Hello, could you introduce yourself?

My name is Joris Poggioli. I’m an architect and designer. I’m 33 years old, and I’ve been in Paris for 15 years.

Joris Poggioli

Joris Poggioli’s logo

And how do you present your work? Your practice?

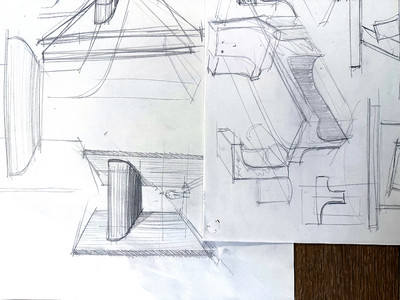

Maybe we can get back to it later, but I have an uncle who is a sculptor, and I worked in his workshop while studying architecture. That really gave me my own twist. Today, I am quite convinced that I work like a sculptor, whether in architecture, design, whatever the practice may be. In any case, the result I’m looking for is a sculpture.

And in interior architecture, it’s more complicated, isn’t it?

Much more complicated, but it’s sort of an area of focus for me. And I always say at the studio, “Think about the final feeling you’ll have. What’s going to happen when you take a walk through that space? What is it that you want?”

My phone is sort of like my second brain in terms of images. I am very visual, and as soon as I see a “crush,” a thing I like, that touches me, I take a photo of it. At the agency, I always say, “Design something you want to capture in a photograph. As long as you don’t want to take a photo of it, it’s still not right.” Sculpting your space, playing with light: it’s all very connected with sculpture.

Orfeo Desk, 2020

You say “agency,” so you present your entity as an agency?

Workshop, studio, agency… It sort of depends on the day, on whatever mess is happening inside.

What is your state of mind right now?

It’s really rather good. We have worked very hard, and today I almost feel like I’m on a springboard where you can fall off or jump super high. It’s exhilarating but also a bit exhausting.

This may not be the first time, but do you feel like you’re at a turning point? Why?

I think of it more like a staircase. You work really hard all along the way, and at a certain point, you step up. And now I feel like the step was higher this time because we wanted it to be. These were goals that we set for ourselves, which we achieved. Now that we have these as reference points, the question is, what do we do with them? It’s super important because if you get there, it can take you a long way. If you miss a step, or if you’re not proud of it, then that is much less the case, which communicates poorly, you know?

Among the projects you’re alluding to that can lead to this “step-up,” are there certain ones in particular?

I’ve had three or four. There is this hotel architecture project. There’s my own apartment. There’s a publishing and design label I’m launching called Youth Editions. And there’s Totem, which I launched not long ago, which was like starting a production company. And now I am working for this kind of American design giant.

There was a need to take a big step forward and say, “Careful, let’s not mix everything up.” We were selective. Personally, I’m becoming more of an artist. At Youth Editions, there’s the idea of accessibility because I’ve always loved popular design. With the Americans, it’s a way of doing more upscale production.

IDIA coffee table and SIRIO ashtray, 2019 Photo: Gabin Roux

Who are the Americans?

It’s called Restoration Hardware. It is the number-one luxury furniture brand in the United States.

And what are they going to produce? Other designs that we haven’t seen yet?

There are the first pieces that have already come out in three of their galleries and several collections that are on the way.

You were telling me that you got to product design through sculpture, and that’s also how you came to interior architecture. But how did that part happen? Your studies? What was your path after getting inspiration from your uncle?

I wasn’t necessarily interested in design. I was very interested in architecture. It was really a thing for me during my architecture schooling. I was the guy who finished class first and met with the professors. I was already basically working for them in my first year, and I would go see them saying, “send me books.” I finished school after five years and ended up winning two competitions. I won one competition for ConstruirAcier in my fourth year. In my fifth year, I had a friend who suggested I do the Audemars Piguet competition.

What was the first competition you won?

It was the Wilmotte competition with steel. The second competition, in my fifth year, was for Audemars Piguet. We can come back to that. Because it was really foundational for my career. But in that competition, we came in second place in a contest where I was up against all the guys I was sending my internship applications to. Then, in my fifth year of school, my friend suggests we partner together. And so I graduate and start my agency in my name. I worked for three years, and it turned out to be horrible for me. What I had seen in architecture was Le Corbusier, designing houses.

Ah, so it was HMO (Fr: Habilitation à la Maîtrise d’Œuvre – En: Project Management Authorisation) architecture?

Actually, I was doing interior architecture, and my father did not think highly of interior architects. So I was taking evening classes at the Grenoble National Higher School of Architecture. I did three years of that, and my goal was to move on to a fourth year in HMO (Fr: Habilitation à la Maîtrise d’Œuvre – En: Project Management Authorisation). That was my ambition, except that, in reality, the more I did my evening classes and the more we were going towards multi-unit housing, you know… those sorts of 1980s visions of architecture… Collective housing, regional governments: that’s always been a real pain in the neck for me. In architecture, I don’t think about the building; I think about the person. I start drawing, thinking… I wake up in the morning; what’s the first thing I see, the first thing I touch, the first thing I feel? And instead of starting from the outside of this box we put people inside of, I start from the person and design around them. So one day I have this revelation. I know what kind of architecture I want to do: I want to go through the interior, through interior architecture, to break the system.

