Hello, Valerio. Could you please introduce yourself?

Hi, I’m Valerio Tamagnini, co-founder of Studio Blanco. Sara and I established the agency about 18 years ago. We’re located in Reggio Emilia, a small town situated between Milan and Bologna in Northern Italy.

Studio Blanco’s studio in Reggio Emilia

Studio Blanco’s studio in Reggio Emilia

How would you describe your current operations? The name Studio Blanco suggests a studio, yet you refer to it as an agency. Can you elaborate on that?

[Laughs] Sure, it’s interesting because we did start as a small studio—just Sara and me. For the first half of our existence, we operated as a typical studio, with a team of no more than five or six people. As time passed, growth happened organically, it wasn’t exactly planned. This growth gave us opportunities to expand our capabilities beyond just the finishing touches of a project. We began engaging in strategic planning and executing tasks in areas traditionally beyond the scope of graphic designers, such as event planning and website completion. Consequently, we had to scale up our internal structure and team size. So now, we find ourselves in a hybrid space, straddling the line between a studio and an agency. With a team of almost 15, we could be seen as a boutique agency or a large studio—it really depends on how you look at it.

Studio Blanco co-founders Sara and Valerio

Let’s circle back to the integration of strategy into your work later. For now, what’s your current state of mind?

I’m doing really well, especially because it’s Friday. But beyond that, we have some exciting projects in the pipeline. I’m also looking forward to traveling soon, which is always a plus. Living in Reggio Emilia, with its tranquility and fantastic food, is great, but I also crave the energy that comes from meeting new people and visiting new places. So, I’m quite excited about the upcoming few weeks.

Can you share what initially drew you to graphic design and art direction?

Interestingly, I’m not a graphic designer by trade. Before starting Studio Blanco, I organised events, and the studio was initially supposed to be an event agency. Sara, who is both my business and life partner, was the graphic designer. She freelanced here and there, looking at art direction primarily as the visual side, while I had a different approach to art direction, focusing more on concepts, communication strategy, and overseeing execution. Our different approaches have been a cornerstone of our work. While I deal with the rational aspects of a project, Sara brings her visual expertise to the table. Over the years, I’ve become more involved in the creative process, but I leave the detailed and technical creative decisions to her.

When you founded Studio Blanco, did you have a strategic development plan, or was the growth organic?

In the very beginning, there wasn’t a clear vision. I handled the contacts and opportunities, and Sara had a keen eye for design. We realised early on that combining our skills was more effective than working separately. Although the path wasn’t clear, the diversity of our skills—her visual design expertise and my strategic thinking—gave Studio Blanco a unique strength. It’s challenging to build an agency with a graphic designer’s mindset because it requires a broader vision that includes business development and networking. Our ambition was to create a distinctive voice from Reggio Emilia, to work with people we admired. This has been a lengthy process, but it has involved engaging in self-initiated projects like organising concerts, exhibitions, and producing books under the Studio Blanco name. These weren’t just branding exercises; they were passions of ours that connected us with artists and a larger world. Our small-town origins never limited us; instead, they motivated us to reach out and collaborate with admired artists, and surprisingly, many of them were open to it.

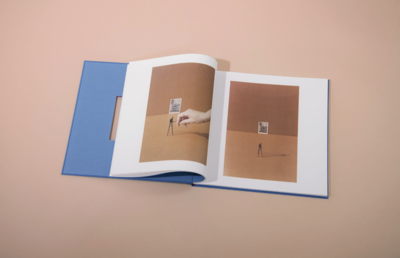

Luigi Ghirri - The Marazzi Years

Luigi Ghirri - The Marazzi Years

Your stories about the small town resonate quite a bit, suggesting that settling in Reggio Emilia was a deliberate choice. Was there ever a point when you considered moving away?

It’s quite amusing, actually. There’s a newfound appreciation for our small-town origins, which has become part of our narrative—how we’ve established ourselves starting from Reggio Emilia. But the truth is, this wasn’t a calculated move. Originally, I had aspirations of relocating to Milan or Paris. About thirteen years ago, which was several years after we started our studio, we were seriously looking at spaces in Milan and were on the verge of leasing one. Around the same time, Sara became pregnant, which made us pause and think that it might not be the ideal time for such a big move. Within that year, our son Lucio was born, and coincidentally, the high-speed train service began operating between Reggio Emilia and Milan, cutting the travel time to just 45 or 50 minutes. This development made us somewhat complacent, as the ease of commuting significantly bridged the gap between living in a small town and working in the city.

