Could you please introduce yourselves?

My name is My Kim Bui, and together with Faris Kassim, we co-founded OKOK Services.

FK

I’m Faris, also the co-founder of OKOK Services.

Messages with OKOK

How would you describe OKOK’s current activities?

We are a small independent studio, it’s just the two of us. At the moment, we are mostly working on digital projects for clients across different fields like fashion, music, culture, and art. We also collaborate with fellow creatives and friends who require creative digital solutions.

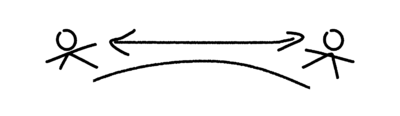

The founders of OKOK Services

We’re in early April 2025, what’s your current state of mind?

My mindset is quite different compared to previous years. I used to be anxious and stressed about everything. Even when I was hanging out with friends or family, I’d be thinking about all the things I had to do, this endless to-do list. I was constantly worried about the future. This year, I’m trying to be more present, more mindful. I’m making an effort to really listen during conversations and focus on what’s happening now, instead of stressing about what’s next.

FK

For the past decade, I was living abroad, and I just came back to Singapore late last year. I’m trying to spend more time with my family and old friends I grew up with. Outside of work, it’s been a tough 12 months. So I’m also focusing on improving my health, physically and also spiritually. Hopefully, this year will be a refreshing one for both of us.

OKOK Services’ offices

Could you tell us about your setup in Amsterdam and Singapore? How did it all happen?

We met almost 10 years ago now. I did an internship in Singapore while I was studying in Belgium. I ended up working at Bravo, the same branding studio as Faris. To be honest, we didn’t really work together much at the time, but we stayed friends and kept texting each other visual things or cool things we had seen. Our first proper collab began when I shared a particular idea with Faris, and we thought, “Shall we just do this?” We then asked one of our friends, a photographer named Amos, if we could design his portfolio based on this idea we had. And that’s how it started. We made one thing, then a second, then a third and suddenly we had a studio.

FK

As My Kim said, that was around 2013 or 2014. I was working as an interactive designer and developer, and My Kim was working on branding. Bravo was a small studio of about six or seven people. I’m usually quite quiet, so I didn’t talk much. My Kim reached out to me, randomly sending a text one day. I think she was also looking for friends during her time in Singapore. That’s how we got to know each other. After she left, we kept in touch intermittently. A few years later, when I was living in Korea, her sister was studying there, and My Kim came to visit. We hung out, and that’s when the ‘Amos Yong’ project came about, in September 2019. We’re now still working from different cities. My Kim is mainly based in Amsterdam, and I’m currently in Singapore. I’ll be moving to Bangkok in a couple of weeks. So we’re still looking to keep this dynamic going.

Work by OKOK

What got you into graphic design and specifically digital work when you were younger?

When I was around 12 or 13, I was watching a lot of anime, like Dragon Ball Z. I didn’t really have anyone around me to talk about them with in real life, so I started going on anime forums. Back then you had to have these custom-designed signature banners for your profile. On that forum, someone shared a bootleg version of Photoshop, so I downloaded it and started making those banners myself. But honestly, at that age, I had no concept of what graphic design actually was. I didn’t even realize I was “designing”, I was just putting things together. Then people on the forum started requesting banners from me. That’s really how I got into Photoshop. But I never thought of having a creative career. I didn’t even know such a path existed. Still, that’s how I got interested in design—I started looking at blogs, Tumblr was big at the time. It all kind of developed naturally. I didn’t come from a creative family—my parents and siblings weren’t in creative fields. It was something I just discovered and got into on my own.

FK

It’s something I really only understood in hindsight. When you’re growing up, you don’t always realize how certain things shape you. I think my first real fascination with how things are designed and experienced came when I was five or six. My dad bought a Sega Genesis or Mega Drive, this was probably in ’94 or ’95. When you play games back to back, you start to notice a pattern: how every game has an intro screen, a publisher logo, menu music, pause screens. I found those details super intriguing. TV was all live-action, but games were made up of moving flat graphics. I didn’t know it at the time, but that was sprite animation, and I was fascinated by how it all worked. Later, in my early teens, my older sister had to use Photoshop for a high school project so we had it installed on the home desktop computer. I started playing around with it, particularly using the clone tool to remove sponsor logos from football jersey, stuff like that. That was my first hands-on experience with Photoshop. Then came DeviantArt, downloading brush packs, experimenting. I wasn’t really creating original work, just putting things together and trying to imitate stuff I saw around me. In middle school, everyone had personal blogs, and customizing your blog layout was a big deal. I’d copy existing templates, change colors, swap images—that kind of thing. Looking back, I think all of that was kind of a precursor to what I do now: mixing design with coding.