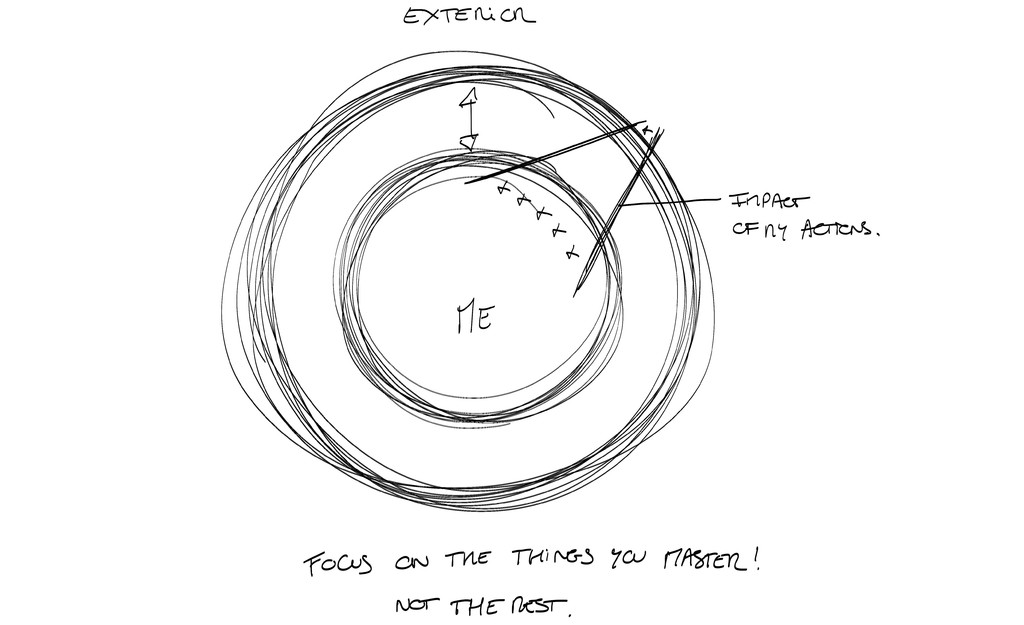

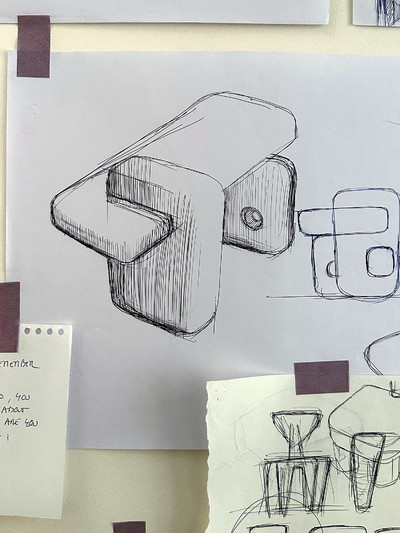

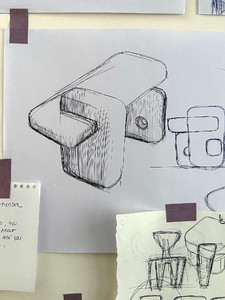

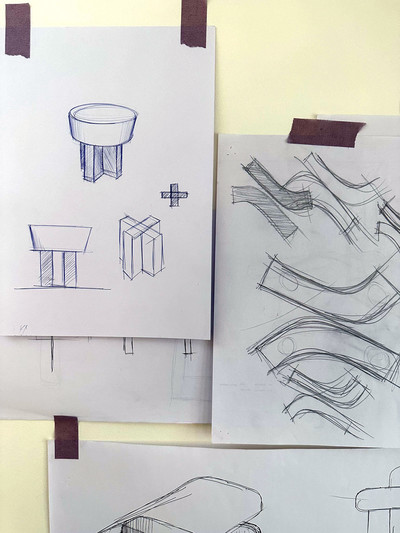

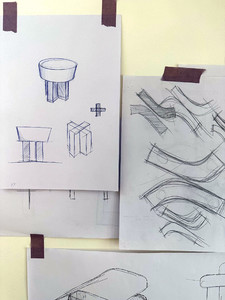

Sketch by Joris Poggioli

And then what?

And so during my three years at the architecture agency, where I got my big ambitions, I discovered big thinkers, Adolf Loos, etc. I would end up choosing a wallpaper or carpet, and a client would say, “Ah, actually, I talked with my friend, and actually, no, we don’t want this carpet; we are going to go with this wallpaper.”

It was depressing to me, and there came the point when I thought that I was going to work at MacDonald’s. At least no one would ask me to use my brain and at least I wouldn’t pollute my art. And before leaving, my father comes to me one day and says, “You’re a fool! You have this thing within you. Try one last time!” And the idea—my one last thing—was: “Can I build a house and show what I can do?” It was too complicated in terms of money so I started doing “micro-architecture” and that’s when I started designing.

And what do you mean by “Micro-architecture”?

They were finished objects. Either you like it or you don’t, but, in any case, it was a vision of a house, how you treat light, how you touch, you know?

And how would you do that? Using materials? Or with 3D?

All the pieces came to me. I was drawing a lot. A lot! It always started with drawing, then usually sculpture, then 3D, and lastly manufacturing with skilled artisans.

VILLA TOTEM, Dinning room, 2022

You started to name some references. When you were a student, what were your visual or artistic references?

I’ve always been very moved by Tadao Ando. I was obsessed with that notion of how to treat emptiness. That guy comes in and says that architecture is also space. And that space, it isn’t empty. In fact, it’s the projection of your brain. All your ideas need space to be expressed. And the second one is Le Corbusier, who established very reassuring foundations: you have to do this, this, this, and this, and you’ll be a good architect. And that’s what he did. But behind all that, at the end of the day, he was a totally crazy artist who was capable of creating the unthinkable, the unexpected, the artistic. He took those two worlds and created a great explosion: Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp. It’s incredible.

And there was a third one you mentioned in architecture?

Yeah, Adolf Loos because of the Raumplan… Each room must match what it is used for. And if the exterior ends up being aesthetically monstrous, it’s not a huge problem. Because inside, in the bathroom, you’ll have a low ceiling, and you’ll feel warm because it is very humid. I mean, there is total humidity because you’re nude, so you don’t need the same thing as in a living room, a lounge, or an entryway. So he helped to reinforce my ideas.

You were talking about “micro-architecture.” Is that when you started to define your approach? Or your style?

Yes, I think so. My uncle was obsessed with obese women and made tons of sculptures of them, so there were hundreds of sculptures around me, women with huge, generous curves. A little like Gaetano Pesce, you know? There was this light that was coming in from everywhere all the time. I think I grew up in it. I was obsessed at the time. I was a professional rugby player. So in the locker room, I had only—

Sorry, professional rugby player?

Yeah, it was my first job. I was a pro.

But outside of school?

It was in Grenoble. Actually, I started with business school, which lasted six months, and I left. I continued playing rugby for a year and quit when I started architecture school. When I went back to architecture school, one of the directors at l’École Bleue said, “No, we love your profile, but we want you to continue [with rugby]” at Stade Français, for example. I said, “But do you know how many practice sessions I have to attend every day?” It was one or the other. I always knew I could have been a great Pro D2 player, average in D1. I would never have been an international player. I played with international players on my team, and I saw that there was definitely a gap… And why was I talking about that? Oh yes, I was doing sculpture, and I was seeing a lot of bodies. And that approach, with the light coming in on those robust, curvy shapes, that helped me.

You never play anymore? Maybe it’s not a sport you can just dip into casually.

I’ve tried, but… I’m a humble guy, and it’s not really an ego crisis for me, but… Now I play with friends, and I get a bit pissed off, you know? Otherwise, you don’t just get back into it by training once. You have to go back to doing this and that… You have to go running and everything, it’s not possible.

We were talking about creativity as well. Did you have to draw or do 3D? How did you project your ideas at first? I’m returning to the question about the material versus the unreal…

There are three main tools in my profession. The first is obviously drawing. Drawing is my language. Le Corbusier said, “I would rather draw than talk.” This is clearly the case for me. But you can be fooled by a drawing. If I draw you a chair, I will have the dimensions in mind, so the chair will not be completely crazy. It might be a little too wide, a little too deep, you know. And so you validate it either through sculpture or through 3D, and, depending on the shape of your chair, I’ll prefer one or the other. Like clay, pure clay. You know, you take a block of clay and sculpt it, like with cars. And if I’m looking for something else, that chair, for example, it’s gonna be very complicated to do as a sculpture, it’s better to use 3D.

FRANK desk, 2022 Photo: Émilie Krengel

Your relationship with work seems rather… not workaholic, per se—I don’t judge—but it seems very intense. Is that still the case?

You can even say it outright. I’m the kind of guy who feels guilty if I don’t work.

What did that come from? From rugby practice? From school?