To be clear, I don’t exclusively advocate for small-town life or criticise city living. What works for us is the convenience that comes with our location—we enjoy short commutes and a more relaxed pace of life. For instance, I walk to work and used to walk my son to school. This simplicity wouldn’t be as feasible in a bigger city.

Moreover, starting a studio in Reggio Emilia, a city within one of Italy’s wealthier regions, definitely had its advantages compared to, say, a smaller town in Sicily or other parts of Italy. From the get-go, we had certain opportunities that stemmed from being surrounded by industries. So, it wasn’t just a stroke of good fortune or having a good idea; we were also strategic in tapping into an existing market and elevating our services beyond just local clients. We didn’t settle for a comfortable niche; we pushed ourselves beyond that.

When Studio Blanco was first established, what were your sources of inspiration?

Initially, M/M Paris was something of an idol for us—representing a pinnacle of creativity and visual innovation. However, it wasn’t long before we realized their artistic approach didn’t quite align with our own. They embody the artist role in ways we do not. Sara and I don’t see ourselves as artists; we’re more pragmatic, running an agency that serves clients while also choosing projects that are meaningful to us and our community. Working with artists like M/M Paris is always a pleasure, but our role is different. My background in events and DJing, albeit not at a high level, influenced my approach. In DJing, you curate and mix to create an ambience. It’s similar with our agency; we curate elements to craft a successful project.

Prada Raffia Project

Prada Raffia Project

Working as a couple in the creative industry is quite particular. How has this dynamic been for you and how has it evolved?

To be frank, partnering professionally with your spouse is something I wouldn’t recommend. It’s challenging. Looking back, I see distinct phases in our partnership. In the early days, our small team was laser-focused. We’d start late in the morning but often worked until midnight, pouring ourselves into building Studio Blanco and investing extra hours in passion projects. As time passed, especially before our son was born, we faced difficulties separating work life from personal life. After years of constant close quarters and extended work discussions at home, we contemplated a change.

Our son’s arrival marked a new chapter. Parenting brought its own set of challenges, but it also imposed boundaries that helped us compartmentalise our lives—beneficial in many ways. Nowadays, with over a decade of experience, our studio life is more structured, generally from early morning to the evening, a routine partly shaped by our responsibilities as parents. This change was healthy, studio is operating from 9 AM to 6-7 PM, though I typically start my day earlier, around 8 to 8:30 AM.

Maison Margiela The MM Code

Maison Margiela The MM Code

Is it because you have a child now? I share your routine; I arrive early as well. What intrigues me is how creatives at the cusp of parenthood experience reorganisation. For them, this transition seems to come naturally. Is that what you’re finding?

Yes, the initial phase was tough. I leaned heavily on Sara’s contribution, and with Lucio’s arrival, her studio time diminished significantly for about a year, challenging us. That time compelled us to recalibrate, cultivating key individuals within the studio beyond just the two of us. Eventually, this restructuring made us stronger, not solely dependent on one another. Establishing clear boundaries between work and family life became easier, which in turn fostered a healthier environment. While workplace tensions with Sara might still spill over at home, they’re less impactful now. The priority becomes family, and the work-related issues become secondary.

Given your background in events and DJing, where creative work wasn’t your initial focus, you appeared to pivot strategically to development and client projects. Have you allowed time for side projects that offer something different? What were your strategic inspirations?

Looking back, our trajectory is clear, although it wasn’t so in the midst of it all. Our priority was to attract engaging endeavours to our town and beyond, as Reggio Emilia alone didn’t suffice for our ambitions. I began organising events at 16, starting with a punk hardcore festival, learning the value of self-initiative and self-sufficiency early on. Rather than complaining about the lack of offerings, I sought to create them—whether it was inviting artists or setting up exhibitions. In the end the goal was not to meticulously plan for financial gain but to find a balance that allowed commercial work to subsidise our artistic aspirations while maintaining the ‘Do it yourself’ ethos.