When did you decide to actually found OKOK? What was your intuition behind it?

Like we said earlier, it kind of happened by accident. We started with one portfolio project, shared it on Instagram, and then someone—our first client, from Japan—reached out. We had no idea how to handle invoicing or make proper client presentations. At the time, we both had full-time jobs, so this was something we did on the side, after work. But then more people started noticing, more clients reached out. Eventually, we had to form a proper company. It all just happened naturally—we needed a name, and that’s how “Services” came about.

FK

Even before we officially started, I always had this vision that maybe, one day, I’d start my own practice. Working in the industry I’d look up to people more senior and think, “Okay, maybe 10 years from now, I’ll have my own studio.” I didn’t know how or when that would happen or whether I’d do it alone or with someone else. So when we started, we still had full-time jobs, so we were just doing fun projects for friends, with zero pressure, no financial obligations, no need to figure out accounting. Then it started snowballing: more projects, more visibility. It became something that could actually be viable. I think that slower, organic start helped us ease into building what’s now an independent studio.

Once you realized it was taking off and becoming a real studio, did you have any creative references in mind? Any studios or individuals you looked up to?

I never had any formal design training. I started working straight after high school, so naturally, I was always learning by observing those around me, kind of reverse engineering their processes. I looked up to the people I worked under early in my career, more than specific agencies. My first real studio experience was a 3-month stint with Asylum, a studio in Singapore, led by Chris Lee. He’s one of the OGs in the Singapore independent design scene, having started the outfit back in the ’90s. Being in that environment taught me a lot of things I never really understood before. For example, I used to think a design studio was just “The client gives you a brief, you make something, and send it back.” But then you realize there’s a whole infrastructure: client servicing, accounts, internal workflows. Later, when both My Kim and I were at Bravo, it gave us a more relevant view of how we wanted to work. It was a very small studio, so you’d be designing and managing clients at the same time. That hands-on, all-in approach helped shape how we’ve structured OKOK today. Being around creative people has always influenced me personally deeply.

MKB

I’ve always followed a lot of studios and individuals I admire. Back in the day, I really liked Tristan Bagot’s work. But more than following specific studios, I was always drawn to individual creatives working within studios. That mindset kind of shaped my career path. I’d admire someone’s work, find out where they worked, and then try to work there too. For example, I joined Bravo because I really liked Preston Tham’s work (he now runs Design Everywhere), and later I went to Wonderland because I admired Jack Bach, a creative developer there. That’s how I’ve navigated my creative journey—by following people, not necessarily brands or agencies. And honestly, that mindset extended into how OKOK came to be. It wasn’t a strategic, long-term plan. We just started taking on work that interested us, clients started reaching out, and it all fell into place from there.

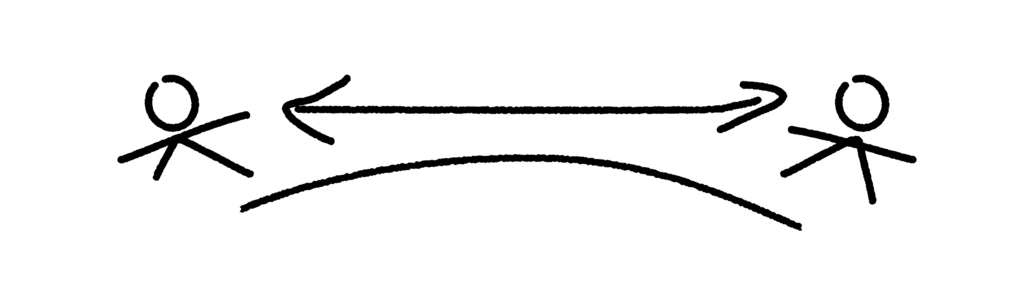

How do you work together creatively?