I think it comes from a lot of things. It comes from my family sphere. From a father who was up every morning at 5:00. It comes from a passion for…

What does your dad do?

My dad is a locksmith.

He gets up at 5:00 every morning?

Oh, yeah, he’s the first to work. For example, in rugby, I was the first to get to practice and the last to leave. It’s a passion, actually… My brother and I love entrepreneurs. We love books by entrepreneurs, personal development… I’m a Tony Robbins fan. I think if I hadn’t been an architect, I would have been a coach. And in that, you say to yourself: I want something, but do I really want it? And if I really want it, how do I get it? And as soon as you put everything in place to get it, the rest is just a matter of priorities.

You put in the hours. And creatively, if the rhythm is getting intense, do you ever have periods when you have less inspiration than others?

Yeah, a lot of times. There are actually three things: the job, the creation, and your family. You have to be careful to find the balance between the three. I was lucky to realise very early on that you could quickly become an architect who let himself become overtaken by his projects. That is to say, tomorrow, you offer me one, two, three, four, or five projects. Financially, that’s cool, but creatively, not so much. If first, you see the money, the opportunity, you’re gonna get into it, make your schedule. You’ll get crushed by your work, and your creativity will vanish. But I think there are these kinds of moments where you have to say to yourself: “Okay, I need this time.” Sometimes it’s on Saturday morning, Sunday morning. I have to work that in with my family and my schedule. But for example, in the office, sometimes I say, “Monday afternoon, we’re going to the library. We are closing our computers. We’re going to open books, and I want us to come back with material, with food.” And I think if you don’t give yourself enough time, you start to fade, and your agency becomes less interesting. Everything becomes less interesting. We need inspiration.

CLEO screen, 2022 Photo: Giulia Fassina

CLEO screen, 2022 Photo: Giulia Fassina

What were you doing five years ago? Where did you think you’d be now?

That I would be right here.

Then you’re on schedule. But do you never set your sights too high?

Yes… yes, I do. In fact, the idea is to give yourself very high goals without temporality. Concrete goals with little temporality. Well, that’s my technique anyway. My goal is really to inspire. It is in no way a competition or a war. At least, I don’t see it that way, but you inspire some people more or less. And if you really want to inspire, to be in the top five in the world, well, you have tons and tons of little boxes to fill. You will start to inspire your neighbourhood, you will inspire your street, you will inspire your city… And the sort of pyramid there is to climb, we’ve fallen down many times. But, for the moment, I feel we’re not doing too badly. There are lots of things that could be better, that can be improved, but I come from a gallery generation. Today, any guy in his living room who does 3D launches and sells his work on the Internet. My generation is the gallery generation: Rue de Lille, Galerie Kreo… You knock on the door, you leave your portfolio. If Cinna or Ligne Roset or any of them don’t produce your stuff, you go to agencies, and you shut up. So the current step-up is not too bad.

If you’re right on schedule, what has worked for you? Were there any turning points for you in the last five years?

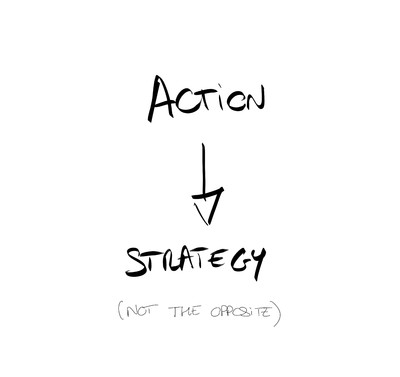

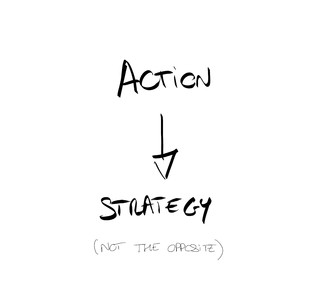

Of course, the first is not to wait. I mean, you know, at a certain point, I won contests as a kid; I won a lot. I came in second place in a Saint-Etienne design contest. I saw how it was going. I thought, okay, I got my designs. For example, at the very beginning, I met someone who worked for Ligne Roset who told me, “If you want, you give me your designs. You’ll see royalties once a year.” And I thought, “Shit, if he’s telling me that, that means there are aspects of the process I won’t be able to control.” And that was not possible: it was non-negotiable. I thought: “We’re going to stop waiting for Galerie Kreo, we’re going to stop waiting for the galleries on Rue de Lille, we’re going to stop waiting for the brands. What we need to do is self-production. I need to do this on my own.” At least I won’t have to wait for anyone.” Producing stuff myself right away cost me €40,000, I believe. I had €20,000 because, as an architect, I made a good living, especially since I made plans for luxury clients. And on the side, my father gave me €20,000. Actually, it was a loan, which I finished paying back not long ago. That was a key factor because you no longer have to ask for permission, which means if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work.

It’s you and your own risks. Nobody’s waiting for you.

Sketch by Joris Poggioli

You must have thought it all out too. Since you don’t delegate, you have to think about your communication, your strategy, your price, what you offer. We saw a designer who told us, “I learned that if I wanted to manage everything on my own, I had to be an entrepreneur, and that meant having to do a lot of things that I didn’t like, that I didn’t have a desire for, and that I wasn’t trained for.”

That’s what it is. 100 per cent.

Are there things you would have done differently or things you would have liked to know?

Oh, a whole damn lot. I wish I had known that communication was the most important thing. You can be very talented, but no matter how talented you are, there are circles you need to be in. I wish I had known… No, maybe it was good not to know.

For example, I remember… I was 26 at the time, and I would go into a meeting with 50-year-old guys and say, “No, no, but actually, it will work! We’re gonna do this, and it’s gonna be crazy!” These guys were doing hotels, and I was asking them to stop their production and do my collection. Like, “You don’t get it; it’s gonna be so crazy! We’re gonna have a show in Paris…” And maybe not knowing allowed me to have that enthusiasm. For example, when I did my first collection, I had all the press in the world. It was crazy. I was doing some prospecting, and in September and I had everything: Wallpaper…

Did you do anything in particular to get that?

I did a press breakfast. I went to a kiosk, I took magazine covers, addresses, and I sent emails, emails, emails… I wrote letters, I wrote to all the people I liked, I wrote and wrote and wrote. For six months, I was in contact with everyone, and for six months, I didn’t make a single sale. Not one, you know? And when you launch something like that, you see your account drain. Doubts started bubbling up, and I don’t know if it was my enthusiasm that saved me at that moment. Because after six months, I didn’t believe deeply in the project. I could have said to myself, “Okay, come on. Let’s do something else.”

GAÉ chair, 2022 Photo: Émilie Krengel

You also said that you’ve seen a lot of change, that ten years ago, you had to go around the galleries, two or three producers… What has changed for someone who is starting today, who is just coming out of school?

