Could you introduce yourself?

I am Pierre Rousseau. I just turned 35. I am a multi-media composer.

Pierre Rousseau

How do you present your work?

I think the title of “composer” works well. I’m quite attached to the idea of composition in a broad sense. I find it interesting that the word appears across so many different practices — photography, painting, and many others. In my professional life, my time is split between a personal practice and commissioned work.

Pierre Rousseau’s offices

How did you begin working in the music industry?

I started making music for a living in the early 2010s with an electronic pop group called Paradis, which continued until the mid-2010s. After that, my work became both personal and commercial. But I never felt entirely comfortable blending those two aspects in the same space. That tension is often central to pop music—it is personal but also commercial, which requires making compromises in terms of image, as well as regarding the context in which the music is performed, in which the work is expressed. Those compromises never suited me. The format of the group also didn’t allow for the sort of personal or radical expression I had in mind. I accepted that for a time, but I eventually felt the need to reconnect with what truly mattered to me. About eight years ago, I made a clear decision to separate my personal work from financial pressure. I began making personal music purely for its own sake. That led to three introductory records, “Musique Sans Paroles” (2020), “Mode Par Défaut” (2021), and “Mémoire De Forme” (2023), a sort of trilogy dedicated to instrumental synthesizer music. It was something I cared about doing back when I was in the group, so I did. Simultaneously, I created what I like to call “hybrid” records, somewhere at the intersection of personal and commissioned work (in collaboration with Études Studio, Arpa Studios and Capsule), which eventually led me to more straightforward commercial work. The collaboration with Études specifically, made me realize I could develop sound, music, and even installation-based work for brands, and more importantly, for image-based projects at large. That’s where my main interest lies at the moment : integrating sound to visual media.

Work by Pierre Rousseau

Work for Études - Twenty Teaser by Grégoire Dyer

How do you think of your commercial work?

My commercial work, though I think “commissioned” remains the better word for it, is really focused on amplifying images. I’m fascinated by the symbolic dialogue between sonic and visual elements, and the history of this interaction. In terms of clients, Études Studio has been central in my development, as has Marine Serre, whom I have created many bespoke runway soundtracks for. I’ve also worked closely with photographers, filmmakers, creative directors, production companies and even architectural designers who’ve opened the door to other clients, such as Apple, Nike, On, Mercedes-Benz or Rimowa. Recently I’ve been working regularly with Chanel, where the artistic direction tends to be remarkably open-minded.

What is your current state of mind?

I feel I’ve reached the end of a development cycle in both my personal and commissions practice. Right now, things feel uncertain, in a nice way, when I try to picture what comes next. What I do know is that, whereas at the beginning of the previous cycle I was trying to create and maintain some kind of aesthetic balance between all the different aspects of my work, today, my mindset is more about approaching each project as its own universe, on a case by case basis. I want a given project to be an opportunity to contribute something powerful symbolically, something that’s both sonically and visually strong, regardless of how it interacts with another thing I’m working on. I want the coherence to come from quality, not from anything else. That’s really where I’m at. It’s become a sort of obsession. On a more personal level, I feel that the core meaning of my life, even before being an artist, a husband, a father, or a friend, is about transmission in the broadest sense. Gaining knowledge or insight, and then interpreting that for the people around me, and those who come after. That is meaningful to me.

Work by Pierre Rousseau - Calvin Klein by Thibaut Grevet

When and what started your interest in music?

I feel like it’s been this way my whole life, to be honest. My father didn’t make a career out of music, but he was, and still is, an excellent pianist. His background is in computer engineering, but at home, I was exposed to two things that completely changed my life: a piano and a digital synthesizer he had bought, along with his record collection. He also had a real curiosity for sound production software, and some of it was pretty radical for the time. There was one program in particular that was, and still is, one of the most complex environments for generating sound with a computer, called Reaktor. Between the ages of 5 and 15, I was immersed in all of that. I started out learning piano as a child, then discovered electronic music as a teenager—both as a listener and as a young producer. I was completely hooked. By the time I was 15 or 16, I already had this strong sense that this was what I was going to do. I was making music all day, and it came to me naturally. I was always moved and excited by it. I did go on to study at university, though—not music, but political science, in England and then partly in Paris. I’ve been living in Paris for the past 12 years, and while I’m not planning to leave completely, I’ll be splitting my time across two cities moving forward, my wife is Danish and we want to raise our first child in Denmark, so I’ll be working between Copenhagen and Paris.