We’ve figured it out over time. Initially, we thought we’d operate like a typical studio, working side by side, actively collaborating in real-time. But with the time difference, we had to adapt. These days, our workflow is as much iterative as it is collaborative. I usually start the day earlier, depending on where we are in a project. At the beginning of a project, we align on creative directions. Then I get started, and a few hours later, My Kim begins her day and builds on what I’ve done. We overlap for a few hours, which allows for real-time collaboration. Our skill sets are very complementary, we both design and develop, so the handoff process works well. This asynchronous rhythm has actually turned out to be pretty ideal for us.

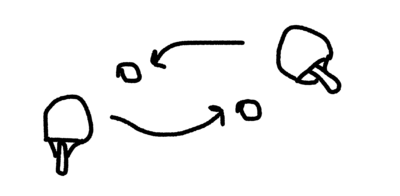

Sketch by My Kim Bui

What’s the current time difference between Amsterdam and Singapore?

It’s about six or seven hours depending on the season. It used to be even more when My Kim was in Seoul—around eight or nine hours. She tends to start her day early while I’ve slowly shifted my routine to start my days a bit later. We used to only have two or three hours of crossover so we’ve created more overlap.

Design for {ADIDAS : PRADA, RE-SOURCE} with R.N.A

And beyond the time zone, are there other creative challenges? For example, will it always just be the two of you working on all projects?

The biggest challenge is at the start of a project, agreeing on a consistent direction. That’s always the most delicate part. Once we’re aligned, the rest flows more easily. That said, we haven’t had many issues because we often have a very similar vision. But of course, there are moments where we both feel strongly about our own opinions. When that happens, combined with the time lag, it can be tricky. We have to make our points separately, then come back together later to find a middle ground.

MKB

The time difference is helpful in a way. It gives me more time to reflect. If he designs something, I have almost a full day to think about it before I iterate or build on it. And then the same goes for him the next day. This staggered process actually gives our ideas more room to breathe.

Design for {ADIDAS : PRADA, RE-SOURCE} with R.N.A

My Kim, you mentioned some models you had in mind, people you could see working and wanted to work with. Do you also have strategic references? Any studios you think have developed in a particularly smart or thoughtful way?

I’ve always been impressed by the work of Two Much Studio. They are also a team of two, similar to us, and their output is consistently strong. But it’s hard to know what their actual strategy is, because for us, everything happened very organically, it’s really just been about creating work we’re proud of, and that naturally attracted clients to us. That said, more recently, we’ve been making an effort to reach out to clients we admire or where we see an opportunity to bring something valuable to the table.

FK

The way we started was very much a side project. We could be quite selective about who we worked with. It wasn’t really about running a studio in the traditional sense, it was more like: “This looks fun, we have time, let’s do it.” But in the last couple of years, when we made the shift to doing this full-time, we’ve had to be more intentional. We’re learning to think more like a business: how to grow, how to manage our time and workload better, how to bring in new clients and keep things sustainable. Reading interviews on Developments, for instance, has been helpful. It gives insights into how other studios operate, things we wouldn’t necessarily know unless we had those conversations ourselves. We’re still learning, day by day, the studio is still in a relatively early phase.

Do you have a clear idea of what you’d like to focus on or improve in the coming months or years?

I think we each have our own personal vision of how we want the studio to evolve, but there are definitely areas where we align. We try to keep an open dialogue about it, what kind of work we want to do, what kind of clients we want, how we want to grow. At the end of each year, we usually sit down together in person since we only meet maybe once or twice a year, to reflect and set goals for the next six to twelve months. We even share our personal plans, like if one of us wants to start a side project or business. That openness really helps us stay aligned and support each other.

Design of the ‘1000 ORIGINALS STORIES’ website for Adidas Originals, in close collaboration with R.N.A

Where do you usually meet when you meet in person?

Anywhere, really! Last year, for example, he came to Amsterdam. This year, we met in Hong Kong. So sometimes it’s just like, “Hey, are you around Asia?” and we make it work. Those in-person meetings are really valuable to align and talk strategy.