Everything has changed. Today, there’s Instagram. Personally, I was against it. We talked about it together. You know it was my wife who created my Instagram? Instagram has made it so that, today, designers are better known than galleries or brands. Who was well-known before? There was Starck… Matali Crasset. You interviewed the guy from Six N. Five, right? Before, that guy could never have existed. There’s a whole generation that could not have existed. I showed up. I thought, “I don’t have a brand, I don’t have anything, I’m gonna self-produce.” But without Instagram or the Internet, how do you sell? I would have sold in Paris in a Parisian microcosm, I would have had one piece a year, and it would never have worked. What worked was that my generation went online. We understood that the Internet was the key, and it opened up the whole world to us. Go straight ahead, without asking anyone anything, without working with Ikea, without…

The same question but with clients: do you also feel that there are things that have changed? That they trust more, that they are more informed, that they are a little better trained?

Yeah. Customers are educated now, they are more informed, they know what they want, and they have far more choices than before. Before, if you were looking for an interior architect, you’d buy an issue of Architectural Digest, take the first three guys, and contact them. Today… with the Internet and social media, you’ve got a plethora.

I imagine you ask yourself this question because you seem to think about your practice a lot: how will you last in the long term?

That’s a good question, and one I ask myself every day. My “why are you doing this?” I do this to move people. I want you, when you look at my pieces, whether you buy one or not, to feel something. If I want to keep moving people, there has to be a sense of sincerity in my work. It has to look like me. It has to be 100 per cent me. To make ten pieces, I design 100. There are many times when you can say, “This is sexy because it’s going well today, and it’s going to work,” but is that really you? Are you gonna defend it? Are you going to carry it for the next three or four years? There was this thing at school I would hear over and over again: “You don’t design for you. You don’t design for you.” But yes, actually, because if you’re not your own first customer, who will be? If I ask you, Simon, to design a watch, you have to like it, you know? You have to want to wear it every day. It has to be the most beautiful watch you’ve ever seen in your life. And my practice, it’s really in my home. My home is a kind of sacrosanct temple where I’m extremely minimal; I’d rather just have a light bulb than have something I didn’t choose. And I’m thinking, would you buy it? Would you have it? So as to be as sincere as possible.

CARLO table, 2022 Photo: Émilie Krengel

You say that one of your main projects is your home. Why is that? You want to make it an image project that you’ll show to say, “This is what I think about interior architecture.”

People think I do luxury design. I fell into that because I wanted to work with the best. And the price followed accordingly. My home shows that there’s another way. I am sure that just through shapes, without some incredible €40,000 lamp, without objects, you can create something interesting. And I’ve tried. I have a small apartment, but it’s a first step in saying, “This is architecture.” Architecture can also be something else. You don’t need to have a Basquiat painting, you don’t need to have Washington lamps, you don’t need to go to the Saint-Ouen flea market and throw down 30,000 euros. You can also have something that functions, that works… through just one shape, formally.

And when can you show it?

It’s almost complete. I think we’ll do a shoot in early January.

Okay. And I suppose you already know who you want to shoot with, how you want to do the art direction…

Alice Mesguich.

She’s very good. She’s got a style. That’s also important to you, I would imagine. You think a lot about the artistic direction of your images, what comes out. Because your last catalogue, Totem, was in 3D.

We design a collection. We see it as much more than pieces. We think, “Why not draw the house where the collection lives?” And 3D is a perfect tool. We did the opposite of a lot of studios. Instead of doing 3D to sell the pieces, we made the pieces and then put them in a 3D world.

And you integrated them into the places where you felt it could help the projection?

What was also interesting was working with Aurore, you know, because we thought… If I show you my first 3D projects, it’s simple CGI.

Aurore, who is an artistic director.

Aurore Lameyre—you know her well—is a stylist. More than an artistic director, I think she’s a stylist. She doesn’t like to be defined like that. She likes… Director of images, that’s the term she likes. She’s got this thing that makes it so that suddenly there’s time in the picture. And that, for me, is super important because the notion of temporality is strong in my work.

It’s interesting what you’re saying, knowing Aurore’s work. How did you come up with this formula around the impresison of time spent on the image?

I don’t know, I never even said it before, I think (laughs).

Well, that’s pretty good then, the fact that it’s brought to life and that it feels real, even if it’s 3D, that we feel the atmosphere. For me, she’s more of an artistic director than a stylist.

Actually, what was hard with Aurore was that, somehow, there were several artistic directors. Except that we designed the houses, we designed the room, and I said to Aurore, “You can take that point of view, but be careful, you can’t see my staircase anymore, and I drew that staircase.” So there was this kind of tension… that she would go get what was important to her and that I would respect my architecture. And at the same time, we sell. We sell objects. The objects need to be highlighted. It was this triptych that was very interesting to work on.

Villa Luce, 2020 Image by photonic

A big project, Youth Editions, I’d like you to talk more about it. How is it structured? Because it’s also very entrepreneurial.

The idea of Youth Editions is simple. All my friends and family say, “You’re annoying. We come to all your shows, we love what you do, and we can’t buy anything.” My answer is usually, “Guys, I don’t have a single piece of my own at home; let’s not kid ourselves!” We have prototypes at the office, broken pieces. At best, we take those. Youth Editions is very simple. I want to be free. And how do you do it—this desire to inspire people, to move people—how do you do it on a larger scale? I think it also comes down to the price. I thought, “Okay, I’ll do it through price, but I’m not gonna do it at just any price.” For example, something that was out of the question—My brother and my dad work in China. I’ve travelled a ton in China. I can tell you about China. I’m not against it at all; there are a lot of very good things being done there—But I didn’t want that. I wanted to work with the people I work with. So this was a huge development for me. We’ve been working on it for three years, saying during workshops, “Are you able, with an incredible magic wand, to dissect the pieces like Ikea and know how we could make them ‘industrialisable’ to have your quality, your eyes on my work, and make things that are as cheap as possible?”

Our ambition is to sell dining tables for €3,800, which is cheaper than things made in China. We only produce in Italy, in workshops. For example, a lamp would be 450 euros, made with ceramic and blown glass. I mean, it’s made in Italy, so we try to… My idea is to think about quality, which is super important, and there’s creative freedom. We’re going to say to all the kids, “Hey guys! If you have cool stuff, come on, let’s make it.”

Sketch by Joris Poggioli

So you’re ready to produce other people’s work, too?

Oh, yeah, totally.

How is that structured? Do you have investors…?

We don’t have any investors. Honestly, when it comes to money today, you can find it. I’ve been lucky. There are a lot of people who’ve approached me to invest. I’ve always refused. As an architect, I work with a lot of property dealers. These are people who could lend us money because we worked hard, and they saw how serious we were. But the idea is to launch a brand for two years and work with retailers we have targeted, who’ve already contacted me, whom I know well but with whom I couldn’t collaborate before because we were working with galleries. We showed these retailers the collection. They are excited, and today we are in the process of calibrating our stock management and so on… But in launching this first collection, we’re showing who we are, what we want. Totally carefree. Like the ’70s, when you didn’t question yourself while you were designing a couch…

Yes, of course.

You know… Beige or whatever. You just want it to let you have fun, for it to be cool. You want to have it in your house. That was the mission of design in the 70s. There was a sense of freedom. Today, I find everything a little standardised. Then again, maybe that’s because of social media or Instagram or whatever, but in reality, it’s possible to do something else.

