Could you please introduce SG?

SG is a studio that couples the creation of visual identities with production capabilities. Our creative discourse is easily identifiable; it resembles us and is present in several sectors of communication in the broad sense of the term.

Portrait of the SG team

Could you introduce yourself over again, please?

We are a cross‑disciplinary studio based in Paris, with a dozen or so employees. Our creative design services across varied media (image, object, space) are mainly geared to high‑end markets: fashion, tech, and beauty products.

Portrait of the SG team

What is your current state of mind as of January 2021?

Expecting some kind of change that is slow in coming.

Are you still looking beyond the six coming months, or do you need to rethink your strategy?

Both propositions are true and not mutually exclusive. We have long‑term projects that we must remain focused on, such as our new annual SG project, “Oasis”. We have launched a new prospecting campaign, in part because we had already decided to do so, and also because within the current context you’ve got to stay punchy.

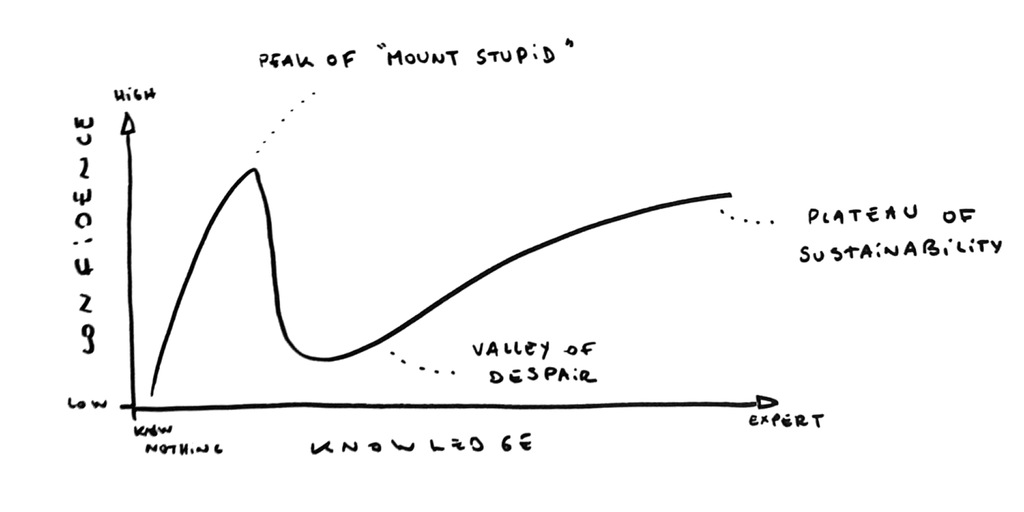

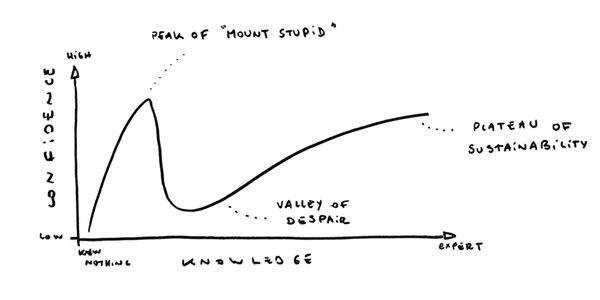

A

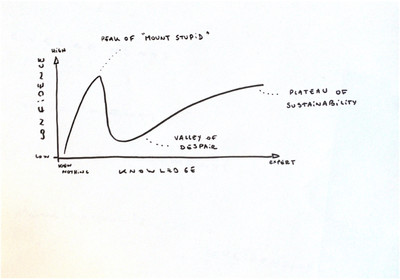

We’ve been lucky enough to always be able to think six months ahead. You guys taught us that we needed to get into prospection and development. It’s become second nature for us, we’re prospecting in places that attract us. Rather than months, we’re more focused on years. We feel that SG has just left babyhood behind in terms of development, a phase where we were very keen to know about everything. Now we’re thinking of the teenager to come. We’ve been trying to keep doing what we’ve always done: go as slowly as possible while taking the greatest possible steps to be ahead of the curve.

Sketch by Antoine

Sketch by Antoine

What were your visual, artistic, and technical influences starting out?

I had lots of idols in lots of various areas and all had quite different artistic qualities. There were the people who were “simply” talented, and the geniuses. I enjoy both without distinction. Pierre Soulages for example thanks to whom I got into painting and who got me into Fine Arts. I especially admire his longevity; Pierre Soulages, who will be turning 102 this year, can keep on painting, it’s obviously so intimate and sincere after all this time that you can’t help but pay attention. Then there are people like Kanye West who despite the whimsical mega superstar aspect of his life has had an extraordinary career. What he has brought to music is amazing, first as beat‑maker, and very early with his comments on homophobia in rap, his activism and artistic vision which some people have made fun of but that ended up becoming huge after Yeezus. He’s a real “creative director” in the literal sense of the term. I could name a whole bunch of people: Jane Goodall who studied primates in Africa, the German painter Gerhard Richter who is literally, absolutely incredible. On a much more personal level, I can’t help but name a studio that brought all of this about: Ill-Studio; they’re not that much older and yet they blazed a trail for us with their cross‑disciplinary approach and the numerous self‑initiated projects that define their artistic discourse. We have invented nothing; our friend Willo Perron also knows how to do this stuff.