FK

It’s usually pretty spontaneous—nothing we really plan far in advance. I head to Europe every couple of years, and My Kim’s often in Asia, so we just take the chance to meet whenever our paths cross. The opportunities kind of present themselves naturally.

Lookbook design for the Adidas Originals × Human Race Premium Basics SS22 collection by Pharrell

And do you have an ideal or rough plan for the next couple of years?

Personally, I just want to stay open to whatever opportunities come our way. I know it sounds like we don’t have a strategy, but it is how we started. When Adidas first approached us, we were intimidated. We didn’t think we had the skills. But we said yes, and it turned out to be some of our best works. And they kept coming back to us. That openness is something I want to maintain. I don’t want us to get boxed into a specific industry or way of working.

FK

A lot of our past work has been execution-focused, but we’re starting to take on more conceptual roles as well. We’re interested in expanding beyond digital, into spatial design, campaigns, print work. Both of us come from backgrounds that include those disciplines, so it feels like a natural direction. Even though most of our work is digital now, it’d be great to offer more holistic creative solutions moving forward. For example with our many collaborations with Adidas, we’ve often handled one specific part of a larger campaign. But we see how all the pieces fit together, and we’d love the chance to shape a project from the very beginning—setting the creative direction, not just executing on a piece of it. Hopefully we’ll have more of those opportunities in the next year or so.

Are you ever involved in pitch competitions?

No, we strongly object against it. In Singapore - where I’m from, unfortunately there is still this really unhealthy practice – especially among government agencies and institutions like museums – of asking for free pitches. We’ve always been against it, not just because we’re a small team and don’t have the bandwidth, but because it’s simply unethical. Asking for unpaid work just shouldn’t be happening in this day and age. That said, I do know a number of friends who run studios in Singapore who still participate in them because unfortunately, that’s often how you get access to these government projects, which are better funded if you win them. It’s a tough situation, and I hope it changes. We’ve always rejected the idea that you need to give away your ideas for free, regardless of the project size. Some agencies like Porto Rocha have also taken a stand with their “No Free Pitches” initiative, which is great to see. There’s a growing awareness, globally, but Singapore’s a bit behind. Hopefully that shifts soon.

You’ve mentioned that you try to reach out to new brands—how do you approach that?

Mostly remote. We follow a lot of creatives and studios online. When we see an opportunity, like someone posting that they are looking for creatives, we will just send a cold email saying we’re available and interested. Sometimes that leads to a conversation, sometimes not, but it’s always useful as it helps us build connections, and it expands our network.

FK

Even though I’m from Singapore, most of my years in the industry were spent abroad. So when I moved back last year, I actually had to do some groundwork, reaching out to local studios, talking to friends, trying to find out who’s doing what locally. Also the thing is, OKOK has always been a bit ambiguous as a studio. People might know the work we do but don’t necessarily know the people behind it or the fact that I’m from Singapore. I’ve realized that being more clear about who we are as individual personalities rather than the studio also helps build local connections.

MKB

We travel a lot, so whenever I’m in a new country, I’ll just reach out on Instagram and ask if someone’s free for a coffee. Sometimes it leads to work, sometimes it just leads to friendships—but both are valuable.

FK

My Kim has definitely been more proactive about that. I’m a bit on the quieter side and not the best at reaching out and networking. But when I travel, I try to meet people too. And at this point from the few years of doing this, we’ve also built up a stable of trusted collaborators that we can rely on. So when we take on a project that needs a specific skill set, we already have people in mind who we can reach out to. It’s been really valuable for that reason too and not just acquiring new leads or clients.

Design and development of Starch Haus’ new website

How do you handle your communication and public presence?

We have a website, Instagram, X, and an Arena account. But honestly, we’re not great at social media, even though I consume a lot of it. When we finish a project, it often takes months before the client approves it for release. Once it’s approved, we usually post it on our Arena channel (Works by OKOK). But since it’s just the two of us, we’re usually so busy with projects that we don’t take the time to make proper posts, even after things are released.

FK

This year we’ve made a bit more of a conscious effort to be more proactive about communication. So you might suddenly see work from two or three years ago being posted. Some of our best projects are under NDA jail and might not ever see the light of day unfortunately.

Design and development of Starch Haus’ new website

Also, you’re a very digital creative studio, but there aren’t any photos of you online. That seems like a deliberate choice.