And how do you do it? I mean, very literally, is it done on pre-order?

No! We’re preparing stock.

You’re preparing stock?

Yeah, we’re going to create some stock, and the idea is to wait and see… And for the next two years, we’ll go through retailers. After two years, we will take over directly through our site, and then it will be structured differently. But the first way of structuring, during the first two years, will be to go to our retailers and say, “Here, what do you think of our collection?” What would you be ready to invest in?” We’re asking straight up for, like, 30,000 bucks, you know? For 30,000 bucks, you get three pieces of each. We have eight pieces, so you get pretty much the whole collection.

So they are completely convinced by the project and its communication since Youth Editions is a producer, a brand, and an editorial line.

It’s a gang. I want us to come together quickly. You know, what brands like Gucci are doing with Alessandro Michele? I find that… I think it’s really, really strong, you know. He came in ten years ago, he came in saying, “You guys, I have a vision for Gucci.”

Yes, but he’s just left.

I was very sad, by the way. But I have a vision, you know, which is to say, “We’re all creative people, come over and let’s do something cool.” And that’s what I want. I want to create a gang. For example, I want Emilie Krengel, the super-talented graphic designer who did all the art direction and graduated from Arts Déco, to be part of the gang.

That’s what I was going to ask… So, she is your graphic designer who is in-house.

Emilie is in-house and works outside too. I don’t want anyone else. But she’s part of the project. I want young designers to come and be part of the project. I’ve got some musician buddies. We put some music up on the site. We’d like to launch a Youth Editions magazine. We’d like the shops to really be something, much like the shops used to be… American Apparel. I have a really branding-oriented vision.

Sketch by Joris Poggioli

Branding is different from design and architecture, of course. So how did you develop that for yourself? You were talking about references in coaching and personal development. Do you read a lot?

Actually, I’m really into podcasts, really into books, and I have a brother who is a fanatic—he’s certified with Google, etc.—he’s crazy about marketing. Since I come from a design background, we battle about this all the time. His view is that marketing runs everything. My vision is that art runs everything. If you take a brand, a company. You create a company, any company, you still wonder how to bring in your vision—in all humility—and in the same way, you think, “Okay, I’m going to arrive at… Kenzo, or Balenciaga, and I’m going to give my creative input.” How can you give creative input to a company? Rather than getting into the whole red ocean, blue ocean thing, which everybody does already, how can you step outside of that? You are going to be laid back, and no one is going to give you problems because your way of communicating, your way of doing things, is going to be different. You’re going to be free; you’re going to be a step ahead of everybody else. And my goal is always to get that head start. Because if you are yourself, guys will run after you, but you’ll always be free. That’s what I try to apply in every phase of Youth Editions. First things first, we’re not gonna have a price war. We’re not big enough, we’re not structured enough, and it’s not our place. The second thing is who we are with and who we want to work with. We want to work with people who will give us that freedom. So we’ll choose. Behind that, who will we compete with? Maxalto, Cassina, B&B, Ligne Roset etc. What is their strength? What is our strength against theirs? It’s our youth. And tomorrow, if we have to release another collection, in two months, we will make it. And despite all this youth, this conviviality, the quality will be crazy good, and our way of speaking will also be interesting. The way we’re going to say, “Okay, now we have arrived.” We draw a lot of inspiration from fashion. My girlfriend was at Acne, now she’s at Balenciaga. I find that they are so many years ahead…

Sketch by Joris Poggioli

In what way are they ahead?

They’re able to come in and say, “Hey, you guys! I’m Supreme. No one knows me. I do a bit of rap, a bit of skateboarding. I exist.” And people wait in line for that. But I find those ways of thinking outside the box a bit, of going to look for something else, the most interesting.

You were talking about strategic references as well. There is your brother, but what about things to read? Are there books you would recommend to people? You mentioned Tony Robbins…

Tony Robbins, to me, is… He’s more than a mentor. He’s… I have his book. I end up reading it—I don’t even know— once a year, more even. It’s super vast actually. Talking about well-being, for example, every morning, without exception, I do sixteen minutes of meditation. And these sixteen minutes of meditation are extremely related to business. If you draw a parallel between your well-being and business, it’s actually the same. You just have the patterns to take and apply. The first thing in meditation is, for three minutes, I say thanks for the cool things that have happened to me. That’s the positive side. During your business day, you always have shit to deal with, I always have shit happening. Being an architect means dealing with shit. There are two ways to take it. I prefer “Okay, that’s shit, but we’ve progressed a bit. We’re moving forward. It’s already better than yesterday.” The second thing in meditation is to think, “Okay, so I’ve done three minutes, I’ll try to put myself in a positive mindset.” Behind that, I try to ask myself to gather the energy within me to go accomplish my goals. So, what are these goals? You set your sights on three goals for one minute and imagine them already being done. They are already finished and you live inside them. This allows you to tell yourself, “I take three things a day, no more, and I try to work on these three things.” In business, it’s the same. You have to be extremely cold. You have to think, “Okay, who are we, where do we want to go, and how do we get there?” And you’re gonna see some really interesting guys… There’s the Harvard Business Review which is cool.

ETTORE library, 2022 Photo: Émilie Krengel

Right now, you are very much into vision, but do you read pragmatic books having to do with coaching for negotiations, for presenting, for pitching?

I think it’s all preview. For example, in negotiation, you have to do the negotiation. There is a very negotiation book that my brother gave me, and its principle is “One of you two will lose. Do you want it to be you or do you want it to be him?” And I don’t entirely agree with that, for example.

Neither do I. I think both have to win.

Exactly. And how can both win? I think both can win by… Well, there are a lot of aspects, but I don’t want people to think I am a manipulator. Every person is different. I did eight years of sophrology and ten years of NLP, and you learn that a person is going to be sensory, cognitive… And by tracking how the person looks at you, the sentences they use, you can quickly pick up on who you are speaking with, so your message gets through to them much faster. It’s not manipulation; it’s just aiming accurately from the outset.

So, pragmatic, prepared, smart, but not cynical?

Yeah, that’s it. And that’s very interesting. Also, being positive is super interesting. Today we’re in a kind of world that royally pisses me off, where you have to show people you’re tired. I don’t know if you feel that way, but today we’re in a generation where you’re tired because you worked a lot, and you have to show that you didn’t sleep a lot because yesterday you were swamped. That way, you’re good. You’re a cool guy. That bothers me because, actually, you can be really positive. You can smile when you get to the meeting. It’s going to go well, and what we’re going to do together is going to be really cool. And for example, in a negotiation, I prefer to arrive, you know, with a mindset, I come with…

We’ll find a solution?

We’ll find a solution. After two hours, you and I will be happy and satisfied. We’re not at war. We aren’t samurais.

Especially in the logic of conflict: if you win, whoever loses will eventually realise it, and that will negatively affect the quality of the subsequent relationship.

Exactly.

You talk about being surrounded. How did you construct that? How do you choose the people you work with?