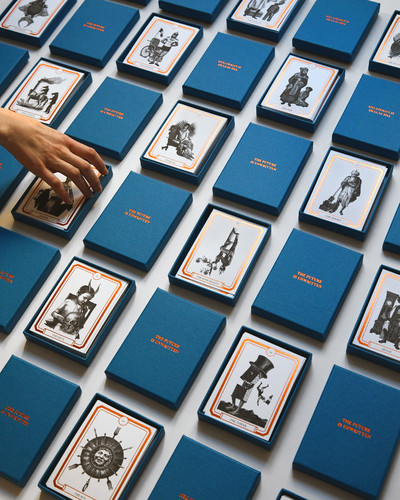

The Future is Unwritten tarots set

Your do-it-yourself ethos reminds me of another art director we interviewed, Benjamin Grillon, who also has a musical background as a bass player. He referred to the band Fugazi, which I find quite fascinating.

Indeed, they are grand.

There’s this documentary about Fugazi that he recommended. It’s impressive how they established their identity and their label. It’s a compelling example of how creative output can be channeled into a brand or product that you offer to the public.

Absolutely. My initial influences were quite similar, including Fugazi and even some straight edge bands. I grew up surrounded by my father’s collection of comics and magazines. Since the age of four or five, I was immersed in a world of books, comics, and magazines, though I was more captivated by music magazines than fashion ones—I had no interest in Vogue, but publications like iD, The Face, The New Musical Express, and The Melody Maker caught my attention. Around the age of ten, I was deeply influenced by the pop culture of the times. Having access to so many magazines sparked my interest, and when I was a bit older, I joined a group of friends who were involved in music. They were older and had started their own fanzines, which inspired me to start one myself. I published just two issues before moving on to another one. This hands-on approach of creating content without compromise—writing on the computer, using glue for collages—was my foray into fanzine creation, not as a graphic designer but using collage to craft these works. That ethic was particularly inspiring to me.

Church’s Web site

Church’s Web site

These are strong creative print references.

Absolutely, I have a valuable collection of fanzines, including ones from America. The culture was unique; we used to trade fanzines rather than buying and selling them. We’d barter based on quality and production cost, like exchanging five of mine for two of a higher quality. It was a small, closely-knit community. I remember trading with Nico Vascellari, who’s quite renowned now. We’d exchange mail and various items. It was an exciting time where anything felt possible, even though I wasn’t wealthy. Sara and I come from humble backgrounds. My parents, though, supported my endeavours, like the time I organised this festival at 16. They even covered the costs for flyers when I forgot about promotion, leading to a small financial loss. That experience taught me the importance of marketing for events.

Walter Albini website

Walter Albini website

Your experiences tie into our next topic perfectly. Out of curiosity, have you seen the “Get Back” documentary? It features The Beatles during a highly creative period, a year before they split, as they had one month to produce an album. Directed by Peter Jackson of Lord of the Rings, it’s beautifully colour-graded across three episodes, each three hours long. It provides a deep look into the band’s dynamics and creative process. It’s fascinating to see how they manage roles, with McCartney being surprisingly pleasant and organised. It’s an insightful piece, not just about management but also their genius and dedication.

On the topic of record labels, they were a key reference for me in the punk hardcore scene. Record labels often went beyond just music; they organised concerts, ran stores, and sometimes involved in artistic activities. They were more like labs than mere businesses. Around 2005, when I started my studio, I was inspired by Trevor Jackson—a graphic designer, musician, and the owner of the Output label, known for its incredible graphic design. He was involved in multiple creative fields, which I found very admirable.

In terms of strategic development for Studio Blanco, what do you consider essential nowadays? How do you approach strategy and future planning? Are you in charge of that, and how does Sara fit into the picture?

The strategic side largely falls to me. Sara tends to concentrate on the visual aspects, though we do discuss strategy occasionally. She trusts my judgment on what could be beneficial for us. We have a team for client management; for instance, Cristina has been with us for 7-8 years and is someone I can seek advice from. Looking ahead, we’ve grown significantly in the past 6 years, but I’m not looking to expand much more. We’re at a juncture between being a studio and a small agency, and I value being closely involved in our projects rather than just managing client relations and internal issues, which can become challenging with a larger team. We’ve also acquired a new space in Milan to serve as a small outpost from January, while maintaining our main headquarters here.

In terms of vision, we’ve reached a satisfactory level this past year. I appreciate that our work isn’t just about visual appeal but also about strategic input. Clients seek our perspective on strategy and decision-making, which is valuable beyond the visual elements. At 43, both Sara and I must consider our relevance in the visual field. While some designers remain influential into their 50s, others do not, and it’s not always graceful. I aim to maintain relevance not just visually but by adding value through our experience and knowledge of the process.