V

Meeting Antoine really broadened my creative horizons. I was halfway into creativity and halfway into technique and could have ended up in an engineering school. Though Antoine and I share certain visual references, I’m also perfectly capable of digging an aluminium profile for example.

How about today, any contemporary influences?

I’d stick with the same names. Unlike Valentin who specifically loves images regardless of their originator, I happen to be interested in the person’s story. I have idols and tend to stay faithful to them over time. Sometimes I’m impressed by certain young creative designers or young studios, but there’s not a one that has in my opinion “broken the internet” and therefore entered the “idol” category.

You’re curious about their lives, yet you both hide behind a brand name.

It’s not a question of hiding, it’s just the embodiment of our work, since there are two of us. We don’t want one or the other of us to be the face of SG; it’s our body of work: the artistic direction, the vision. Every aspect of our discourse is managed and the image of the studio never overlaps or merges with the image of a person.

A

There is a little bit of hiding to it though, I think. On a more human level there’s also modesty, shyness, our laid‑back approach. And of course, cynically speaking, lack of personal branding is a form of personal branding…

Augmented Sense in collaboration with Johanna Joskowska, 2020

How do you maintain your creativity?

That’s an excellent question and one that reminds me that we haven’t been doing enough. We don’t enjoy the advantages of being in one of the great cultural cities of the world, Paris. When we launched SG I had a stiff, collector‑like approach: I collected images that I put into an image bank, with tags. It became a kind of monster with more than 5,000 or 6,000 filed and tagged images. I used Google Photos, which you normally use for family vacation photos but is a tool that recognises fabric, colours and people, and lets you tag them. Also, thanks to the metadata you can also identify different time periods thanks to the grain of the image, type of camera, etc. I added my own tags that are adjectives, words, atmospheres. I’m very rigorous about it, so when Valentin and I are brainstorming I type in two or three tags and stories flow out of the images.

V

Often you already have the visual in mind and hunt it down to show me.

A

I copy, within reason of course, Raf Simons’ way of communicating his creativity to his teams. I don’t draw, I create image notebooks that I blend together. A single image is not the same thing as five images side by side. Honestly we’re currently using what we’ve saved up, because we’re so full up with work. We don’t go to enough exhibitions, movies, we’re missing the stories and things that usually stimulate creativity.

V

During the last week of 2020 we met at the studio before everybody else so we could have a calm, creative work session before the clients got there. We ended up talking about lots of stuff but we didn’t come up with any ideas, we were all dried up. We realised we needed to take a break, do something else and then come back to it.

So there is a time for creative resourcing?

Yes, you need to have material set aside. If you have a thousand ideas per second, it’s because you’re always coming up with the same thousand ideas.

V

It’s an effort you’ve got to make, an awareness. Antoine’s contribution is conceptual; his approach is extremely visual. Mine is no doubt more informed by methodologies of production and reflection.

Antoine, could you tell us a little about the relationship between aesthetics and concepts? You work a lot with images whereas certain artistic directors like to write out their ideas using their principles of construction…

As I grow I find I’m becoming a little like that, even if I’m not sure I like it. At first I was exclusively

visual and was always telling Valentin that I didn’t have any stories to tell, that I just wanted to show things. I have no problem with the gratuitousness of beauty, really. I see in it a form of humility, of withdrawal, that I find rather elegant. However, recently, especially since Valentin remarked on it, it’s changed a little and the idea of a story, a narrative is now more central to our practice. And yet, even if it doesn’t sound very intellectual, the fact that something is beautiful interests me more than wondering whether it’s interesting or not.

V

We have a tendency to always concentrate on the visual aspect of what we’re doing and to master every aspect of it before producing it; it’s better for us to supply the visual references rather than having to explain them.

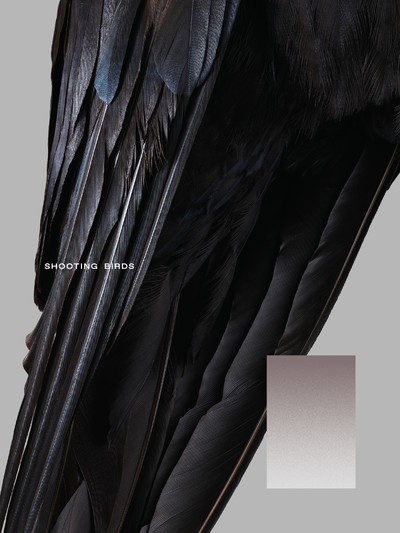

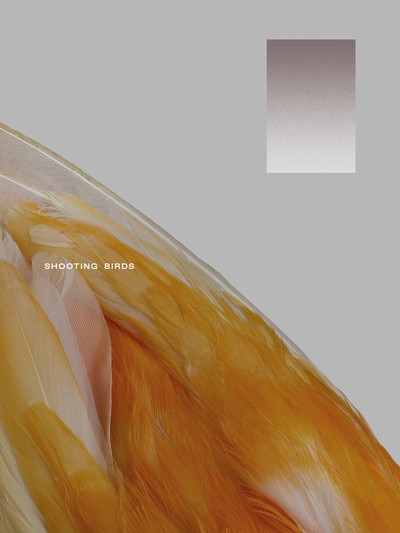

Shooting birds, portfolio work, 2020

Shooting birds, portfolio work, 2020

What you’re saying is that you have a visual vision which is filtered first through Antoine’s creative conception and then through Valentin’s technical conception, and that’s what your style springs out of?