We want to get to 20 people. About 20 or 25 people. And if you want to get there, you can’t skip the steps. Always that notion of the staircase. And your base has to be solid; you have to add people who fit into the hive that has been built around me. We have brought in interns. These interns often become freelancers for us, and we usually recruit from that pool. So we started with three… Or two people. Those two people, we had a very intimate, very exclusive relationship because we shared an office. We figured we’d start our super simple, and we would tell each other if we were going to add someone because that energy shouldn’t be wasted. That’s why we started with the internship, with freelancers. Once we have the person pegged, we take them in. That’s for the human side. For the professional side, we always ask ourselves, “How can we go further?” There are guys who are better than me everywhere. I’m just the conductor of the orchestra, you know? I am the one giving creative input. But how can I surround myself with people who know how to do certain things better, who are going to be better than me at certain things? Aurore is better than me. Émilie is better than me. I have a person at the office named Jeanne, who has done several hotels. She joined because she had the ability to do hotels. Each person comes bearing their own expertise. There was something we stopped doing because it was really annoying, but every Monday morning, I asked the team to arrive with something cool they had seen during the week. Anyway, I want them to feed the agency. It’s not the agency that feeds you; I’m going to fade one day. I’m going to become annoying, I’m going to repeat myself, and it’s going to be painful. And then have them talk about what they were going to do that week, if they needed help or not, so that everyone knows what we’re working on.

And what about skills outside the studio? For example, have you worked with PR?

Yes.

How do you choose that then? Was that in your vision? Did you ever think at any point that it wasn’t something you wanted to manage? That it wasn’t a job you could have in-house? In my opinion, maybe when you get to 20-25, you’ll have a director of communication?

I’ll get back to your question. I think imitation is something that works well, examples that work and are interesting. For example, companies like Hermès or Molteni. They both do it the same way. They outsource a lot to remain free. And for example, 3D is something that I outsource a lot because 3D is a field that evolves all the time. You need new talent all the time. Still, with our need in 3D, we could have someone at the agency do it because we have enough work to do it. But I prefer to outsource. We have an agent who works for us almost permanently, as if on a long-term contract, for the whole year after the pieces are produced. It’s something we prefer to outsource because one day I’m going to need a glassmaker, and one day I’m going to need this or that, and if you have someone in-house, that person is going to be hyper-trained, for example, on wood. But then if you do a marble workshop, they’re going to be quickly lost. The same goes for PR. You can start with a Parisian firm, for example, but once you’ve mastered Paris, you think “Actually, we don’t sell anything in London. We don’t work there.” So then you get a London office, and then you get an office in New York, in Dubai… It’s something that is cool to outsource. Every three months, you can reorient this; we work with a company called DLX. Our ambition is to open a gallery in the United States. And he has an office in the States, so he was the perfect guy. Originally, he was actually a client who bought a couch from me. So we share an affinity both in terms of aesthetics and people. We got pretty close and figured, why not do something together? Knowing he had the ability to manage much more than PR. I wanted someone who had a vision. He’s a guy who works with Lego, who works outside of fashion and design. Because it was precisely that vision that interested me. And he’s someone who can go to the States with you and tell you, “Okay, we can be here too.”

ARI bench, 2019 Photo: Gabin Roux

So, right now, you have an international strategy?

We’re trying. It’s very hard. We’re just starting and it takes a lot of time… For example, one of the dealers I work with in Australia—and Australia is a gigantic market, really, people don’t suspect it, but it’s crazy—tells me I have to go there at least three times a year. So at least three trips a year, maybe for three weeks, are already booked in Australia. The most recent podcast I was listening to, which was amazing, was about Alain Ducasse. He says, “My life for six months is going to be touring all my restaurants around the world,” which does not surprise me at all. Because your presence is necessary, and you need to transmit that energy…

You partially answered it, and it’s a small detail, but it’s always interesting: how do you manage your presentations? Your first pitch… With a brand. You don’t design too much for other brands, for example.

Yes, for American brands.

Oh yes! You talked about it, sorry.

No problem. They happen to be so huge that today we think, “Either the opportunity is enormous, or if it’s small, we don’t want it. Because important brands give us a lot of work and need millions of pieces, so they take us a lot of time, and that’s enough as is.

So, how do you handle that presentation?

I think there’s a lot that goes unsaid. By some kind of…

Mehrabian’s rules.

Yeah, that’s it. Everything that’s happening outside of what you say. When you talk to someone, for every word you say, the person will start to build a picture in their head, and every word will be a colour. Imagine you’re a painter: it’s gonna be red or blue, it doesn’t matter. The idea is to think, “How do I make it so that, at the end of my speech, the image in the head of that person is something I created?” And so the words you’re going to use are going to be different depending on the people you have in front of you and how many there are. For example, for Restoration Hardware, I had to present my collection to 450 people in English. And so the task was to say, okay, I will get to that image—

Marcello Bold desk, 2019 Photo: Gabin Roux / Serdar Demir

Marcello Bold desk, 2019 Photo: Gabin Roux / Serdar Demir

How were there 450 people?

Because they have thousands of shops around the world. And so it was all the shop people who had to sell my collection.

You were pitching so they could pitch well and also could train their sales staff. Their sales force?

It was very interesting to wonder at what moment I could bring energy to a crowd of 450 people who were far away, with the connection working badly, not the ideal context to make them come out of it with the single desire to buy my pieces. So you work a ton on your presentation ahead of time, visualising what you’re going to say and the final image that you want to leave in people’s heads. It could be, for example, by showing an image or not, telling them about a key element before they say they like it or not, and reassuring them about a common reference. The idea is to do everything to achieve that goal, for the person to have that feeling, that smell. I had an architecture professor who always said, “Never forget the smell you are selling.” Say you are designing a chair: if it has a name, what is it? What is its smell? Do you want it to smell old, or do you want it to smell young? And if you can build that image in your client’s head, you win. Whether they’re going to like it or not is another question. But, regardless, you’ve got your message across.

Do you also have strategic references, apart from books, designers, and architects? Any references elsewhere? You mentioned fashion brands, for example. Do you have any other strategic references to share?

Yeah, I have plenty. I’m convinced that it comes through art. If I had to summarise my mindset, I would say it is to take a brand, think a lot about the things that have never been done, and implement them. Jacquemus shows that. I mean, a lot of people show it. You go into the brand and you reason like an artist. For example, today’s fashion is constructivism. How are we going to get to minimalism or modernism? There are solutions. We just have to find the substance of your message and who will make it real. I love cases like Kodak. I think about Kodak all the time. Those guys were chilling! They dominated the world. And then, the camera was over. NFTs really reminded me of that. I thought, “Wait, are we experiencing the end of something here? Is this not a sea change? Or is it too big? Is it not big enough?” For example, on sustainability: many people talk about it, but what is it? I’ll take you with me to a workshop in Portugal that is 300 years old, and the guy there—when his brass doesn’t sell—takes it, puts it in the oven, and remakes a piece. He has no website, and the guarantees are zero. But he lives on sustainability.