What’s probably most true, beyond what people say, is that there is a real sense of intention behind food over there, even in the smallest things. It’s something we’ve kind of lost in France. I’m thinking of all those boulevard brasseries where everything’s just frozen now. Over there, it feels like people really care, no matter where you go.

That’s true. There’s a real sense of refinement, particularly of interiors and hospitality, over there. What Denmark shares, in its own way of course, with Japan for instance, is a deep attention to the quality of the shared present moment. That’s something I felt very strongly over there, and it brings me a real sense of calm and clarity. So in this new phase of my life, the idea of making it one of my bases for life feels right.

Korg 01 WFD

What are the references that inspire you?

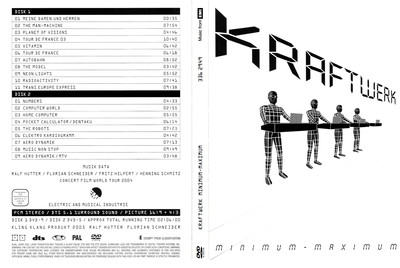

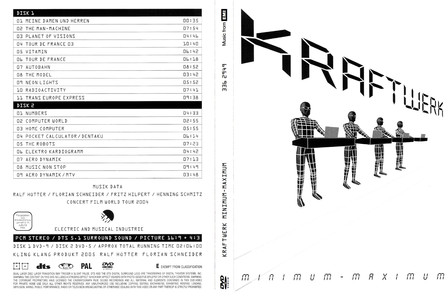

Most of my references actually aren’t musical. The artistic works that have really moved me, regardless of discipline or form, are the ones which have managed to condense and transmit something in a comparable way: they draw from something extremely chaotic and distill it into a sharp formal proposition which feels clear and intentional. I wouldn’t necessarily call it minimalist, just clear. As for music, it’s hard to narrow it down, but broadly speaking, I grew up listening to a lot of classical music. If I had to reduce it, I’d say Bach, Debussy, Ravel, Satie … and later Steve Reich. More and more I’m drawn to Eastern European and Scandinavian composers as well, though maybe we’ll get into that later. Jazz too: In a Silent Way by Miles Davis was a defining experience for me. When it comes to electronic music, Kraftwerk was an emotional shock as a teenager, when I bought “Minimum-Maximum” upon its release, and then pretty much all the German artists from that era : Neu!, Manuel Göttsching, and Klaus Schulze’s label Innovative Communication.

Ryūichi Sakamoto has been hugely important to me too. And of course, Brian Eno. And then Warp Records, Aphex Twin, Autechre, Squarepusher and so on, as well as Detroit Techno, Underground Resistance, Drexciya, Juan Atkins. And previously, the whole wave of experimental electronic music in the U.S., especially the women who led that scene: Suzanne Ciani, Laurie Spiegel, all of that really stayed with me. Then, like everyone, I’ve listened to a lot of pop music, The Beatles, Pink Floyd, and a lot of lesser-known things too. Often with pop music I listen not for the whole work, but for sonic fragments, for specific details or symbolic gestures. For me, these feel more like catalogs of references and techniques, as the grandiosity of pop often doesn’t allow for the sort of sonic intimacy I yearn for these days. The past few years I’ve fallen into a musique concrète sinkhole, and multi-channel “speaker performances”, in large part due to the work of Radio France’s GRM (Groupe de Recherches Musicales).

Minimum-Maximum, Kraftwerk

GRM Console

And what are your references apart from music?