It was. When we started the studio, we were both working full-time jobs. And technically, we weren’t allowed to freelance on the side. So we chose to stay anonymous.

FK

We later realized that this ambiguity actually worked in our favor. It gave people space to project their own assumptions. Some people thought we were a 30-person studio. Others assumed it was just one person. Because we’re based in two cities, it creates this sense of scale or flexibility, depending on what someone is looking for. That ambiguity sometimes helps open doors, clients see what they want to see before they know who we really are. But that said, i think in the age of social media, having a very relatable personality and individuality also goes along way looking at other similar size studios like us.

Are you thinking about doing conferences and public talks?

We’ve done a few talks before at universities, and we did one for an annual typography event. I’m not super comfortable with public speaking. But I’d like to challenge myself more with it.

FK

Personally i’ve tried teaching, specifically creative coding with some friends but I found it frustrating. I’m not sure I’d enjoy teaching full-time. That said, a lot of my friends in the creative industry are moving into teaching roles at universities. Like having talks, teaching to me seems like a meaningful way to evolve as a creative, being able to break down your process and explain it to others. So maybe that could be something in the future, but for now, not really.

Do you handle everything yourselves, or do you bring in outside help?

We do most of the work—maybe 80–90%—internally. But it depends on the project scale. We do 3D in-house, but if the scenes are too complex or require intricate modeling, we’ll bring in external collaborators. Similarly with development: we’re more than capable to do it, but if bandwidth is tight, we’ll collaborate with other developers as well.

MKB

We’ve built a strong network. We know who’s good and reliable, and we tend to work with the same people again and again.

FK

Some people are so good you’ve got to book them a couple of months ahead. But if you’ve built a solid relationship, they’ll sometimes shift things around to squeeze you in. That kind of trust is super valuable, especially when you’re on a tight timeline and need abit of a last-minute favour..

UI design and site development for the new Balming Tiger website

How would you describe the current creative market, especially among independents?

Last year was strange. It was our first full year doing this full-time, and we were trying to figure things out. Compared to previous years, it felt slower. Clients had smaller budgets and weren’t taking many risks. We weren’t sure if it was just us, but everyone we spoke to said similar things. As for this year—it’s hard to predict. Especially with visual creation and AI—so much has changed just in the last few months. We see it as an opportunity to improve our internal processes. For example, we’ve been using these AI tools to create assets for 3D work, like depth maps or normal maps. But at the same time, there’s a risk. The value of what we do can feel diminished. Image creation, for instance, is now seen by the some in the general public as something that’s quick and easy.

So you’re using AI not just creatively but also to improve workflows?

Exactly. Not on a large scale, but in small, helpful ways. Like if we’re working in 3D asset and need to generate a normals or depth maps, AI can do that very quickly while still understanding the context of the scene. These little tools are great internally but once you step outside of that controlled use, how people are applying AI is very different.

MKB

In the past, the creative market had very strong trends. You could clearly see certain animation styles or graphic design looks that everyone was following. But now, it feels more like a mix of everything. New tools keep coming out, and we are all trying to keep up and learn them. The younger generation especially seems to be able to do a bit of everything. So overall, it feels like there is just a lot going on all at once, and we are overloaded with creative styles and tools.

FK

In the past, if you wanted to improve, you’d try to work with and learn from the best. But now, information, techniques, and tools are so accessible that one person can learn and do a lot on their own. Of course, having the technical know-how is very different from having the ability to create work that feels thoughtful and creatively distinctive. But the gap between knowing how to do something and actually doing it well has gotten smaller. This has created a change where you’d see many more talented young people. It’s also changed how clients see and acquire creative work. For example, 5-10 years ago, you’d have to go to a big agency if you needed a 3D scene. But now, one talented person can often do all of that on their own, which has really shifted the engagement of creative work in the industry.

Shannon Lim

Are you seeing any other changes in your own work—things that you’re excited about, or maybe things you’re unsure of?

Everything feels so global now. A lot of younger designers seem to be aiming for this very international style. But one thing I’ve always appreciated when traveling is how each country used to have its own distinct graphic language. For example, Japan has a very recognizable style, and the same goes for Korea. What I believe will really help designers stand out today is developing a creative approach that feels personal and authentic, something that truly reflects who they are. In such a globalized space, having a clear, individual voice is what sets you apart.