Another thing, my brother showed me a guy who talked about second and third sources of income. That’s an extremely interesting subject. For example, I sell design, but how do I get a second and third source of income from my main business? When you manage to do this, it’s of great interest to the studio or workshop. I never wanted to be caught with one client or one subject. I find that too dangerous.

Rick Chair, 2020 Photo: Mathijs Labadie

That’s a question I wanted to ask you: do you recommend having a side job at the beginning of your career? When you are a young designer who is starting out, there is a difference between a side job and a second source of income because that is the case in the current market. There are plenty of young designers whose vision is to produce objects or to have objects published and maybe live off that but who are forced to go through other things. They do set design and CGI. They do scenography more than interior architecture. What do you think about that, given that you self-produced very quickly?

I’ve always been very cold on this. We have to eat. So we have to stop with the delusions. I hate studios that say “Oh no, no, we’re going to do the best door handle in the world; otherwise, we won’t work.” But who’s going to pay your rent? My parents wouldn’t give me money for my rent. And my collection, I was the one who paid for it. I mean, everything you see today is self-financed. There’s no money from mum and dad. But how? Because we work, we have like 20 architecture projects throughout the year. And you don’t know that.

And you’re gonna show two or three, the ones that represent you best.

I work for the CNFPT, which is the office that trains civil servants in France. It’s a platform. Creatively, it’s not super interesting, but it is what it is: money that comes into the workshop and that lets us create prototypes, spend money, go work with people, create the Totem catalogue, which is a total investment for us, which we don’t necessarily see a return on. I never think about money in that sense. I think money is a medium. What do you want to do? You want to make a collection? Okay, to make the collection, you need €20,000. For those €20,000, you’re going to do odd jobs on the side to get it. So you get that money, but not for long; you put it back in your collection. When it comes to money, you have to be very careful. I see it with lots of young people who come into the office. They think, “Okay, to make my collection, I’ll make CGI,” and they start doing CGI. It’s extremely well-paid today. If guys are even a little talented, they think, “It’s cool to make three, four, five thousand euros a month.” They get used to it, and then it’s all fucked up because…

Because it doesn’t develop their corpus.

Exactly! You are no longer reflecting and saying, “I have to design my collection.” You think, “I’m making money; that’s cool!” And as soon as things get comfortable… There’s this guy I like— Well… I like him, and I don’t like him. It’s Anthony Bourbon, the founder of feed. He is so crazy. He’s a millionaire. He has an apartment. He lives in 42 square meters and has a sofa bed. Everything is limited; things can’t get comfortable. You have to be hungry. In the morning, you need to always have that desire to do things. Big things. I think your desire can arrive in other ways, but, in any case, these young people can’t forget their goal; why did they start this in the first place?

Sketch by Joris Poggioli

And one has to think about their communication, their image, enhance it. But only with the projects we chose in advance. Obviously, there are some projects you will never communicate about.

For example, we hesitated over something a long time ago. It was a big doubt at the agency. Zadig & Voltaire were reviewing all their global communication, and they wanted to go upscale. They want to remove themselves from the Sentier neighbourhood. They invested in Château Voltaire to have a sort of Château Marmont in Paris, and two years ago, they created the Voltaire Prize, which they want to have become like the Goncourt Prize. They come to us, and they say, “Here, actually, we would like these objects. Design them for us.” The exercise was really great: design a prize. It was super enjoyable for me, creatively speaking, and for the studio… But you have the image behind it. I say, “What am I doing?” Well, we thought, “We’ll do it, but we won’t have to communicate about it either.” Few people saw it. It went unnoticed, but for us, creatively, it was super interesting to do it. We had carte blanche.

You mentioned homogenisation in the design market. That seems real to us. Do you really think this homogenisation is widespread? Or is there hope? How do you see the design market?

So, I see it two ways. I see 80% as boring, really boring, and 20% as really cool. I think it has really become a confrontation. There’s not much middle ground anymore. For example, Instagram. I read a very interesting article saying Instagram is no longer chronological; it’s now organised by image style. I mean, if tomorrow you put a picture on Instagram, you make it a bit beige, a bit cool, with a bit of sand, etc… You’ll be at the top of the list. You’ll get seen and get likes. What does that say? It says that, for example, if a small account that puts little, super niche pictures, the kind of super cool stuff that I love looking at and that wow me every time, the kind that makes me think, “Damn, these guys went looking for furniture… 1929, I’ve never seen this in my life. Norwegian, so cool!” Well, they will never be in my feed, and unless I check their page, I will definitely never see it because it doesn’t fit the criteria. And so there’s this tendency to say, “Okay, we’re going to create a big wave.” And today, I feel like the young creatives want to be on this wave so much that they jump on it, even though they can do so much better. And then, you’ve 20% of the guys—There’s a guy, I need to give you his page. I think it’s called Design Only or Futur Design—He takes mopeds, and he does them in 3D in a way that’s kind of like they’re coming from the future. He has a sense of freedom that is exceptional. And it’s kind of the same with fashion. What Bottega Veneta does today, for example, you go to their shop and fuck, it feels good. You think “Wow, damn!” They’re taking risks. I feel there are brands that manage to take risks, and it’s great to see. On the other hand, I hate Netflix, for example. Why? Because they’re feeding into something. It’s a feedback loop: “We are like this because it actually corresponds to 80% of the population, and so we will feed that 80% of the population.”

So, how do you keep an eye on all of that?

Well, I’m lucky to have always had a bit of an appetite for that. But for example, I always force myself to go towards the unknown, even in food or in music. And also a lot in the library. The relationship with books, the temporality of the book. To have one image after another, that’s what you said at the beginning of the interview. I take the team to the library, and I say, “Now you’re going to take 5 books that you don’t know,” and I take only that, the names I don’t know. I arrive. I open. I look. And then the interesting thing is to ask, “Why did I like it? Why didn’t I like it? Why did you like this?” Really, you ask yourself the question, and at least you get something out of it.

Rose sofa, 2020 Photo: Émilie Krengel

That’s a step that Clementine from Tools magazine does. She goes to the library. She even takes her scanner. And she says, “There are tons of stunning libraries, even in Paris, and you always discover things you haven’t seen elsewhere.”

But you see, right now, for example, what I’m doing with the hotel, it’s cool, and I’m happy with what I’m doing. But it’s also part of a trend.

When you do design, you’re in direct competition with vintage. How do you view that? Is that a threat?

Not at all.

Do you have vintage things at home?

Yes, a little, but not much (laughing). Something that was really bothering me was the copycats. You could know just a tiny bit about design, you could go copy a model from ‘68, one that was not very well known in Italy, and you would take it and produce it. For example, there is a lifestyle site that produces things as well: all their pieces of furniture are copies. If I cite the references, you would think it wasn’t possible; they’re the same. But they don’t get attacked for that. How is that possible?

Are you protected in terms of intellectual property? Because I feel like it’s super important for designers right now.

I think it’s total bullshit. I’m in several disputes right now. I’ve got ten open cases. Let’s say I have someone who’s copying me. We send letters, but… what good does that do? People copy me freely, the same things. You send a letter. What do you do after that? Only if a big brand copies, it is worth it.