We don’t need to go as deep into photography, painting, and sculpture, but to name a few, visually I have been most influenced by Ellsworth Kelly, Donald Judd, and James Turrell. In France, I’d include Daniel Buren and Olivier Mosset. In graphic design, Peter Saville had a big impact on me. And in photography, so many names of course, but when I was a teenager, discovering Wolfgang Tillmans really shook me. I feel like Wolfgang Tillmans owes a lot to William Eggleston. Actually, I love finding coincidental connections between these different artists, their crafts, their tools and perhaps my own. William Eggleston made a record entitled Musik with a K, almost entirely using the Korg 01W, which is the all-in-one digital synthesizer I mentioned we had in the house when I was a child. The record makes heavy use of some of its most identifiable presets, and brings up core memories in me. I saw David Lynch also uses it for his own music. Wolfgang Tillmans also makes music now.

Korg 01 WFD Manual

What has inspired you recently?

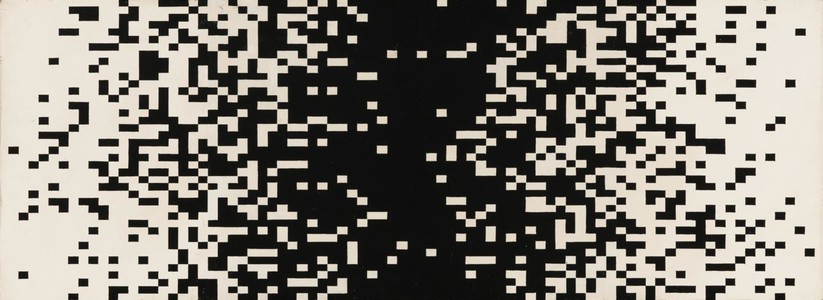

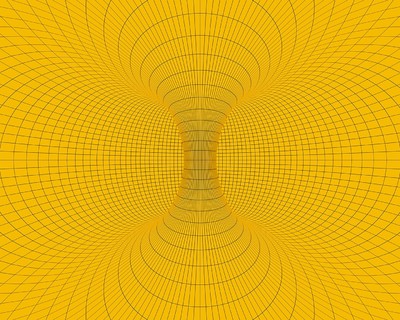

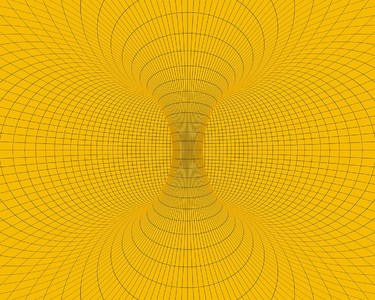

The work that struck me the most this year was part of Ellsworth Kelly’s retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. One of the first works in the exhibit is called Seine, as in the Paris river. For me, it’s exactly what I’m trying to do with music. He stood in front of the Seine one night in 1951, observing the light from passing boats reflecting in the moving water. My very first solo piece of music, called “Anonyme” is accompanied by a video showcasing this sight. Anyway, 75 years ago, he managed to “pixelize” that sight in his mind. He formulated it in his brain and conveyed it by hand, with the imperfections of gesture. A sort of pre-digital impressionism. On a similar subject, I recently realized the early developments by IBM of modern computers, and later drum machines by other companies, were based on a system of punched cards inspired by the Jacquard looms of the 18th century. Discovering that there’s a real intellectual and practical connection between Jacquard weaving and drum machine patterns is something I find fascinating. It’s this kind of topic that I want to explore in the coming years.

Seine, Ellsworth Kelly

You created a polymorph career for yourself, there’s purely artistic work, there’s commissioned work, and in both you can bring in more or less of your personal or artistic voice. Is that something you had planned out from the start?

It all came together in a very organic way. For me, it was unimaginable to work like this at first. And I have to admit, when I try to explain this kind of approach to younger people coming up, it’s sometimes hard for them to grasp. Creative practice, artistic practice: those terms are quite blurry for a lot of people. But the truth is, being creative doesn’t necessarily mean making art.

What I mean is that you don’t experience it as a split or contradictory process.

That’s true. I think today I’m able to carry both of these things at the same time. And that’s because I’ve made a real effort to understand what’s at stake in each case. What I mean is that when I’m working on my own practice, it’s about personal exploration, with the hope of moving someone else in the process. But when I’m responding to a commission, which I do quite a few times a year now, it’s really about understanding the client’s needs first and foremost. For me, that’s how I honor what is, in the end, a transaction. I don’t necessarily see it as the appropriate place for my personal artistic expression, unless I’ve been asked to work in that capacity. Rather, it’s where my conceptual, emotional, and technical background can meet a specific need. I try to identify that need, understand the internal hierarchies within the project, and figure out what matters most to everyone within that structure.