Exactly. For example we’ve decided to make an object with a rather tech look to it, like in the early aughts, with a soft typology of soft materials, to lend contrast. I give a package to Valentin full of images and references, and then he mulls it over, we have a conceptual debate, and then he designs. Then the whole team springs to action in order to bring the image and object into existence.

Are you saying that you’re just an old‑fashioned artistic director?

I don’t know what that means exactly. But our friend Willo Perron summed it up rather well, he says: “my job is to point at shit”.

V

The editorial series we make are a perfect illustration of this: Antoine, or me or someone else on the team wants to work on a given subject, a visual intuition or idea. Then, quite organically we begin to query the potential of that visual and its story, what it reminds us of in terms of references. Antoine came up with the mini‑series Ropes. We thought there was something to be done with that formal vocabulary. Then we take it apart, query what is interesting about the image: the fuzz on the surface of the rope, the minuscule raised fibres, almost skin tone colour, the interaction between two ropes when they bump into each other and the cloud of dust or the patterns they produce when we roll them out on the floor. Once we have taken apart conceptually what could be interesting visually, we redo a reference phase to talk about it, then a phase of sketching to build what we’re going to produce.

A

It’s a series where Valentin starts with a visual intuition: he tells me it looks nice but is meaningless, so we need to work on it editorially. I hate being deprived of that gratuitousness, but he’s right. I love what Ben Gorham, the founder of BYREDO says: that he makes his money with perfume and reinvests everything in the narration, because the stories he tells will always contribute to better defining the brand’s conceptual and artistic identity. For example, he can allow himself to do an exhibition about ornithology, Rare Byrds of a Feather, on which we worked and where he presented binoculars and other BYREDO ornithological equipment. The products are magnificent, very relevant, and help define the brand. Those are the bricks with which he builds the seduction and the influence that BYREDO has over us. It’s a little bit this type of path that we would like to take. We’ve been trying to stop making things beautiful for the sake of beauty, and to be more invested in the narrative.

Ropes, 2021

At the end of 2016 where did you think you’d be five years later, early 2021?

At Christmas 2016 we were at Valentin’s. We had a first freelance gig for Sonia Rykiel that went very well. A few months later we had another, then two, then three, then too many to be able to continue working as freelancers. By the spring of 2017 we had a conversation in Valentin’s basement, literally. I shared with him the vision I had had for years, and that I had even tried to set up with other friends previously: launch a studio, a structure, a tool of sorts that would allow us to take on all possible creative projects with things we love; a structure that would be financially sound and offer us the necessary resources to do what we’re doing today. For example the project (Auto)portrait is a collection of eccentric self‑financed art objects; another example, ordering 15 tons of hand‑coloured sand to fill an entire gallery in the heart of Paris and produce an artistic installation - It almost happened for real, we bought 15 tons of sand. We were supposed to do it in 2020 but the Covid disrupted our plans; or also renting a luxury car to make a technical and artistic performance while driving a little too fast on French roads. So I shared that project, that dream with Valentin: I don’t want us to be graphic designers, or directors or whatever… but rather an entity in which if we have a great product idea, we make it, design it, produce it and sell it. Or, if one day we decide to make an unsellable concept film, we can do that. I felt like I had hit a nerve, Valentin’s eyes were starting to shine. We decided to go for it.

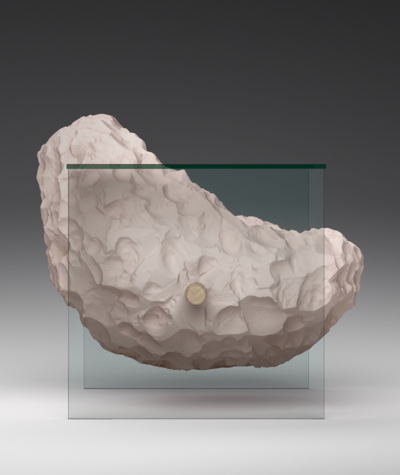

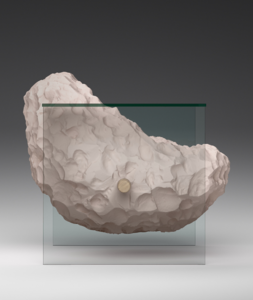

(Auto)portrait, SG exhibition, 2018

That was the vision. What strategy did you use to succeed?