Of course.

But if it’s someone my age, we won’t get money out of it, so we’re not going to spend money just so he removes the pieces. Honestly, it’s a real nuisance. Right now, we have ten cases: it’s hell! It costs a ton, and it’s all for very little. I’m on the verge of saying let’s just let it go.

Are there any other developments that you are observing in your profession? You were talking about young designers who maybe do too much CGI and begin to fool themselves. Are there other developments, positive or negative?

The major evolution coming, I think, and I would be the first to invest in it, is 3D printing. It’s amazing, we already use it a lot in the office. I think everyone will have 3D printing at home in the future. You’ll buy your files and make your furniture with them. We’re looking to buy a 3D machine for printing armchairs made of recycled plastic. That’s your production tool. It’s total freedom. You launch, you do the 3D, you print, you sell. What is more painful is that I feel that design is going through what fashion went through in the 1930s. There are lots of studios popping up: it’s the new El Dorado. And you see a lot of people coming onto the market who don’t do it very well, which kind of hurts our practice, I think.

When you talk about El Dorado, it’s going to seem surprising to our readers because among them are some good, designers who are struggling. In what way do you see things moving a lot in the market? Tons of young brands, tons of young projects…? It is still very difficult to produce on a large scale at the moment, without investors, without…

No, but, for example, what Zara Home does.

Sketch by Joris Poggioli

That is on a large scale.

What H&M Home does, you know. They’re going to do travertine stuff in China, in India. They’ll come back and put travertine on the table. What does it say about travertine? “Well, I went to H&M. I bought my bowl for €24. And Joris, he doesn’t make bowls; he makes stools, and they sell for €4,500.” Why? Well, there is the question of the quality of the travertine. There are twelve degrees of quality with travertine. We are in the twelfth. There is the purest travertine, close to Rome, which is not made industrially in India. And also, something that annoys me incredibly—this is my big rant—is that you also buy a design that is by somebody specific. Except that, a saucer, let’s say, that’s a design that people aren’t willing to pay for today. People buy brands. They buy names and signatures but not designs. So that creates a blurry line that is pretty difficult to manage, you know.

On the other hand, there are brands like Muji that erase the notion of the author by making the designers anonymous. This is very interesting for their editorial line, but also because designers know what silverware is by Jasper Morisson.

Personally, I think that is cool.

It elevates the overall style somewhat only if we know that Muji works with good designers.

I think it’s a super—you know, with Muji, it would be really great. The problem is all these brands that are coming out that are copying a bit. Or are “strongly inspired,” we’ll say. Shit, there are enough designers for everyone. Work with someone. Design the thing.

Another potential threat or not: artificial intelligence?

No.

For photographers and 3D artists, it is becoming a threat. We feel there will always be a need for artistic directors. People who think about the idea of the image. What about design?

I’m not afraid of that at all. If you’re afraid of that, it’s because what you do is not professional enough. It doesn’t go deep enough. You need to look at yourself first. There’s a really cool site, IAO, where you can create images. I typed, “painting future furniture.” But their future is Stanley Kubrick.

Constantin side table, 2019 Photo: Giulia Fassina

We just have a few trivial questions to finish with. What if you had to do another job at another time in history?

I’ve been thinking about this for two days, and I can’t figure it out. What would you have done?

Aha! (laughing) I’ll try. There is one author I love, Henri Laborit, and his small, general audience book, Éloge de la fuite (In Praise of Flight). So I would have loved being a neurobiologist at first for the initial research, but I wouldn’t have had the intellectual capacity for it, I think. I really like when Laborit explains that he invented anxiolytic drugs. He is modest; he says, “If I hadn’t invented it and nobody had invented it either, more than half the population would suffer from neurosis. We can no longer go on at this pace.”

I liked what Teruhiro Yanagihara told you: He would have liked to be a fighter in the samurai days.

Your rugby side is coming out.

Yeah, I like that. I don’t know, but coach, yes, I would have loved to. I hang out with too many creative people who are brilliant and who aren’t able to speak well about what they do, to go look inside themselves for that light to carry them and carry others towards something. So helping those people is something that motivates me. For example, with Youth, what we earn, we want it to be fruitful. Basically, what we earn, we want to donate it directly, pay for the education of a disadvantaged student and pay for 50 design courses. The idea is to make a school. So coach. Yeah, coach.

We talked about books. Are there artists who have recently changed the way you see your work?

Paolo Sorrentino, the director of La grande bellezza (the Great Beauty). Because I was debating for a long time whether or not to make movies. I was talking about time with Aurore. I find that these films touch on a certain timelessness, and this notion of temporality in my work obsesses me: what trace you want to leave and what message you will give. And I feel like it touches on that notion… By looking at cities like Rome. Or relationships, or Naples. This notion of temporality is just talking about your time with your own eyes. If you talk about it well, it will stay for a long time. Otherwise, I really like athletes. There’s an MMA guy named Khabib Nurmagomedov from the mountains of Dagestan who came, did the biggest competitions in the world, won 30 fights in a row, and left. And they asked him, “What is it that made you unbeatable in the cage?” and he said something that I find very interesting: “When I decided to do this, I decided to go into a cage and fight. So I was good in that cage. I could have stayed there all night if I wanted to, you know. While the guy across from me came to fight me and leave. I had actually decided that I was there, I was staying, that it was like my home, that I could stay there all night. I decided to be there.” I think from the moment you’ve made up your mind, you’re gonna do it, as long as it’s decided, you wanted it, and there’s no reason why it shouldn’t work.

The final question is, do you have any advice for those in the creative professions, not necessarily in design or architecture, but just those who are starting a career as a freelancer?

I think that you shouldn’t expect anything from anyone and that—and this is something I was obsessed with—nothing is impossible. I’m very hard on people who say, “I’ve had bad luck in life. I come from a disadvantaged family.” That doesn’t move me at all. If you have a dream that eats you to the point that it wakes you up at night, whoever you are, you will make it. I’m from Grenoble, at 19, and I didn’t talk about this, but I’m in business school and a professional Rugby player and one day, I blow a fuse. I quit my business school. I get up in class, and I leave. And my dad says, “Well, if you drop out of school, you pay the rent, you know.” And so I worked for a year in the press doing, I don’t really know what, not knowing what I was going to do because I was a rugby player on the side. And now I wanted to do a personality test. It’s been a very serious test for 40 years now, with 40 questions.

Myers-Briggs?

Yes, I think so. I’d never read a book before. The only thing I listened to on the radio was Skyrock. I was a guy from Grenoble who played rugby. I didn’t know about museums. And there you go. And I’m 19. The girl arrives after the analysis, and she tells me, “It’s simple. You are 100% creative.” And I tell her, “but my father is a locksmith in Grenoble. Like, it’s not even an option. I don’t even know what creative means.” You know, interior architect, I didn’t know what that was. I knew architects and construction sites because I worked a lot on the sites, but that’s all. And from that moment, if you like, my life started over again. And so I’m very sure that no matter who you are, way out in the countryside, you can outdo yourself in Paris and break the game if you really want to.