Work by Pierre Rousseau - Arcteryx by Marvin Leuvrey

Did you approach it from a strategic point of view? Was there a turning point when you thought, whether for financial reasons, or maybe to open yourself up to new perspectives, that you wanted to take on commissioned work?

Yes, there was actually a very specific moment. The record industry model we’ve known, the one which has existed between the post-war boom and the arrival of Napster, was, in reality, just a brief parenthesis in the history of music. It lasted maybe fifty years. Out of that moment came a system where, today, only two kinds of artists really manage to thrive financially within the traditional music industry: performers, or those with a very pop-oriented proposition which can generate a large streaming revenue without too many middlemen, which is extremely rare in an age of artificial algorithmic manipulation. But for the kind of music I wanted to make, and the way I wanted to do it, spending most of my time experimenting in the studio, the traditional model didn’t feel realistic or sustainable. There are a few counter-examples in more experimental circles with very desirable careers, but I feel those are rare exceptions. I eventually came to realize that outside of this model, there is an ocean of possibility for music and sound, beyond just selling records or going on tour. I genuinely believe music and sound are everywhere, all the time. What I try to do now in my commissions practice is to help clients understand the power, or at least the value, of sound and music. In a way, before the record industry, that’s how composers have always earned a living, creating bespoke music, whether for Operas or Requiems, etc. Those commissions just take a different form in today’s broader culture.

And it’s a great formula. What did you have to learn in order to manage what you call, rightly so, clients?

The most fundamental thing, as I keep coming back to, is understanding the stakes. Understanding the structure, even the purpose of a campaign. A global campaign for the launch of a shoe by a leading sports brand is very different from a short mood film for an independent craft-oriented company. The budgets aren’t the same, the approach to creativity isn’t the same, and the relationship to effectiveness is different too. It’s about understanding the nature of your involvement. Too often, creatives can make the mistake, without realizing it, of confusing a commercial commission with an exhibition show. It’s not the right place for that. And that’s been a learning curve, it didn’t happen quickly, if I’m honest. It took me three to five years to understand hierarchies and realize it was all about embracing the needs and concerns of the client. Very often, the client is worried about handing over their project to creatives, especially when they talk a lot, like me. The first step is about reassuring them and making them understand that their needs come first—as long as they are not in direct contradiction with my process. Once that trust is established, then you can start introducing strong, creative ideas. Sometimes, it’s not necessarily about compromising, but simply deciding that maybe this or that idea isn’t the best suited for the brief. I feel infinitely freer and more capable of offering things that I find truly relevant, particularly today, compared to a few years ago.

Napster

I imagine you started quite organically, with the first network around you. But at some point, did you told to yourself you needed a strategic plan?

Not particularly. I still believe it’s extremely organic and that it’s primarily about people getting along well. There’s no particular conquest strategy. There’s no prospecting activity.

Is this a strategic choice?

It is! I prefer to operate this way because I believe that if things aren’t optimal with a director, an artistic director, or a client, etc. it’s just not meant to be and there will be other opportunities. However, what’s important to me, and what has become a strategy, in order to provide creative clarity for myself and others, was to separate my personal practice from my commissioned work by creating an “office” called Stereo Image. This platform now hosts and communicates about commissioned projects, simply because I realized that for all the reasons explained earlier, the approaches are too different between creating art and responding to a brief. It allows me to show a lot of commissioned work without entertaining too much confusion with my personal work.

Stereo Image’s logo

When it comes to strategy, aside from your artistic and creative references, were there any other people or examples that inspired you in terms of managing their careers?