Working with a younger team, often under thirty, presents a generational gap—sometimes up to 18 years between myself and other team members—which can be stimulating. I offer them well-known references that are new to them, and conversely, they introduce me to artists I’m unfamiliar with, akin to learning from my son.

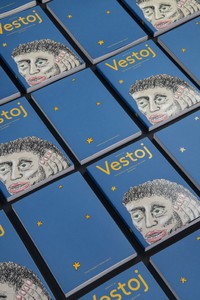

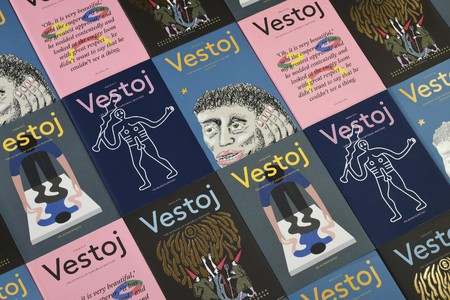

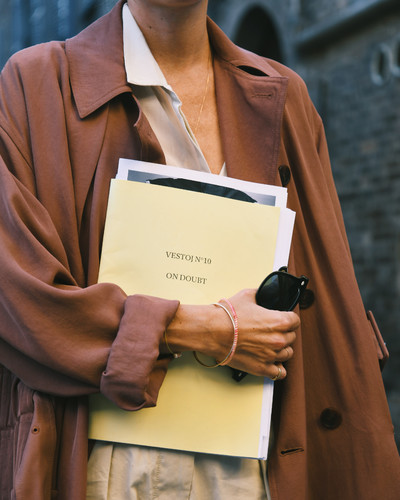

Vestoj magazine

Vestoj magazine

Vestoj magazine

It’s fascinating because your studio isn’t named after you “Sara and Valerio” or simply called ‘the agency’; it’s Studio Blanco. You have a distinct visual style that brings coherence to your work. Do you believe young talent can maintain this momentum in the future?

Absolutely, that was crucial to me from the start. Take Margiela as an example; he was an intriguing reference for us. We weren’t keen on being the public face of Studio Blanco. In today’s social media era, it’s rare to find many images of us. We often say no to our social media manager when she suggests promotional ideas that we prefer to avoid. We prefer to focus on the work itself rather than on personal fame. Our approach has evolved, but the essence of Studio Blanco remains. We aim to bring people together to follow a cultural, ethical, and aesthetic journey while incorporating their perspectives. I’m open to the idea that Studio Blanco might continue even without our direct involvement in the future. That would indeed be an interesting challenge.

Sketch by Studio Blanco

There are a few instances like this already, and I believe we’ll see more in the future, but that’s just my personal guess.

I agree, particularly considering our earlier discussion about DJs. Just as DJing evolved since the ’70s, so has graphic design. It’s relatively young as a profession, and a bit of uncertainty can be healthy. If a design studio or creative agency can establish a strong visual language and reputation, it might endure changes in personnel, similar to how fashion brands evolve with different designers while maintaining their legacy.

I recall Dumbar as an example. There’s no longer Dumbar; Lisa Einebeis, who we interviewed and was once an intern there, is now the creative director. It’s part of a group now. We see movements like this among independent studios that have unique goals.

Right, KesselsKramer is another example. Erik left the company years ago…

And it’s interesting that both are Dutch. There’s significant activity in the Dutch creative industry, like how Random Studio acquired Bonsoir Paris and transitioned to Random Paris. The Dutch are quite entrepreneurial in the creative sectors. So, how do you handle business development and what are your next steps?

In terms of our agency, we have an unconventional approach to client acquisition. We don’t have a dedicated new business manager, which has its pros and cons. We’ve been fortunate to build our reputation and receive opportunities organically. I sometimes wonder if we need a business development person, but that role’s traditional methods of reaching out and presenting don’t align with our style. Instead, we’ve adopted more subtle, organic ways of networking. For eight years, for instance, we’ve hosted dinners with chefs from around the world, inviting a mix of paying guests and non-paying guests. These events have been excellent for meeting new people and fostering relationships. We also arrange divisions, concerts, and keep parts of the books we publish to send to people we want to connect with. These strategies suit us better than the direct approach of soliciting business. On a day-to-day basis, Cristina and I, along with others in the studio, manage client relations. When clients approach us with potential projects, we then proceed with analysis and meetings.