No idea. At the time I completely underestimated the entrepreneurial side. I relied on confidence and ambition. We just worked harder than the others. At the very beginning we had a white label client who gave us a lot of work, and we were completely dependent on him. We had to wait for the next project to buy a computer, for example. These were baby steps, but we were clearly heading somewhere. Rather early on Julien Morin from the 5 fruits / 5 services studio told us we would do well to meet two people specialised in guiding young creative designers… you! And that confirmed the things we already knew we had in us, because our parents have that ambitious plucky side. As for me, my father also owns a design company so I’m surrounded by people who have created their own job, their own structure. When I was young I didn’t focus on what it meant to be an entrepreneur even if I had a bunch of examples to hand.

V

Without necessarily formalising things in a five‑year plan, we intuited that SG would become what it is today, without the slightest idea in terms of time or direction. Today we realise that it was a very quick process. Antoine has said since the beginning that he wants SG to grow but not expand, and that we would never have more than 15 employees because all creative decisions had to stay in the hands of the two founders, halfway between ad agencies that have a million different projects with a ton of artistic directors and a watered down creative output, and the relatively small studio with a clearly defined specialty that people contact them for. Today we realise that growing doesn’t preclude expanding. We’re able to take on more creative tasks while delegating more and more of the production.

A

From the get‑go we knew that we didn’t want to be the Paris “cool kids” – a flash in the pan devoid of vision, financially unstable. We were concerned about longevity, like Karl Lagerfeld who said: “popularity is an autumn leaf blowing in the wind”. Among the “cool kids” studios of these past few years, some have settled down and become gentrified and are producing very solid work and making lots of money. But first of all they’re rare, and secondly they’re no longer cool. Very early on we wanted to make money so that the structure could give us the freedom to do exactly what we want without becoming less relevant creatively speaking. Sometimes we take on very commercial projects that we’re less fond of in exchange for the money and time necessary to produce Oasis, (Auto)portrait, Maison – the projects that really define us and that we love doing.

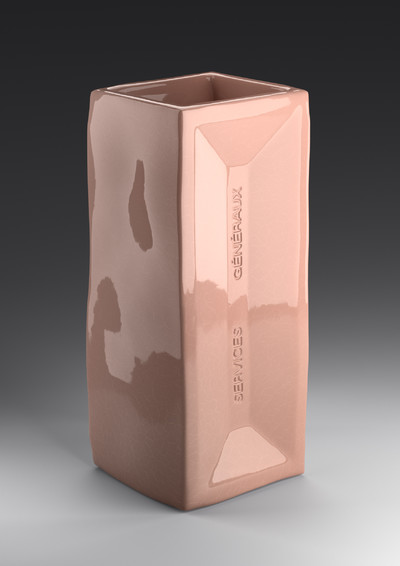

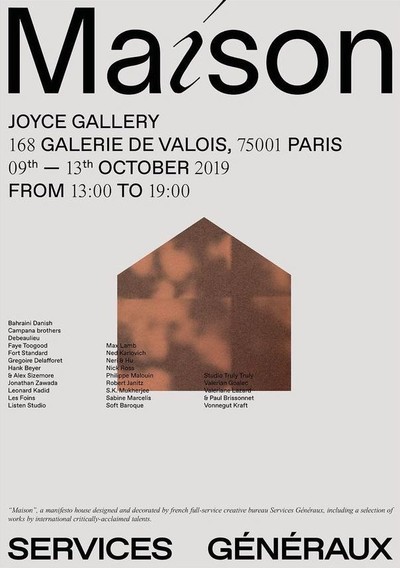

Maison, a manifesto house 2019

How did it happen, in less than four years, that you’ve gone from thinking six days ahead to six months to 10 years?

We’re very ambitious, and in Antoine’s case it’s even a lifetime project. It could have been SG or something else, he would have fought tooth and nail for the project to come to fruition, regardless of the form it took.

A

I’m not sure it could have been something other than SG, if not the name. I don’t know if anyone can in all honesty make a ten‑year forecast, but I can attempt to be more precise in my response to the other part of the question. To make more than a six‑day forecast, you need money. When you bag your first 10,000 euros project, you say to yourself: “that’s it, I made it”, and you start to think in terms of months. Very quickly however you realise that the horizon is not so distant. Our first year we met our financial targets before June, so we said to ourselves that the rest of the year was a bonus. And that bonus is a horizon that stretches out in years. It means less stressful deadlines, a little more time to think about how we’re going to evolve, how to make more money in a given amount of time by gaining more visibility with more ambitious projects, etc. With money you have the comfort of time and reflection and therefore creativity.

V

We wanted to create value with the SG signature before we ever had regular commercial work and this desire is synonymous with the development of the company. We have always known that we want to sell value (intelligence), not labor (energy). In order to increase that value in a certain amount of time, we have to bet on our increasing popularity.

Bling, Value Chain by BYREDO and Charlotte Chesnais, 2020

Sketch by Valentin

What you’re describing is a struggle to avoid your brand image being defined by your commissions. Just like a branding studio who would look for different clients than just the industrial ones it has in its portfolio ?

It’s the perfect example, the branding studios. You have to be a tiny bit “agnostic” in terms of style if you define a new style for each project. There are studios where this isn’t a choice and it just happens organically.