I’ve always been interested in multi-faceted creatives and studios. I’m particularly influenced by graphic designers. We talked about Peter Saville : he is truly someone who fascinates me. The way he reasons to find solutions to creative challenges … I’ve probably listened to all of his interviews available on YouTube. I’m also really a fan of those multi-polar careers in music. So we talked about Ryūichi Sakamoto and Brian Eno, these are people who brought solutions in sound and music for campaigns and products (Sakamoto created sound design extensively for Nokia, Eno collaborated regularly with Microsoft). But I’m also very influenced by people who helped me see what I wanted to do much more clearly. We spoke of Études, particularly Aurélien Arbet, with whom I host a show called Wave Form on NTS, as well as Marine Serre, but I must also mention Thomas Subreville from Ill Studio, as well as Arthur Van Peteghem, who has a company called Avoir. Bas Van Der Poel from MODEM. And many other creatives from my generation, honestly, I couldn’t list them all now, but: my friends Helena Kadji and Rocio who have a studio called Faye & Gina, who have designed my graphic identity from the beginning, Tristan Bagot who made my website, Marcelo Gomes and Charles Nègre, who have shot some of my press portraits. I am also in awe of the accomplishments of Felix Ward and Pierre Dagba from Matière Noire, as well as Cyrus Goberville at Bourse de Commerce, Pinault Collection. I’ve never worked with graphic designers Axel Pelletanche and Antoine Roux but I think their work is exceptional. I also love the CGI work of Amine Ghorab and Scott Renau from Area Of Work, as well as my friend Valentin Gillet. I love people who make themselves available with their talent to find solutions for others. All the people I haven’t mentioned will certainly feel left out because there are plenty of others, but it’s what whom I can think of off the top of my head.

New Order - The Peter Saville Show Soundtrack

How do you work to manage all of this? Are you alone, or do you have people who help you?

I have a partner who is both my business partner, my agent, my manager, and my informal psychiatrist, his name is Alexandre Gaulmin. I’ve been working with him for 10 years.

How did you happen to work with him?

He came into my life because he was working in the communication department for my previous band’s touring company. He found himself in a meeting we had at Universal. I felt that he was the only person, no offense to the others in the room, who openly stated the obvious about the situation at hand. He didn’t hesitate to break the convention or hierarchy of the moment to say, “This is not working, we can’t do that.” For me, that immediately created a sense of trust. He then became the manager towards the end of the band, helping us restructure everything in a very diplomatic way. After that, he allowed me to structure my next projects with a company. Initially, the company was set up to manage my music career. In the first few years, right after, I mostly focused on producing music. I worked a lot with Nicolas Godin, who is half of Air, and with whom I currently share a studio. At the beginning, the company’s purpose was mainly to manage that. When the commissions started coming in, it evolved into a production and editorial management business.

Work by Pierre Rousseau - Louis Vuitton by Shayne Laverdiere

I imagine that when you have client commissions, composition sometimes comes at the end of the project. The images have already been shot, the scenography has already been decided. In addition to the clients on the brand or commissioner side, you also have set designers, art directors, and other people involved in the loop. How do you both manage that?

I manage the entire creative aspect, while he manages the entire administrative and business aspect. As for the timing and schedule, I manage that, because in reality, it’s very difficult to plan ahead or to delegate scheduling, you just have to be very flexible and reactive in this business. Sometimes an idea takes two minutes to come, and sometimes it takes four weeks. So I don’t think I would ever charge by the hour, for instance. I charge for the end result. However, what I do is define a set number of interventions on a project. The point you raised about music arriving at the end of the process is less and less the case, as I’ve built long-term working relationships and I’m involved much earlier these days.

Is this a new phase for you?

I’m asked earlier now. I see the creative deck early on. Often, I’ve even proposed something before the film is shot. That’s great. And most importantly, I’ve started to get to know the network of editors and built good working relationships with them as well. 80% of my commissions are campaign films. And for that, it’s often the same pool of editors, dedicated to certain directors, certain production companies. We pretty much know what works and what doesn’t. There are ways to make projects very simple and effective, and ways to make them extremely tedious and inefficient. Unfortunately, sometimes things get messy, but we can’t blame a production company for not fully grasping the complexities of each process involved, particularly when these “international” teams, located in different time zones, have been set up so quickly. I try to point out any potential issues from the start and express them. That way, they don’t become surprises later. Last year, out of about 30 projects, there were only one or two where things didn’t go as well as expected, I’d say that’s a pretty good ratio. The language used to talk about music and sound is extremely difficult for most people. So, I’d just like to emphasize that today, the key skill I’ve acquired is almost like that of a translator, even more so than a composer.