Vestoj magazine

Have you considered getting an agent or representation, given the changing landscape for agencies?

Yes, I’ve thought about it, particularly for cities like Paris or London. Our multifaceted identity has made it a challenge to find the right fit. We started primarily in fashion as art directors, where having an agent is common, but being both a studio and an agency complicates things. Although I admire some agencies and would like to be represented by them, it’s difficult for them to categorise us since we do more than just art direction. I’m open to the idea if the right opportunity and person come along.

It’s a complex issue for agencies and art directors to be represented, considering they often manage business and project development in-house.

For artists or designers, having an agent can be beneficial because it allows them to concentrate on their creative work, leaving the business dealings to someone else. However, an agent needs to sell a specific style or package, which works well for illustrators with a distinct style. When you have a broader, integrated approach, like we do, it’s more complicated. Studios like M/M Paris or OK-RM might find having an agent more suitable due to their size and distinct identities.

We interviewed OK-RM; they’re about 5 to 8 people, depending on the projects.

Right, so for smaller studios with a strong voice, an agent can be perfect. For larger ones, it’s more variable. Although we’ve been fortunate with a good amount of projects, I’m still open to discussing possibilities with interesting agents when the time and opportunity are right.

You mentioned the challenges in your communication strategy, considering you have diverse activities. How do you manage communication across your platforms like your website, Instagram, and events like dinners?

Balancing the various aspects of what we do can be challenging to communicate externally. Events like dinners or concerts may confuse people who associate us with other services. This confusion can be positive if it piques interest, allowing us to explain our core activities. Our website serves as a straightforward, corporate presentation, whereas Instagram allows us to be more experimental, engaging people in a less formal manner. Most people first interact with us on Instagram, then move to the website for more focused information. While the website aims to be reassuring and exciting, Instagram is a space for us to play and experiment, even if it means posting less frequently.

Studio Blanco’s studio in Reggio Emilia

I understand the dilemma. We also adopted a similar approach. Unsurprisingly, a portrait we posted was our most-liked post on Instagram.

Posts about our physical studio space or those that include people tend to attract a lot of attention. We recently had to do a photoshoot for a magazine, which required portraits. Although I’m not as strict about privacy as, say, Martin Margiela, our public image still significantly impacts engagement, as shown when pictures of me and Sara with the Monocle Award received a lot of excitement.

Can you tell me about the current size of your team? How many people do you have working at the studio in Milan or elsewhere?

Right now, in Milan, although we’re set to officially open in January, there are already people working remotely from there. In total, our team is almost 15 people strong.

How do you handle managing your team? Where did you acquire these skills? It seems like your experience with organising punk hardcore festival must have involved managing challenging situations too.

I’m not sure if I ever formally ‘learned’ management. I tend to adopt a practical, ‘do-it-yourself’ attitude. I dive in, do the work, and learn from my mistakes. This approach has been enlightening, especially as we evolve. For instance, we used to operate with a much smaller team and I often wonder how we managed back then. We’ve made technological upgrades, like moving from a physical server to using Dropbox for file sharing, which supports both in-studio and remote work. It’s astonishing to think that just five years ago we relied on a physical server. Regarding team management, we now have weekly meetings and bi-monthly one-on-one discussions to address opportunities, issues, and so forth. Previously, we didn’t have such structures in place. It’s been a process of learning and adapting. With a team of ten or fewer, the dynamic is one thing, but beyond ten, it changes significantly. This is also why I’m hesitant to expand the team much more. We’ve even started a separate entity focused on e-commerce to manage growth better. Handling a large team can become quite complex.

Sketch by Studio Blanco

So there are 15 people at Studio Blanco, and then there’s this other business entity on the side?

Yes, the side entity is just me, the founder, and another colleague, making it three of us. It works in tandem with Studio Blanco and is beginning to take on its own clients as well.

Are you a partner in this side business, or is there someone else involved?

It’s me, Sara, our former CTO who is our technical partner, and a developer. It’s a venture that’s focused on technology, e-commerce, and related areas.

That sounds like a very strategic and business-savvy expansion.