A

Even if we are a commercial studio, we’re focused on being creators. We want to have a limited number of employees, which means that we’re very limited time wise. In order to grow our business we need to undo the connection of labour to value. The labour we provide is finite, but the value has to be infinite. And you have to try to achieve that through sexiness, storytelling, and everything else that can be brought to bear.

Sketch by Antoine

Selling ideas… how do you work on the pitch?

It’s something we’ve gotten good at, though it’s still very uncomfortable. It doesn’t come naturally to us. Also, they’re more and more often in English, which makes it even more uncomfortable, for me in any case. I thought I was bilingual till I met Valentin.

V

It’s something of a necessary evil: on the one hand we want to show as much as we can to be convincing, on the other hand we don’t want to be boring or turn anybody off and present the client with something too precise that might stifle the project during its developmental phase.

Do you mainly get work through commissions or proposals?

To be honest, SG is doing well. And we can count on the fingers of one hand the number of times our proposals in a pitch have been successful. It’s pretty clear that we’re not sexy enough for that environment.

Which brings us back to presentation. How have you evolved?

Through practice. There are two types of situations: the first is when a client is hesitating between two studios; that means he’s chosen them both and considers both to be viable options for his project. You were competing against someone else, but you were approached because of what you do. I’m going to illustrate the other type of situation with a pitch from a famous watch brand: they obviously made a pre‑selection but asked us for a proposal. The winner was awarded the contract thanks to his idea, and not because of the identity of the studio, its aesthetic or values.

V

I could really lose myself in a vortex of work for a proposal even though it’s “only” a proposal which might not even be chosen. Nowadays we maintain critical distance to what and why we produce what we produce. We use our energy wisely and if we come up with good ideas that are rejected, we set them aside for a rainy day.

A

It used to be that by the time we got to the pitch the project was already done. We already had an insane concept and perfect 3D animation. Now we aim for efficiency; it’s entrepreneurial experience. And if in the pitch we show our client a super fine 3D visual it makes the client fickle and ungrateful afterward. It’s a beginner’s mistake to do that.

What would you have liked to know four years ago that might have helped you develop more quickly?

I’d say: “don’t snub Instagram!” Our growth rate increased dramatically once we got on Instagram. It kind of hurts to admit it, with all the snobbery that you can imagine, but it’s an extremely powerful tool. I don’t think I want to encourage the Antoine and Valentin of the past to go faster, because we’ve already gone very fast. I also don’t want to tell us to go slower because I’m super thrilled to be where we are today, even if it costs us to get here.

V

It was tough but we have no regrets. There might be a lot to say about our work pace.

A

Today what we’re trying to say to everyone, mainly the younger members of the team, is that the best solution is the one that yields the best results with the minimum amount of effort. To quote Bill Gates: “When choosing between two applicants I’m always going to pick the lazier of the two because he’s the one who’s going to take the fewest detours”. Which is a bit of entrepreneurial cynicism but also a real issue in terms of well-being that we find important. Nothing is worse than useless work. Also there’s another bit of advice that we could have given ourselves, which is that in terms of lawyers never hire buddies or people who’ve just gotten out of school. When you need a lawyer get a lawyer.

Sketch by Antoine

Could you give an example of situations in which you needed a lawyer?

We’d been around for less than a year when we got stiffed for the first time. Fifty thousand euros. Which at the time was a considerable sum for us. We were a small studio just starting out, so to save money we asked some buddies for help. But the lack of experience and communication problems since he was a buddy who was doing us a financial favour – all of that contributed to the failure of the endeavour. Then we approached some heavier people. It cost us nine grand and took a year and a half to get that 50 grand. Specifically, we learned that for certain amounts it’s worth the money you spend on lawyers to get the client who stiffed you to pay. So yes those guys in suits and ties are scary, working shifts that are even more insane than us designers, but no matter!

What strategies do you see as indispensable to you in the coming years?

We need to keep getting away from technique. That was our main selling point the first three years and is still the reason the telephone rings 50% of the time. Much has been said about 3D animation and CGI. We’re beyond that now; our value is our concepts; also I think I’d like to strike a better balance on our team in terms of seniors, middles, juniors, interns, etc. We test things out, and adjust. Not everybody has Didier Deschamps’ talent for creating a group dynamic. What we’re wondering is how to double our sales revenue without doubling the size of our agency.

Identity for Louis Vuitton’s new editorial content platform, 2019

How do you see and go about prospecting?

It’s a long process involving observation, curiosity, cultural and commercial appetite, magazines and Instagram or conversations with people around us. It happens through multiple coffees and meetings. It’s a practice that has almost become normal. The first year we were living off of the first ad agency that decided to give us work. We thought we would never need to do any prospecting: now we know different. If tomorrow we decided we wanted to work for the automotive industry we wouldn’t wait for the phone to ring: we would contact the brands.

Specifically, it’s monitoring, it’s information seeking?

If we say to ourselves that we want to work with Mercedes for example, that’s a big project: you’ve got to find the right person, the right channel. We shake the first branch of the tree which is our personal network. Then it’s a bit of Instagram, some LinkedIn and then emails and phone calls. In the beginning it was really us, me who did that stuff. Now we have someone to help us and we quickly realised how powerful that openness of spirit and curiosity is. People are very happy to meet with creative people who are full of ideas and more than that who present themselves as problem solvers. The first thing we attempt to communicate is not that we’re the best creative designers; it’s that we’re going to make their life easier. We put ourselves in their position, with empathy.

