that is that designers don’t necessarily come out of university and have to go into designing. You see graphic designers starting fashion brands, becoming writers, teachers, artists… That’s why we’re more comfortable with graphic design as a craft to deliver an idea. And I think that designers need to be people who believe in their own ideas, start their own projects, use their design skills as one of the things that they do to make that happen.

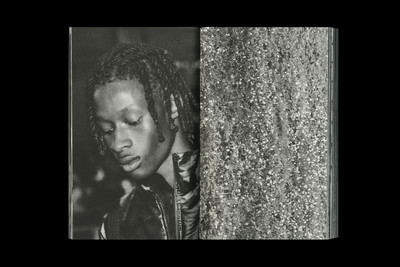

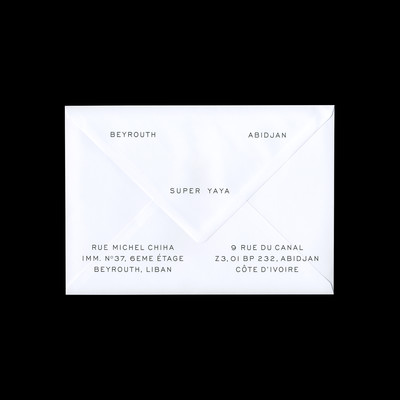

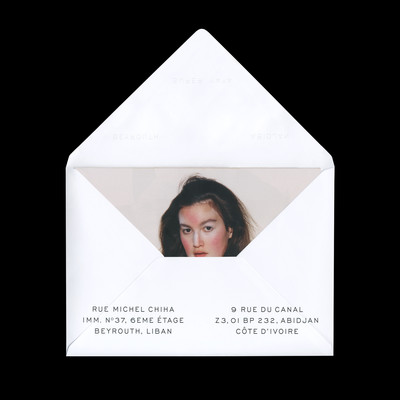

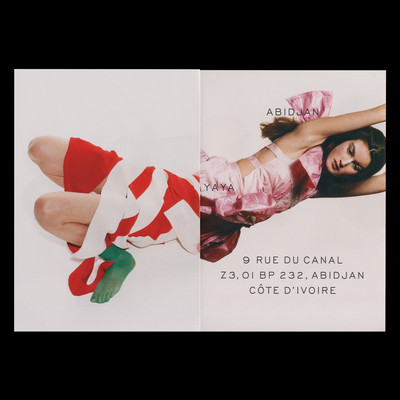

Super Yaya “Dakarta” SS2020 an edition in an envelope

Super Yaya “Dakarta” SS2020 an edition in an envelope

Super Yaya Booklet

You taught a bit, didn’t you. Do you still want to teach?

Yes we do, we currently run a yearly design module at the ISIA Urbino in Italy. We have ambition to do more, we just need the right place and opportunity. But in general, I think it would be essential for us to dedicate more time to that.

You’re saying that this positive philosophy you’re sharing kind of exists right now. Do you think it really does or that it’s trying to emerge?

This is a tricky question. I know that our minds can expand to see a whole situation at once, and I know that the news and so on perpetuate this sense of a whole problem, but there are many people so if we all just do something small, seemingly insignificant, eventually it will make a difference. I strongly believe that what we’re doing is creating a difference and that’s probably through the progression of culture, even if that’s in a micro way.

You’ve mentioned a lot of books and writings. Are there any others that you can think of that help people in their development? Ones that helped you?

There are some classics. I always say that What is a Designer by Norman Potter is a good one. Bruno Munari’s Design as Art. These are simple, humble works. Reading fiction is important. It’s important not to only read things about your subject. I’ve really been enjoying Zadie Smith recently, mainly because she’s amazing, she works with metaphors so well. It’s like a different level that you can go to, where design isn’t capable. Only writing can take you to that level.

RM

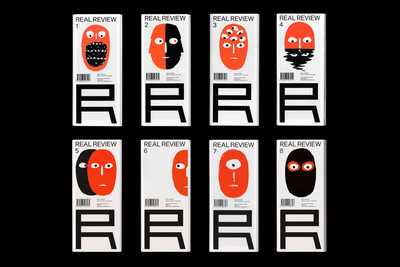

I think that’s a good point, too. The Real Review – you must read that, its a gem of a periodical.

Real Review covers

Real Review

We have one last question: what is your advice for young people wanting to be graphic designers or independent creative?

It would be nice to answer that sharply because it relates to what we talked about„ but I think that in a way, the best advice that we give is just really take your time. I know that we’re in crucial times, and there’s a real urgency, and we can feel it. But still, when you’re young and embarking on a career in design, especially in education, you should definitely take your time. Don’t see productivity just as a way to gauge work. It takes time to understand what’s happening around you, and that’s something you really only learn when you’re older, right? Annoyingly. Run around in circles for years, then…

OK

I think this is becoming more and more relevant now, but “to find a project”. I don’t mean a commission. What is it that you want to spend your life working within? I think it’s one of the big questions for design, because you can be a designer on millions of different types of projects, with different messages. What is it, as a designer, that you believe? And that’s irrespective of projects, of commissions. It’s more about a discipline within which you operate. Because design is a tool at the end of the day.