Yes, digital has been a crucial aspect for us from the very beginning. When we started, digital wasn’t highly regarded in the fashion and design industries. Most art directors, especially those focused on fashion, prioritised shooting campaigns and largely ignored the digital translation of their work. It was somewhat comical at times—I recall instances where well-known art directors would give us screen instructions in centimetres, which was quite out of touch. There was a definite gap that we noticed. Our team, being younger and more attuned to digital media, saw an opportunity. It was around 2010, we were in our thirties, and many of the established art directors were a decade or more older. So, we began creating small websites and special digital projects for various brands, starting with Max Mara, and eventually working with names from the Kering group, Ferragamo, etc. The traditional approach from major art directors was still very print-focused, while the digital aspect was often overlooked and messy.

We gained recognition for filling this digital void, taking on special projects that others weren’t willing or able to execute at the time. The traditional ad agencies operated more like engineering firms, treating a luxury brand like Prada the same as any other retail client, focusing on blocks and pixels rather than the design integrity. So, we capitalised on this gap. Our approach was holistic; we handled print, digital, and events with equal interest and expertise. Sara was even programming in Flash, which now is no longer used. As a small team, we managed the entire creative process.

Over the years, brands would sometimes ask us to develop a website from concept and design to the actual development, while other times they would take over after the design phase. However, when they did, the results often fell short, forcing us to step in and make corrections. It became apparent that we needed to have our own development team to ensure quality and integration, leading us to start a smaller venture focused on development and e-commerce. This allowed us to offer more comprehensive services and maintain control over the process, accepting responsibility for our work.

Vestoj magazine

You’re clearly among those designers and art directors who foresaw the need for digital integration in the industry. You mentioned a significant technical gap that existed with older art directors. Which concerns do you have about potential gaps in the future, such as keeping up with new technologies? How do you stay current with emerging trends like artificial intelligence or the metaverse, which, while seemingly on the decline, might still hold potential in a new form? Do you find that collaborating with younger team members helps in this regard?

Collaborating with younger individuals is certainly beneficial. I can’t claim it’s the definitive solution, but it’s a positive approach. I appreciate that there’s an element of uncertainty in it, which I find intriguing. When I was beginning my career, I probably had my grievances about art directors in their 40s or 50s, and now, it’s likely that newcomers will soon critique us for not keeping up with the times. This idea keeps me on my toes and pushes us to continuously evolve by integrating different languages and elements into our work. Although I’m sometimes experimenting with artificial intelligence, I don’t have all the answers. In our studio, others, including Sara, are more involved with AI than I am. This uncertainty is compelling because it spurs us into action, whether that’s exploring new technologies or diversifying our client projects to keep things interesting. Regarding the metaverse, we weren’t particularly drawn to it. It reminds me of the hype around Second Life, where I was hesitant to dive in, and I feel similarly about the metaverse despite its potential growth and investment.

Personally, I find NFTs interesting as they could revolutionise fashion editorials for CGI artists. There’s something compelling about digital images and photography. However, I’m wary of the metaverse. In the past, fashion and luxury brands were cautious with new media, like the internet and social media. They waited to develop the right image before engaging. Yet, they’ve rushed into the metaverse and NFTs, indicating a significant shift in their approach.

It’s true that big brands like Gucci and Armani, with budgets for new initiatives, can afford to experiment in spaces like Second Life. But as I’m not an expert, I prefer to observe and see how these ventures pan out before forming an opinion. While NFTs have piqued our interest due to the shifts they represent in photography and art markets, we try to maintain focus amidst the chaos of our work. Venturing into the metaverse seemed too far a stretch, especially since it would add another layer of complexity to what we already do.

Prada Raffia Project

Onto more trivial questions now. If you could do another job at another time, another historical era, what would it be and when ?

Another job? I don’t know, but I’m really fascinated by the Italian situation in the 50s and 60s, a time when the creativity and vision of the industry were really different. Nevertheless, I’m not one to dwell on nostalgia and regrets, so I strive to make the most of the present and do my best here and now.

Are there books which have helped you?

More than books, I suppose magazines (and music) played an important role in my education. They provided energy and depicted situations that were beyond my immediate perspective, offering glimpses from all over the world.

An artist or a person whose work has helped you in terms of development?

More than a person, it was a club. Maffia Club, based in Reggio Emilia, played a pivotal role in the Italian electronic scene between the 90s and the early 2000s. I initially attended as a guest, and I eventually began organizing events there. The atmosphere, the people, and their vision instilled in me the “you can dream it, you can do it” approach.

What’s your advice for creative talents starting a studio nowadays ?

Stay true to what you like and where you come from. Be distinctive. And don’t forget about the money, because there are wolves out there…