When you put yourself in other people’s shoes, when you try to understand how things flow within companies you realise that you’re not talking to Mercedes, you’re talking to the communications director of this or that division of Mercedes, with its own goals.

V

You can have several contacts within the same company and work completely differently in terms of creative freedom, the scale of the project, interactions. The nature of discussions changes depending on the person you’re dealing with. Many companies are very segmented, with a communication department, an architecture department, etc. And people from one department never communicate with people from the other department.

A

We worked twice with the same brand but with two different people, something no one actually realised. But to get back to prospecting, I don’t know if this was in 2018 or 2019… our accounts are very thorough and we realised that 70 % of our sales revenues had come out of prospecting. Once you become aware of that you forget your complexes and pick up the phone.

Augmented Sense in collaboration with Johanna Joskowska, 2020

What about the remaining 30%?

Sometimes serendipity takes over, you cold‑call and that’s more and more often the case with us, and then there’s past experience: it can come from the people I met at Céline, buddies, word of mouth… You go from prospecting to communicating about the entity that is SG. At first we didn’t really know what we wanted to say, or even do. I get the impression that we’re doing better now. SG is more than the sum of its parts. And there’s a phrase we’ve been repeating since the beginning: “We want to be everything for somebody, not something for everybody”.

Nina Ricci FW21

Was the (Auto)portrait event in 2018 part of a communication strategy?

Absolutely. It’s at the crossroads of many things. That’s why we have a lot of affection for this yearly event: a non‑commercial artistic project that’s fun and allows us to define our artistic discourse without it being diluted by a client; it also is a potential money‑maker in that it can create a buzz. Our very first year we invested 30,000 euros which at the time was not nothing. We could have invested a little less but it was too important for us. We had just barely set up a website and an Instagram account, and we weren’t prospecting. We put all our love into communicating. The first year it worked out really well. Our success was critical not financial. The second year it was a little more intimate, more anonymous but we got a lot of work out of it, with people who were more mature, and fewer cool kids.

V

And also, still today people call us talking about it.

A

This was Maison, so a kind of Maison manifesto. Maybe the project in itself was more commercial since there were fewer people at the exhibition and it was filled with people with money or a profession rather than students. I think we’ll try to do the next one at the crossroads of both worlds or get back to the cool kids. Because it’s fun to alternate.

(Auto)portrait, SG exhibition, 2018

There’s also, I imagine, the fact of getting media coverage.

Yes. We have a PR person whose name is David Giroire and who, like Willo Perron’s PR, is a little stressed by this. Because the press, to communicate, needs to be able to go from B to C. Creative design studios interest them of course less than a musician who is flogging his record. On top of that we don’t want to show our faces. We truly are a PR nightmare. So we’ve kind of given up on that: we take what we can get.

So Instagram is where it’s at?

Yes, absolutely. Instagram and the press don’t offer the same thing. One generates audience, the other an authoritative argument. There is the little Instagram blogger who’s going to get us a thousand subscribers in one day by writing about us because he already has 200,000. And there’s the magazine that’s a little serious which means that when you type in SG in Google you can see they interviewed us. Which reassures the client. Those are the two parts of the media that interest us. For visibility we depend on digital; for authority we need print.

When in your opinion does a creative entity communicate too much?

Is that even possible today, to communicate too much? (laughs)

A

The thing that pays off is consistency – whether on Instagram or for the YouTubers, etc – there is a bit of an overdose aspect to it, but it depends on how you want to be seen. If someone tells me he wants to be the cool kid and start trending I’ll tell him to spam on Instagram. If he tells me he wants to build a structure that 40 years from now will be financing his house in the country, I’m not going to tell him the same thing. I get the impression that on Instagram there are two major parts. The “work” part you often find in the posts that is the “respect the industrial chain” part: creating mood boards for example. And the part that attracts people and makes them spend time there, the “lifestyle” part: personal branding, little stories where you get to see the person’s office, that voyeuristic touch we all dig. On Eric Hu or Yorgo Tloupas’ pages you consume more lifestyle than artistic production. The work is seen as a kind of consequence of that lifestyle and so it’s the lifestyle that’s attractive, whether people admit it or not. If we played the personal branding game we might have more subscribers. I used to stupidly denigrate the fact of being admired by all those design kids in their French fashion schools, it’s stupid. Valentin is right: those young people are our future, our future colleagues, perhaps even our future clients.

How many employees do you currently have and how do you recruit?

Nine.

V

We believe we have yet to find the perfectly stable setup and we’re still trying to strike the right balance for each person. We’ve allowed ourselves a little leeway.