I’ve realized that even in fields like design, strategy, graphics, or art, you need to build some kind of shared language pool. I read an article about wine terminology last year that had a huge impact on how I think. Even in three-star restaurants, when two sommeliers talk to each other, they don’t describe wine the same way. If you ask them what “powerful” means, or what “freshness” means, they each have their own definitions.

Exactly the same thing happens in music. Actually, it’s funny, but also a bit sad, because you realize a lot of people are afraid to use their own words. They’re scared of getting it wrong, which can create big misunderstandings in creative loops involving sometimes a dozen people. Just to loop back to the wine example before returning to music: when I was younger, a sommelier once described a bottle during the height of the natural wine craze as having “a bit of chili.” I thought that was a great way to describe it. I’ve reused that expression, it clicked for me.

Work by Pierre Rousseau - Chimi by Thibaut Grevet

Yes, I’d say “peppery.”

Exactly. But when I’m looking for a bottle, I’m like “sorry, I’m gonna sound ridiculous…” and people laugh! The same thing happens in my work, 90% of the time, when a creative director or a production lead briefs me, they’ll say, “Okay, just a heads-up, I don’t have the right vocabulary. Tell me if I’m saying it wrong.” They always apologize, so I tell them there’s no such thing as a wrong word. It’s my job to try and understand what you mean. But honestly, the two most problematic words in my experience are “rhythm” and “intensity.” “Rhythm” is tricky. For some people, it means percussive sounds. For others, it’s about tempo or pace. It can also refer to the density of notes—like eighth notes versus sixteenth notes within a bar. Or it might mean how the tempo evolves over time. When someone says they want more rhythm, they might mean they want it to go faster. There are just so many ways to interpret it. And “intensity” is a very cultural thing. I had a moment early on, one of my first commissions was for an Issey Miyake runway show, about eight years ago, when the designer kept asking for more intensity. I kept adding sounds, layer after layer, thinking I was getting closer. I eventually asked me to show me a point in my existing version which felt intense to him, and he pointed out a moment which was almost silent. I eventually realized that for him, intensity meant suspense. That taught me a lot. One of the projects I’d really like to work on in the next few years, maybe with a design school or a small publisher, is a short A-to-Z of sound and music terms for creative directors. I think it would be really helpful.

How do you shape your image when your work is in sound?

Honestly, it’s very instinctive. I just have a strong sense of what I find beautiful and relevant. When it comes to my personal work, visual expression, whether it be record covers or film content, etc. is key to contextualising the music. It forms another layer of comprehension for the listener. I always try to look for contrasts in the interaction between image and sound. So, for instance, if the music I have created is very digital, clean, and “organized”, I like for the images accompanying the music to be quite a bit rougher. Conversely, in anticipation for my next release, where this time the sound is on the “dirtier” side, I am working on a more “high-definition” visual environment to encapsulate it. When it comes to the commissions practice with Stereo Image, 90% of the reason for taking a project is whether I find the visual environment to be strong. So that forms a coherent image for the “office” quite organically. I’ve also cared about developing a graphic universe with Faye & Gina, which involves logotypes, typefaces and general reflexions on “form” in order to narrate the differences and commonalities between my personal work and the commissions practice, which we outlined in a short “graphics standard manual”, and which is something I have always found fascinating in the corporate world. And then, there is the visual expression which one is able to engage with through social media, which I simply use as a continuous stream of more or less relevant “behind-the-scenes” content, which gives an additional layer of context for the work. Thankfully, the social network I use the most, Instagram, lets you structure visual expression on two levels, with different degrees of importance. You have ephemeral content, and then your main feed, which acts like a sort of micro-gallery. In the early days of Instagram, the feed felt more like a series of press releases. Now it’s more like a fast- scrolling overview that gives people a quick sense of someone’s mindset. I’ll post things, and over time, I’ll rearrange or archive them to make sure they still make sense together. It’s a way for people to quickly understand the perspective I bring, it “sets the scene”, in a way. Stories are a way to share, and preview, things instinctively, something graphic, a book excerpt, a reference, and they spark connections. People reply, “Hey, how are you ? Long time! You’ve read that book too?” And that kicks off a conversation. Then there’s a second account, which is for the “office”, Stereo Image. That one’s more about showing the coherence in the visual projects I like to be involved in, because I feel like my way of working is more suited to certain types of imagery. And it’s important for me to highlight that. I’m lucky to work with people whose visual worlds really resonate with mine.