One thing that stands out in our work is how we present to clients. We don’t show finished designs but instead share in-progress work like interactive mockups the client can try. This helps build trust because clients see the work developing as we go. I believe this very personalized approach to each client makes us different from other creatives and is why clients often recommend us.

FK

From my experience working within or with other digital studios, you often don’t get a real feel for the project until the very end. We try to give that experience as early as possible. Even with the first presentation, we already provide interactive prototypes that clients can play. We build or code them in certain ways to make this happen. Our process has grown and improved based on these experiences over time.

If you had to do another job in another period of history, what would it be, when, where?

I don’t really like any of the periods in the past. So I would still work in this time period. But another career that I would really like is to become a cook. I really like hosting and the art of the table. I think it will happen anyway in this lifetime, because I really like food presentation. It’s also related to how to make people feel and taste things but instead of digital, it would be with food basically.

FK

For me, it’s also somewhat informed by my current line of work, but probably a footballer in the 90s era, playing for my local team, the Tampines Rovers. Not that i was any good at it or anything.

But these days I’m into collecting retro football jerseys and I’m really into the visual culture of football. Especially back in the 90s, it was really something. For example, if you look at Japan’s J-League teams in the early 90s, the style is so specific. Even though global brands like Nike, Adidas were producing the jerseys, they were really tailored to the local market and had the distinct style of the region. Likewise then you’d look at local club teams in France or Brazil, even the sponsor logos were very localized. There was such a distinct regional visual identity. Now it’s kind of lost, for example, Puma does a single team-wear template and it gets used worldwide by 100 teams.

So it would have been a dream to somehow be a part of the footballing world as a player in those days.

Are there any books that have helped you personally or professionally?

Lately, I’ve been really into photography books. It’s something I only picked up recently. The latest one I got features three Vietnamese photographers. I love the open-ended inspiration. You can see composition, color, and storytelling all in a single frame.

FK

Not recently, but there’s a book I read a few years ago called Hackers and Painters by Paul Graham. It’s from the 90s, during the Microsoft and Macintosh days, but still super relevant. One takeaway that has really stuck with me till now was about how we shouldn’t be afraid to throwing away our work in its current state, but to start again and then refine. That idea really resonated because i strongly believe that through iteration is where the magic happens. Sometimes you get too attached to little things that stop you from exploring new directions.

Are there any artists or people who’ve helped you in your development?

There’s one person—Daniel Givens. He’s a designer and developer. Early in my career, I cold-emailed him for advice. I don’t even remember what I asked, but he replied with just one sentence: “If I can do it, you can do it”

FK

For me, it’s creatives who blur the lines between commercial and conceptual artistic work—like Raphael Bastide. I admire how they fluidly move between disciplines. Their work doesn’t fit into a single category, it can be poetic, expressive, even in client-driven projects. I try to bring that kind of personal signature into my own work.

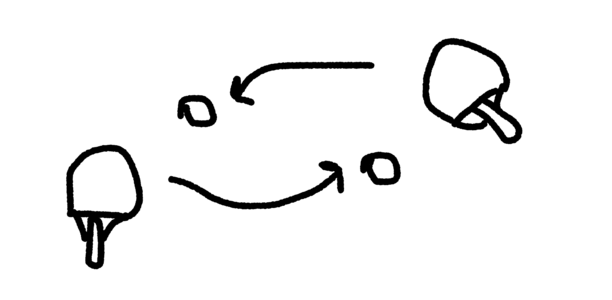

Sketch by Faris Kassim

What’s one piece of advice you’d give to young creatives?

Mine’s practical: always think about financial stability first. When we started OKOK, we both had full-time jobs. Having a recurring income gave us the freedom to build the studio on the side. And of course, trust your intuition, stay positive, and always share your work. Visibility is so important for independent studios.

FK

I used to think one had to wait for the perfect moment to start a studio, like I needed to learn more first. But the truth is, there’s no perfect time. You learn so much by just actually doing it. And like My Kim said, you don’t have to jump all in and quit your job immediately. You can start building your practice on the side, gain visibility, and ease into it. That transition really helped us.