A

Once we find it our workload and projects will no longer be the same. So we’ll have to adjust to a new equation! It’s inconvenient to be so polymorphous. We no longer work with freelancers; we try to hire people on a permanent basis, if possible in office but also remotely, we were doing that even before the lockdown. We recruit 90% of them via Instagram. A job description, we meet them, we show them the agency. Many applicants don’t understand what we do, the causes and consequences of our creative jobs, to be honest. I remember the day we put out a Virgil Abloh ad, we got over 20 applicants… The first thing we do is to explain what’s going on. Then Valentin tortures them a little with technique. It all comes down to feeling. For a long time we wondered if we were looking first and foremost for people whose sensibility was similar to ours or if we were looking for technically proficient people with their own sensibility, and not necessarily similar to ours. We tend to choose the second option.

Evian Activate Movement campaign, with Virgil Abloh, 2020

What type of profile do you tend to recruit?

In a perfect world we would hire artists who share our aesthetic and vision but who are also technical virtuosos. Or, on the other side of the spectrum, pure technicians, animals that are completely deaf to creativity like the dudes who do the VFX in the Hollywood studios. We tend to choose technicians with a creative sensibility but not necessarily the same as ours. And it doubles my workload. My dream is to have creative back and forth with the whole team really understanding SG’s DNA. Which isn’t necessarily the case. The team is currently made up of folks who aren’t necessarily familiar with the graphics of fashion when it is in fact the hand that feeds us. I don’t yet know if this is an advantage or a disadvantage.

You mentioned that you have a person in charge of production and prospecting?

It’s a position that sort of invented itself. For a specific, very ambitious project we had called upon a super project director, a freelancer, and she confirmed what we had already intuitively understood. It really is quite a relief, and something we can’t do without.

V

It’s so indispensable that it makes my head spin to think of how we used to do things.

A

Sometimes you need to talk about the budget, you’ve to get away for an hour from the meeting and then you’ve got to give a plausible pitch. Otherwise it damages your credibility.

V

In terms of workload, we had come to a point where we were unable to do what SG is all about because we spent half our time answering emails.

A

There’s a finite amount of decisions you can make per day. After dressing in the morning, eating lunch, answering emails, and taking meetings, by the time you’re called upon to make a creative decision you’re wiped out.

What is your current take on the creative sector?

I get the impression that entrepreneurship is increasingly important; there’s also a kind of atomisation, since you’re contacted by smaller and smaller entities. The agency model seems to be disappearing. Brands and designers are more and more often in direct contact. Many studios have been set up, I don’t know if it’s a consequence of this. Online, all our interns present themselves as a studio, by simply adding “studio” in front of their name. Also, two or three years before the lockdown the archetype of the fashion show was beginning to appear shameful. The lockdown shook everything up; certain brands were brave enough to stop doing shows; others found different ways to keep on doing them. And then there are those who are left out and want one thing only: to get back to packing 600 people per square foot while spending 10 millions for 10 minutes, with the ecological fallout that that implies. It’s kind of amazing. Also, I think the lockdown showed how essential art is to us – whether used industrially, or the Fine Arts, film or music. Art plays a central role in our lives. It’s crucial in fact. Imagine a lockdown without movies, music, cartoons, graphic novels, without any visual or aural stimuli, it would be catastrophic. I hope this realisation leads people to have a little more respect for our creative professions and come Christmas time, the art school students won’t be seated at the end of the table trying to justify themselves to their family who sees them as utopian eccentrics!

Télévision magazine, Fashion editorial series, 2018

Télévision magazine, Fashion editorial series, 2018

What is your relationship to innovation and how does it impact the profession?

I have a singular relationship to technique. I know I’m not good at it, and I don’t want to go down that rabbit hole. When I was a teenager I lived next to Neil Poulton, the industrial designer known for the orange Lacie exterior hard drive. He told me not to worry, that lots of people knew how to use soft 3D, but that few knew what to do with it. I’ve often thought of that conversation, clinging to it like a clam to a rock, for reassurance. At the office we only have technical virtuosos. Which means I have the luxury of not having to think about it. I hope our productions are not 3D gimmicks; we use 3D animation because for the moment it’s the best tool with which to produce the visuals we want to produce. And yet I have noticed that my teams spend their lives in a race against time, worried they’re being outdistanced by technique. Valentin is in a way our pathfinder, guiding us with his sceptre towards the new. Naturally I wonder about the end of it all. I say to myself that there’s going to come a time when the CGI aesthetic is going to level off. Soon the entire aesthetic we’re producing will become something future generations are going to wax nostalgic about, so I believe people are going to return to the roll of film and VHS. I hope that our creative references will come back and that we in the meantime will have moved on to other things and that we’ll be on the cutting edge of other stuff!

V

We’re currently standardising the use of our tools in the fields we use them in. In the movies nowadays most of the special effects are invisible. One day computer‑generated images will be as common in fashion, the automotive industry, and pack shot products as it is in the movies. We must fight against our own tools to avoid being inhibited by the aesthetic they sometimes end up dictating (this is in truth a battle that not enough CGI artists are waging). And of course with time these tools will become more accessible, less expensive, simpler, and smarter.

Studios such as yours have put an end to the domination of production companies with sophisticated technicians and equipment. Now they’re looking to small studios for creative solutions. Have you been approached by anyone?