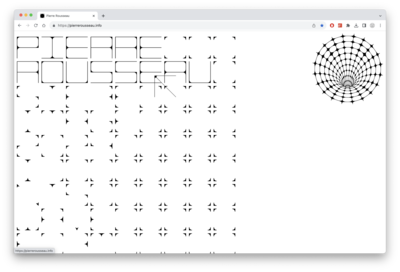

Pierre Rousseau’s Website

If we zoom out a bit more and look at your profession as a whole—whether we’re talking about your artistic work or commissioned projects—are there any evolutions that worry you? And are there others that you welcome with open arms?

I wouldn’t say I’m particularly afraid of anything, to be honest. From a professional standpoint, I see every field as constantly evolving. I actually welcome AI with enthusiasm. I know that might bother some people, but despite caring about my own technical ability, I’ve never believed that the artistic gesture or creative solution was primarily a matter of execution, it’s really about ideas first and foremost. So for me, AI is exciting because it allows time for me to focus on new, different things. It often offers solutions I wouldn’t have thought of on my own. I never wanted to work the same way forever anyway. I genuinely believe the essence of any artistic or creative proposal is resonance, with a human perspective, a creator’s point of view. And you can feel it immediately when something wasn’t made by a human, it just doesn’t resonate in the same way. My next point has become a gimmick at this point but: we don’t watch computers play chess, although they are far superior players. I consider myself quite sensitive, so if an art work doesn’t affect me emotionally, that tells me a lot. What does concern me more is the future of musicians in general, based on the state of the industry I was describing earlier.

Work by Pierre Rousseau - Atomic by Thomas Van Kristen

You mean the people who actually practice, right?

Exactly. As I was mentioning earlier, I see fewer and fewer viable paths for people who are neither performers nor pop artists to build sustainable careers. I haven’t personally felt this pressure yet, but I think we’ll inevitably see increasing economic pressure as more people try to enter the field. I feel like we’re in a moment of confusion about the meaning of certain professions, industries, and how their value is understood. I feel a kind of responsibility, and I think it’s necessary,to advocate for the value of composers’ work. But it’s not always a natural reflex for creatives to think in terms of the value they create. That’s a point I’d be very happy to elaborate on later, it’s important to express it properly. And the other reason I’m not overly worried is that, if we think in terms of creating value, not just extracting from a finite pool of jobs or resources, I believe there are infinite projects to be created. Projects don’t just exist; you can spark them into being if you express clearly that they are possible. There will always be a need for music, always a need for sound. That being said, it’s all about being surrounded by honest people—because rights clearances, for example, can vary significantly depending on the release scope of a commercial campaign. For example, there have been times, I’m not saying who, when, or even if it involved me directly, where I have heard of someone commissioned to compose original music for a campaign destined for social media. But when the client changed their mind and decided to also clear the rights for TV broadcast, the client’s legal team instead opted to use a “library” track which sounded a lot like the original composition which had been created for the social media campaign, perhaps using an AI-powered search engine offering access to a library of similar tracks, effectively removing the need to pay the composer for their development work. There’s no real legal issue, technically. But that’s the kind of practice that falls into the realm of questionable ethics, since the search was made possible by the composer’s development work. Honestly, if the broader economic environment becomes increasingly unethical, I don’t think I’d have much interest in working in it anymore. Life’s too short to spend too much time in unhealthy work environments. Let’s see. I don’t think it’s in the long-term interest of high-profile clients to work in this way.

Work by Pierre Rousseau with Modem Works

Having worked in advertising, I’d say this kind of thing has been around for a long time—maybe even since the early days of advertising, in the ’50s. There have always been music production companies that agree to recreate a track just close enough that it doesn’t qualify as plagiarism.

It’s a longstanding practice, and to be honest, I don’t find it especially objectionable artistically. There’s always a spectrum of how close a creative gets to a client’s references, whatever the context. Personally, though, I’m just not at all interested in reproducing tracks. You can always replicate the form of a piece, but never its soul, so what’s the point ? You simply can’t. When I talk about ethics, I’m more concerned with something else: for instance, intentionally reducing the number of people involved in a creative process. That’s a current trend, part of a broader economic paradigm, but it also reflects a certain ideological stance that I find questionable. Music, in particular, has suffered a lot, not necessarily because certain styles no longer require the same breadth of specialized roles, I get that you don’t need five different sound engineers and arrangers to make an Aphex Twin track. But for some music, it’s no surprise that the overall quality has taken a hit, when all the skilled professionals who used to make that kind of music possible as a group are no longer involved or budgeted for. That does worry me a bit. But again, maybe I’m not the best person to talk about this, since I work mostly alone.

Work by Pierre Rousseau - Latimmer by Anton Tammi

If you could do any job at any time, what would you do?

I don’t think I could have had the job I do today in a different era, not only because technically it didn’t exist, but because, for me, what enables me to do my job is the computer. I actually feel much closer to coders and graphic designers in my daily life than to composers from the late 19th century. I’m driven by the emotion of sound clashing together in much the same way, but I would have been completely unable to do the job of a composer 100 years ago. So, if I had lived 100 or 150 years ago, the job I would have had would probably have been something more practical, something related to craftsmanship. I’ve always been fascinated by craft-based professions, things like carpentry. It’s not impossible that one day I might pivot into something else. We’ll see how things evolve. Perhaps I could have been an industrial designer, or a writer. I love the work and career of French industrial designer Roger Tallon, for instance.

Module 400 Chair by Roger Tallon

Is there a book that has helped you in your development?

We briefly touched on the question of symbols. It’s a word I could have used more often throughout this conversation. But the book that changed my life is Mythologies by Roland Barthes. He’s one of my internal voices. I should have mentioned him earlier when talking about influences. When I’m not feeling well, I listen to an interview from the 70s, which is available on streaming platforms. It’s called Fragments de Voix, from 1974, where he goes through many themes that are dear to him. What strikes me about Barthes is how deeply connected his work is with themes that have moved me throughout my life. The fact that he wrote major works on signs, symbols, Japan, photography, the piano, love relationships, the fashion system ; these are all subjects I have cared about at some point. He also has tremendous clarity in his oral expression, which is something I admire.

Conference by Roland Barthes

And the final question is quite simple, what advice would you give to a young person interested in a creative career or composition?

It starts with my biggest regret, which is not realizing sooner that perfection is impossible. Simply because in life, there is no destination. Everything is always in motion. So, don’t wait too long to express what is important to you. Just express it, and let life unfold. It’s fun.

Pierre Rousseau’s logotype

I’m quite the opposite. There has to be a plan and a destination. Then, that allows for improvisation. You almost need a framework “here’s what I want to do in 10 years”. It may never happen, but you have this idea and can think about what you need to do to get there. Other things you can’t predict will happen along the way anyway. One of the mistakes many people make is considering their situation and evolution in an “other things being equal” context, whereas everything is always in movement.

It’s possible that we’ve expressed the same idea in different ways. For example, and this is a bit grim in the current context, but historically, the best military strategists have been those who understand that an objective is always a moving target, that there cannot be a fixed objective. I think there’s a stage in life, very early on, where you have to go all in on mastering a technique. That phase lasts a long time, to truly master something. But then, you have to let go, let it live, let it collide, let it make mistakes. I think that’s really important because life is enjoyable when it’s chaotic. I’m convinced of that. I’m becoming a kind of chaos enthusiast. It’s a scientifically neutral word but which carries a lot of weight, especially today when it seems nobody is in charge anymore, but it really resonates with me. And after that, I have a much more practical piece of advice : live below your means. You never know what’s going to happen.

Sketch by Pierre Rousseau