Yes, we were approached, they wanted an equity stake, and we thought about it for a long time before deciding to decline, though we were very flattered. Our biggest worry was wondering why someone would want to buy SG, and we couldn’t come up with an answer. It’s about our freedom in terms of creativity and decision‑making; that’s why we declined the offer.

V

After all this company is our baby and if everything works out, our only company forever. So we’re very identity‑oriented: the idea of selling hasn’t entered our mind.

Do you think equity fundraising might guarantee your creative independence while bringing bigger budgets?

To create a studio such as SG you need no investment other than time. For people who are less attracted to entrepreneurship and corporate management – the truly business side of a creative design studio – it might be a good idea to join forces with someone, to get trained and team up with a business angel. As for us, when we were approached we had the impression that someone was coming to reap the benefits of the three years we had spent working our asses off.

Some of your objects have been produced by Theoreme. If you decide one day to launch an object collection, could that be the type of entrepreneurial project that would necessitate equity fundraising?

I know through family experience in this field that making money with objects is not easy and that’s euphemism. Very few people succeed. As for us, objects are more for fun and amusement, limited edition pieces that don’t cost that much. We would probably finance that ourselves.

The Services Généraux’s Contenu Vase (edited by Theoreme), in their Maison Manifesto film, 2019

Could you imagine investing in other studios, other projects or brands? Through SG or as individual shareholders?

Individually, yes. It’s already the case. As for SG doing it, I’m not sure. It doesn’t seem very natural.

V

It’s in keeping with the things we do for free. These days we work fairly regularly on artistic collaborations or brand‑led charity endeavours where we didn’t charge anything since it would have taken money away from the association we were supposed to benefit. If we were ever asked to participate in a creative project with a creative and financial investment, if it was attractive enough I think we would do it. Helping people get started is a good thing. If the possibility presents itself, why not.

sketches by Antoine

If you could exercise your profession at another time in history?

There’s a famous sentence bouncing around the internet: “I miss my pre‑internet brain”. I’ve practically never had a pre‑internet brain. To do my job without internet, I can’t even begin to imagine what that would be like. So for Valentin…

V

It would be strictly impossible. Quite simply. There are no tools in existence as radically geared toward creativity as internet, at least as far as I’ve been able to see, at any other time in history. The emergence of internet and mainly of computerisation in general is really the emergence of an entire category of society that is devoted to creativity. It’s really unparalleled as far as I know. Maybe the advent of photography or cinema, and even that.

A

I really like the question though, because it injects humility into my artistic director job. It’s really important in our profession where our role is principally to summarise and produce creative scenarios. We realised that if we’re able to present such elegant overviews it’s thanks to the mass of data we have at our fingertips. It’s like AI: the more data you give it the more relevant the answer you get. All artistic directors nowadays are incredibly spoiled by the corpus of references at their disposal. That definitely wasn’t the case in the 1970s. It’s the gift and the curse. You have an enormous amount of pressure on you to come up with something original even though it’s almost impossible and that all that remains is intertextuality. You just have to grieve the loss of originality.

Is there a book that helped you better grasp your profession?

Absolutely without any connection to what we’ve been talking about, my favourite book is Seveneves by Neal Stephenson. It’s hardcore sci‑fi set in the future and is, I believe, perfectly plausible from a technical point of view.

Any advice for someone starting out now?

I’m going to talk about what’s more my field, which is the mad dash to technology and the desire to use the latest gear, the latest technique, etc. There are people who are always going to want the latest plug‑in, the latest tool. I used to be like that at one time, I was obsessed with photogrammetry; I wanted us to use it everywhere, I thought it was going to revolutionise our industry. And in the end, though it’s practical from time to time, mostly we don’t use it. Most of all we need to improve on what we know and find the method we’re going to use to achieve that. “This one because I know it and feel comfortable with it”, is really the right answer.

A

I can say what we say: “work for free not for cheap”. This is often the case! Because we really make the distinction between people who literally monetise visibility, and when it’s worth donating your time to an interesting project. To put it somewhat cynically: if you work for cheap, the client immediately forgets your generosity, he just wants the service he paid for. Regardless of the price. But if you do it for free he owes you and therefore you reduce his feedback by 50% and the project will be funner. My second piece of advice is a little mean, and snobby: people work less than they think and less than they say they do. Time spent working in the office is not really when you create value. People really have to learn to separate labour from value. The added value in our work, if you’re creative, is when you’re taking a shower or on the can or in the subway or on your bike. It has nothing to do with the hours spent at the office. To perform well your brain has to be on all the time, including when you’re out of office. And the idea of working under deadlines which is something you often hear about in creative jobs is exaggerated and out of date. Just because you finish working at 11 o’clock at night doesn’t mean that you work a lot. In Japan you spend your life in the office and sometimes even sleep there; and yet France is ahead of Japan in terms of productivity, with shorter work weeks. One last bit of advice. At school in France we’re spoiled, everyone pays us a lot of attention. But nobody is expecting us once we graduate. There really is a huge gulf between student and professional life. My advice to anyone who wants to work in the creative industry, either as an employee or entrepreneur is to begin some light prospecting before you graduate so you can get an idea of what’s going on.

Ropes, 2021